New World Quarantine Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Next>>

New World Quarantine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 1

Artist: Claude-Joseph Vernet - A Calm at a Mediterranean Port (1770)

Some rather short-lived, quarantining of ships was also employed in ports the North American colonies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to try to prevent the spread of illnesses such as yellow fever, although the policy there was far less uniform and organized than it was in the Mediterranean where Plague Quarantine had been refined into a rather complex system during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

This first part of this article focuses on why and how maritime quarantine was used in the western hemisphere up to and including the golden age of piracy. It begins with a look at some of the terms required to understand quarantine and where they came from, then looks at the diseases it was used to try to prevent. The second part of the article examines three locations pertinent to maritime quarantine including the Mediterranean, England and the West Indies during the golden age of piracy. It briefly examines the role of the medical men in this process, the laws and rules establishing quarantine, the lazarettos where maritime quarantine was served, and ways sailors and officials found to cheat on the system for each of these three areas.

Terms

There are a number of terms associated with quarantine during the golden age of piracy, some of which are unfamiliar today and all of which have interesting backgrounds. These are worth discussing here as they relate to the sort of quarantine employed in the New World; they are also examined in detail in the article on Plague Quarantine.

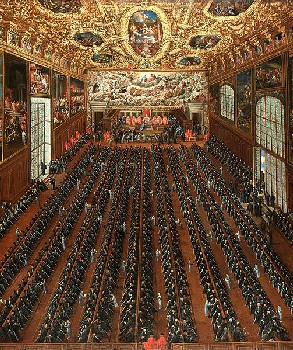

Artist: Joseph Heintz

The Grand Council of Venice (17th c.)

The first is the word quarantine which most people associate with a period of isolation imposed on people with contagious illnesses. However, it had a more specific meaning during this time which is relevant to the way it was usually performed. 'Quarantine' comes from the Italian word quarantino, which is derived quaranta ('forty'). This refers to the 40 day period established in the city-state of Venice in 1403 which was how long people were to be isolated from the local population to make sure they didn't have the plague.1 Some authors suggest that forty day quarantines "probably had a medical origin, which is derivable in part from the doctrine of critical days; for the fortieth day, according to the most ancient notions, has been always regarded as the last of ardent diseases, and the limit of separation between these and those which are chronic."2

Quarantining every vessel that came into port was difficult and pointless when a ship had already performed quarantine at another city. To facilitate shipping, letters could be issued by a city where a ship had completed quarantine during their trip which allowed them access to other ports without having to perform another full forty day quarantine. During the golden age of piracy, permission to enter a city was called pratique, an early 17th century French term which comes from the Latin word practica (or practice). John Worlidge defined this in his 1726 dictionary: "PRATIQUE or PRATTICK - a Licence to Traffick or Trade granted to the Master of a Ship, in the Ports of Italy, upon a Bill of Health, i. e. a Certificate that the Place whence he came is not annoy’d with any infectious Disease."3

Artist: Claude-Joseph Vernet

A Calm at a Mediterranean Port (1770)

The disease for which the Mediterranean maritime quarantine was created was the bubonic plague often just referred to at this time as 'the plague'. However, the bubonic plague is not a disease for which ships were generally quarantined in the New World. This isn't to say that it was unknown, just less common than other health problems which could sweep through a colony and providing no examples of quarantining in the western hemsiphere during this time..

One disease for which maritime quarantine was used in the Americas was smallpox. The clinical term for smallpox during the golden age of piracy was 'variola', which is the label which today has been given to the virus. Contemporary physician John Quincy's medical dictionary defines it: "Variolæ, the Small-Pox, a Distemper well known, and to be so variously diversify'd, that it requires a great Variety in the Method of Management."4 This term is Latin, coming from the words from 'varius' (spotted) or 'varus' (a pimple), which doctor and researcher Donald Hopkins says was first used in the 4th century to describe an epidemic in Italy and France.5 This is also (indirectly) the genesis of the name smallpox. Hopkins explains that when French King Charles VIII returned from Naples, his troops brought syphilis, which displayed a rash they thought was similar to smallpox, so they referred to it as la grosse verole, to distinguish it from variola, which now became la petite verole. Thus in English 'pox' became 'small-pox,' and syphilis became known as the 'great-pox'."6

Another disease for which a maritime quarantine was sometimes used in the New World is what is today called 'yellow fever'. The term first appears in Griffith Hughes' 1750 book on Barbados. This is the most difficult quarantined disease to identify in golden age of piracy manuscripts because it was different names by people in different places. In fact, nearly all fevers were lumped together during the this period, being differentiated primarily by their most distinct symptoms. Hughes himself explains that a Dr. Gamble, who dealt with the disease on Barbados in 1691, said "it was then called the New Distemper, and afterwards Kendal's Fever, the Pestilential Fever, and the Bilious Fever."7

