New World Quarantine Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Next>>

New World Quarantine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 6

History of Yellow Fever

Trying to determine which epidemics were yellow fever before and during the golden age of pirates presents an interesting problem

Yellow Fever Characteristics Identified by Henry Carter

- it is difficult to distinguish it from

other illnesses found in the New World because of the way these illnesses were described. Unlike smallpox, which was familiar due to its long history in the Old World, yellow fever was a disease neither well-understood nor properly distinguished from a variety of other illnesses which were accompanied by many similar symptoms. In tracing the history of the virus, retired US Assistant Surgeon-General Henry Rose Carter gives quite a bit of insight into the problem of differentiating yellow fever from other illnesses during the European exploration of the western hemisphere. As he explains, part of the problem is that "earlier accounts, up to near the end of the seventeenth century, are none of them by physicians, and even when a description is given one is rarely able by it to recognize the malady with any certainty."1

Many of the illnesses contracted are described by their symptoms alone, sometimes being given a name which has little correlation to what we call them today. In his effort to distinguish yellow fever from some of the other illness, Carter listed eight characteristics of the illness which can be seen at right. Some of the items in his list are a bit questionable (he suggested that African Americans were less likely to succumb to yellow fever for example), but the list is still helpful when attempting to disentangle yellow fever from mass of vaguely-described and often lumped-together illnesses like dysentery, influenza, malaria, typhus, scurvy and spirochetal diseases. Carter goes through each of these illnesses in some detail, pointing out differing or missing symptoms between them and yellow fever in his book.2

1 Henry Rose Carter, Yellow Fever - An Epidemiological and Historical Study of Its Place of Origin, 1931, p. 49; 2 Such an examination is unnecessary for understanding yellow fever during the golden age of piracy. For an in depth look at the differences between these diseases and yellow fever, see Carter, pp. 53-75

Yellow Fever in the New World Before 1647?

Like the origins of its name, the historical origins of yellow fever are murky. Writing in 1955, Dr. Pedro Nogueira said,

Artist: Ridolfo Ghirlandaio - Christopher Columbus, (16th Century)

"The first accurate description of yellow fever seems to be the one written in the year 1495, after the battle known as Vega Real or Santo Cerro, fought by Columbus in Hispaniola against the Indians."1 In his Historie, Ferdinand Columbus explained that the illness contracted by his father "was something between a pestilential fever and a drowsiness or supreme stupor which totally deprived him of all his forces and senses, so that he was believed to be dying and none believed he would last out the day."2 While the symptoms could be indicative of yellow fever, there is not nearly enough detail to distinguish it from a number of other fevers the explorer may have contracted. In fact, Henry Rose Carter suggests that the accounts given by the men returning to Spain of this illness "indicate malaria, not yellow fever."3

Nogueira goes on to point to several other early Spanish expeditions where he thinks yellow fever may have played a role, including those of "[Nicolás de] Ovando, [Serrano and Diego] Nicueza, [Alonso de] Hojeda et al... Santo Domingo was scourged in 1495 and later in 1554, 1560, 1567, 1580, 1583 and 1588... According to the Spanish writers Hernandez Morejon and Hurtado de Mendoza, Cadiz and Malaga were visited in 1507 and 1582."4 However, it is not at all clear that these attributions are correct.

Artist: after J. Aurego

People Suffering During a Yellow Fever Outbreak (1821)

Writing decades before Nogueira, Carter warned that many febrile illnesses were "simply classed as 'una peste', 'una fiebre pestilencial' etc. These are the most common terms used, although 'la modorra,' (the lethargy, the stupor, the sleepiness)... was common in early Spanish writing, and evidently covered more than one disease. "El contagio" is also used, implying the opinion that the disease in question was communicable, and 'la epidemia,' implying its high prevalence."5 Carter provides an extensive examination of the each of the Spanish sources in his book, explaining why they are unlikely to have been yellow fever. While interesting and, in many ways, enlightening in understanding the problems with Nogueira's attributions, it is beyond the scope of this article.6 As Modern authors S. L. Kotar and J. E. Gessler suggest, "Symptoms of yellow fever, although thoroughly described in the medical and popular print of the time, were nonspecific, leading to confusion over precise diagnosis. Even today, clinical diagnosis ...ends only by advanced laboratory identification. It is therefore impossible, at present, to state with certainty the time of its first appearance."7

As a result, although some historians suggest yellow fever was always endemic to the Americas, most researchers today believe that yellow fever did not originate there. They instead suggest that it arrived with the importation of slaves combined with the establishment of sugar plantations in the 17th century. Using viral samples taken from a number of different places and years from the twentieth century, molecular biologists determined that "isolates [samples] from West Africa are most closely related to those from the Americas" with the data suggesting the virus arrived in the New World "within the last three to four centuries [providing] compelling support for an initial introduction during the period of the slave trade and first contact between the two continents."8

1 Dr. Pedro Nogueira, “The Early History of Yellow Fever”, Yellow Fever, a symposium in commemoration of Carlos Juan Finlay, 1955, p. 2; 2 John Boyd Thacher, Christopher Columbus - His Life, His Work, His Remains, Vol. 2, 1903, p. 338; 4 Henry Rose Carter, Yellow Fever - An Epidemiological and Historical Study of Its Place of Origin, 1931, p. 157; 4 Nogueira, p. 2; 5 Carter, p. 49; 6 See Carter, pp. 80 - 186; 7 S.L Kotar and J. E. Gessler, Yellow Fever: A Worldwide History, 2017, p. 5; 8 Julie Bryant, Edward Holmes and Alan Barrrett, "Out of Africa: A Molecular Perspective on the Introduction of Yellow Fever Virus into the Americas", PLOS Pathogens website, gathered 2/17/19

Introduction of Yellow Fever to the New World 1647/8

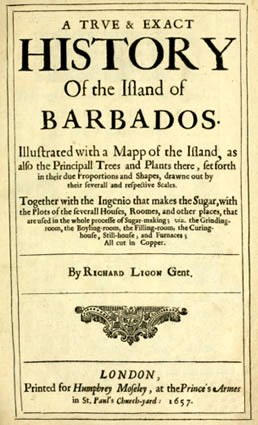

One of the more enticing suggested instances cited of yellow fever comes from the book

Richard Ligon's History of Barbados (1657)

of Richard Ligon, who arrived on Barbados in late 1647. Before coming down with it himself, he witnessed its effects, referring to it in his book as a plague "or as killing a disease", noting that "for one woman that dyed, there were ten men and the men were the greater deboystes [drinkers of alcohol]."1 He also suggested it may have been disseminated by arriving ships since "in long voyages, diseases grow at Sea"2, although he didn't rule out the idea that it might have been endemic on the island as well.

Speaking of his own bout with illness, Ligon mentions a variety of symptoms beginning with a fever, followed by 'customary' "bindings, costiveness [constipation], and consequently gripings and tortions [pain] in the bowels" which he says lasted two weeks. During this time, he notes that he couldn't sleep which "wore me out to such a weaknesse, as I was then not in a condition to take any remedy at all."3 Once the initial symptoms passed, he was slow to recover. Eventually, "my Memory and Intellect suffering the same decayes with my body, for I could hardly give an account of the time I was sick"4. This was followed by an inability to urinate, also lasting two weeks. Many of these symptoms are common to people with yellow fever.

Henry Carter, who favors 1648 as the first outbreak of yellow fever in the New World, even admits that this may have been yellow fever. He adds that the description is not clear enough to definitively state this5, explaining

There is nothing to show that this was yellow fever, unless the locality, enabling us to exclude malaria, the most usual epidemic in the tropics, be itself suspicious, and the statements ...that the case mortality was decidedly greater among men than among women. This island was much used by English vessels, apparently of all classes, as a port of call and for refitting, etc.6

Carter says that a widespread epidemic which began in 1648 was "the first one that we can certainly recognize from its description as being yellow fever."7

Photo: Carlos Reusser Monsalvez

Page of Book of Chilam Balam Ixil, In the Museo Nacional de

Antropologia, Mexico City

He explains that the Mayan Book Chilam Balam of Chumayel states that in 1648 "Occurred blood-vomit began death to our people the year 1648."8 'Blood-vomit' ('xekik') is generally recognized as the Mayan description for yellow fever, in part because vomiting of blood is one of the symptoms of the illness.