In his book on malignant fevers found in Barbados and surrounding island, physician Henry Warren explains, \

Signs of Yellow Fever, From Observations

sur

la fievre jaune, Wellcome (1819)

that French speakers "call it sometimes, La Maladie de Siam ['the Siamese illness'], from a Country of that Name in the East-Indies, where it is a constant Inhabitant; sometimes they call it, La Fievre Matelotte ['the sailor's fever'], because Sea-faring People and New-comers are chiefly obnoxious to it; and probably it is the very same Fever, which the Spaniards call Vomito Preto, or the Black Vomiting, from one of its most dire Symptoms."8 Dr. Pedro Nogueira suggests that the Spanish term came from "the paper by the Spanish physician Juan Jose Castelbondo, a resident in Cartagena of Indias, which was published in 1729."9 Nogueira adds a number of other Spanish terms which he suggests may refer to yellow fever including "MODORRA ['sleepiness or drowsiness', a symptom of the fever], MODORRA PESTILENCIAL ['infectious sleepiness'] and FIEBRE MALIGNA PUTRIDA ['evil putrid fever']; in Mexico under the names of PESTE and PESTILENCIAS ['pestilence'], in Yucatan under the name of XEKIK ['blood vomit'], and among the Caribbeans under the name of POULICANTINA."10 However, Henry Rose Carter suggests that many of these Spanish names are too general to rely on them as being definitively yellow fever without more supporting evidence.11 For remainder of this article, we will defer to modern convention and call the illness 'yellow fever' even though that term wasn't used during the golden age of piracy.

1 Neville M Goodman, International Health Organizations and Their Work, Ch 2, 1971, p. 29; 2 Justus Friedrich Carl Hecker, The Black Death in the Fourteenth Century, 1833, p. 168; 3 John Worlidge & Nathan Bailey, Dictionarium Rusticum, Urbanicum & Botanicum, Vol. 2, 1726, not paginated; 4 Donald Hopkins, The Greatest Killer, 2002, p. 25; 5 Hopkins, p. 29; 6,7 Griffith Hughes, A Natural History of Barbados, 1750, p. 37; 8 Henry Warren, A Treatise Concerning the Malignant Fever in Barbados, 1741, p. 3-4; 9 Dr. Pedro Nogueira, “The Early History of Yellow Fever”, Yellow Fever, a symposium in commemoration of Carlos Juan Finlay, 1955, p. 3; 10 Nogueira, p. 2; 11 Henry Rose Carter, Yellow Fever - An Epidemiological and History Study of Its Place of Origin, 1931, p. 49

Purpose of Maritime Quarantine

The purpose of maritime quarantine was to prevent disease from spreading. In the 14th century, governments began to understand that plagues were somehow being spread by sailors so they took steps to establish quarantine stations outside of cities where incoming vessels could be isolated and their men and cargos could be either proved healthy or quarantined before they and their goods were allowed into the city.

Artist: After Allan Ramsey

Physician Richard Mead (18th c)

English physician Richard Mead wrote a widely circulated and respected treatise on the plague which highlights the methods used. He said, "CONTAGION is propagated by three Causes, the Air; Diseased Persons; and Goods transported from infected Places."1 He recommended two broad methods for prevention of the spread of contagions: "The preventing its being brought into our Island; And, if such a Calamity should happen, The putting a stop to its spreading among us."2 To stop a disease from being brought to England, he recommended a system of quarantine stations and buildings, cleansing of ships and their cargos and even destruction of clothing and cargos suspected of being tainted. To prevent the contagion's spread once the plague reached English shores, Mead recommended the system of isolation used during the Great Plague of London in 1665: "any House [which] was infected, to keep it shut up, with a large red Cross, and Lord have Mercy upon us [posted] on the Door; and Watchmen attending Day and Night to prevent any one's going in or out"3. Although England never built lazarettos, they did employ a quarantine system which involved keeping ships at anchor in isolated areas for specific periods of time. Since resources were limited in the New World colonies, this system employed there as well.

Its' effectiveness was hit-and-miss, although it was believed to be the best defense. Writing in 1791, Scottish surgeon Patrick Russel explained, "Italy has been less frequently visited [by plagues] since the establishment of quarantines and lazarettos in the maritime towns, though from the impossibility of always preventing breach of rules, they have not always proved infallible defences"4. However, as modern author Neville M. Goodman points out, "in the absence of knowledge of the modes of transmission of the pestilential diseases- or even of any clear distinction between them - as well as of rapid and reliable information of their occurrence, successes of the eighteenth century quarantines must have been largely fortuitous."5

1 Richard Mead, A short discourse concerning pestilential contagion, 1720, p. 1; 2 Mead, p. 21; 3 Mead, p. 32; 4 Patrick Russell, A Treatise on the Plague, 1791, p. 327; 5 Neville M Goodman, International Health Organizations and Their Work, Ch 2, 1971, p. 34