Father Diego Lopez de Cogolludo describes the same sickness in his history of the Yucatan which he says began in April or May at Merida and made its way to Campeche by June where

in a few days became so severe that the place was completely ravaged. ...With such violence and rapidity were the people attacked, big and small, rich and poor, that in less than eight days the whole population of the city were sick at the same time, and many citizens of the highest rank and authority died. . . . While the city was thus afflicted by this calamity, never before seen since this country was conquered by the Spanish nation... It is impossible to say what the disease it was, for the physicians did not recognize it.9

Father Lopez goes on to provide a very full description of the illness which included 'a most severe and intense headache', pain in the body, vomiting of blood, delirium, dysentery and, within five to seven days of it being noted, death in some cases. Young men were particularly vulnerable and although children became ill, they rarely died. Not surprisingly, the disease was transmitted west to Vera Cruz in the same year.10

This was the beginning of an epidemic. That same year, father Jean-Baptiste du Tertre said in his history of the French Antilles islands that "the plague until then unknown in the Isles, since they were inhabited by

Panorama of La Habana (Cuba), From Atlas Beudeker, (17th century)

the French, was brought there by a few ships; it began with Saint Christophe [modern St.. Kitts], and in ten months that it lasted there, it carried away nearly a third of the inhabitants."11 Like Lopez, he notes that the symptoms included a violent headache, pain 'of all the members' and continuous vomiting "so strong that in three days it put a man in the tomb."12 During the same year, the disease "was also brought to Guadeloupe by a ship from La Rochelle, called the Boeuf"13.

The disease was apparently transmitted to Cuba as well. In Cuban historian Jacobo de la Pezuela's book, the introduction says, "In the spring of 1649 Cuba was shocked by an unknown and horrific epidemic imported from the American continent. 'A third' part of its population, says the Island's unpublished History, was devoured from May to October by 'a kind of putrid fever that would snatch those attacked in three days.'"14 From this (rather incomplete) description, yellow-fever researcher and epidemiologist Carlos Finlay says the illness spread infected the island from 1649-1655, "and there is no plausible reason to doubt that it was the same yellow fever that later came to settle here."15

As a result of the rampant sickness in the area,

Artist: Gasper Van Eyck - Port Scene (17th Century)

Boston established quarantine procedures in March of 1648 "for all vessels arriving from the West Indies because of 'ye plague or like in[fectious] disease.' Apprehension was felt well into the following year, and it was not until May, 1649, that the order was repealed, '…seeing it hath pleased God to stay the Sickness there.'"16

Carter makes an interesting observation about the introduction of yellow fever to the New World. He explains that

a new species of maritime communication, the kind most apt to carry both aegypti and yellow fever, had sprung up and had undergone great development not long before and during this year. The buccaneers, French and English, mainly, but there were some Hollanders, had begun not only to prey upon Spanish vessels in these waters but to raid the towns close enough to the coast to be exposed to their attacks. And this coast seems to have been particularly troubled by these pirates for some time before. ...Both [Historians Diego Lopez de] Cogolludo, writing at the time, and [Juan Francisco] Molina Solis mention these pirates as being unusually prevalent and daring during the year 1648.17

He goes on to note that St. Kitts was a "a resort for both English and French filibusters."18 This suggests that the reason yellow fever didn't appear with the Spanish in the early sixteenth century as Nogueira and Finlay believe was because it was actually brought there by the buccaneers in the seventeenth.

1,2 Richard Lignon, Of the Island of Barbadoes, 1673, p. 21; 3 Lignon, 118; 4 Lignon, p. 119; 5 Henry Rose Carter, Yellow Fever - An Epidemiological and Historical Study of Its Place of Origin, 1931, p. 56; 6 Carter, p. 146; 7 Carter, p. 125; 9 Carlos J Finlay, "Yellow Fever, Before and After the Discovery of America", Trabajos Selectos del Dr Carlos Finlay, 1912, pp. 214; 10 Carter, p. 194; 11 Jean-Baptiste du Tertre, Histoire generale des Antilles habitées par les François, Tome I, Translation by the Author, 1647, p. 422; 12,13 du Tertre, p. 423; 14 Jacobo de la Pezuela, "Introduccion", Diccionario de la Isla de Cuba, Tomo Primero, 1863, Translated by the Author, p. 182; 15 Carlos J. Finlay, "Apuntes sobre la Historia Primitiva de la Fiebre Amarilla", Trabajos Selectos del Dr Carlos Finlay, 1912, Translated by tge Author, p. 123; 16 John Duffy, Epidemics in Colonial America, 1953, p. 140; 17 Carter, p. 152; 18 Carter, p. 153