Memento Mori: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Memento Mori in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Memento Mori Art

There is a wide variety of macabre art from the 13th through 16th centuries and memento mori art from the 16th through 18th centuries. The origins of the macabre art style began with word of mouth stories about the dead visiting or warning the living, usually in the guise of a transi, or decaying, flesh covered corpse. These stories, in turn led to art which illustrated the story which in turn gave rise to similar art. In the 15th century, the concept of the Danse Macabre appeared, showing dancing corpses leading the living to their graves, an idea which persisted even into the 19th century. Death Triumphant art was another, more violent representation of macabre art, with death taking an active role in harvesting the living. The macabre art eventually gave way to a softer, more symbol-based art-form called Vanitas. Let's look at each of these fascinating, grisly art forms.

Memento Mori Art: The Three Living and the Three Dead

One

The Three Living and Three Dead, From Master of the Housebook,

Wellcome Library, London (~1488 - 1505)

of the earliest forms of macabre art was the story of the three living rich men or kings who encounter their three dead ancestors. The oldest versions of this story appeared in the 13th century in poems written by Baudoin de Condé, Nicolas de Margival and two unknown writers.1 The basic story is that three living men (in some stories a duke, count and prince) encounter three corpses. The corpses speak to the living, warning them to abandon their worldly pursuits. "Such as I was you are, and such as I am you will be. Wealth, honor and power are of no value at the hour of your death."2 In some versions, the three living return home and raise a church where they have the story written upon the walls.3

In some later versions of the story, the three men are hunting when they encounter their grisly counterparts. Paul Binski believes "the hunting motif is important, because it is the living hunters who are now brought to bay by death, the hunter of all men, a theme apparent in many renditions of death as an equestrian cadaver after its mortal prey."4

The story had widespread appeal. Binski notes that the legend "was fairly widespread in the thirteenth century, known in the Mediterranean and especially in Italy, where it appears to have been a significant theme of the macabre". Still, he notes that of "the sixty-odd versions of the tale, the best known were produced in France and England."5

This story of the Three Living and the Three Dead was popular from the 13th through 16th centuries, coincident with the popularity of macabre art. It began appearing as decoration in graveyards in the 15th century as a cautionary tale, sometimes appearing on sarcophagus fronts.6

1,2 Patrick Pollefeys, "The legend of the three living and the three dead", lamortdanslart.com, gathered 10/7/14; 3 "The Three Dead Kings", wikipedia.com, gathered 10/5/14; 4 Paul Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation, p. 134; 5 Binski, p. 135; 6 Herbert González Zymla, "The Meeting of the Three Living and the Three Dead, /www.ucm.es, gathered 10/8/14, p. 15-6

Memento Mori Art: Danse Macabre

Artist: Michael Wolgemut - Danse Macabre From the Book of Chronicles

Another form of macabre art that persisted well into the 17th century was that representing the Danse Macabre - Dance of Death. Danse Macabre art depicted jovial figures of death walking, dancing or playing music to summon people from all walks of life - such as popes, emperors, kings, children and laborors - to join them in the jig to the grave. In addition to visual art, Dance of Death art took the form of music, plays and poems.1

Philippe Aries explains that the dance "is an eternal round in which the dead alternate with the living. The dead lead the dance; indeed, they are the only ones dancing. Each couple consists of a naked mummy, rotting, sexless, and highly animated, and a man or woman, dressed according to his or her social condition and paralyzed by surprise. Death holds out its hand to the living person whom it will draw along with it, but who has not yet obeyed the summons."2

"Its origins are postulated from illustrated sermon texts; the earliest recorded visual scheme was a now lost mural in the Saints Innocents Cemetery in Paris dating from 1424–25."3 The Dance of Death was found in many European countries including France, Portugal, Italy, Germany, Romania and Estonia. This (and likely other forms of memento mori art) probably arose from some of the problems associated with the 14th century: famine, the Hundred Years War, and the Black Death. "The latter starkly demonstrated the way in which death united all, felling the population without the faintest regard for age or rank."4

Danse Macabre From German Broadsheet (17th - 18th c).

Note the Differences in the

Corpses and Symbols Surrounding the Danse Images from Earlier Period Danse Art

Philippe Aries explains that the purpose of the Danse Macabre "was to remind the viewer both of the uncertainty of the hour of death and of the equality of all people in the face of death. People of all ages and ranks file by in an order which is that of the social hierarchy as it was beginning to be perceived at the time."5

Paul Binski finds some other underlying motifs in the Dance. He notes that the Danse artwork "was a vigorous piece of taboo-breaking, connecting ritually purified spaces [such as graveyards and churches] to the signs of fallen human nature in the world in all its worldliness [through the act of dancing, which was prohibited in sacred places]."6

Binski also points out that the living participants in the Dance "step cautiously, [while] the dead with uncannily enthusiastic high kicks: the dead by virtue of their movement are another order, another class."7 Aries suggests, "The art [of the Danse Macabre images] lies in the contrast between the rhythm of the dead and the rigidity of the living."8 This reverse from the dancing styles that would be expected has a grimly comic aspect, which may have made the moralizing point while also providing an opportunity for the viewer to laugh in the face of death.

Artist: Bernt Notke - A Small Section of Lübecker Danse Macabre (1463) |

1 Danse macabre, wikipedia.com, gathered 10/4/14; 2 Philippe Aries, The Hour of Our Death, p. 116; 3 Danse macabre, wikipedia.com, gathered 10/4/14; 4 Brett & Kate McKay, "Memento Mori: Art to Help You Meditate on Death and Become a Better Man", artofmanliness.com, gathered 9/20/14; 5 Aries, p. 116 6 Paul Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation, p. 255; 7 Binski, p. 256; 8 Aries, p. 116

Memento Mori Art: Death Triumphant

Artist: Hans Leinberger

Death Drawing Arrows, Schloss Ambras, Innsbruck, Austria (1596)

In the story of the Three Living and the Three Dead, the dead offer the three living men the opportunity to reform their lives so that they don't suffer a similar fate. In the Danse Macabre, death assumes a slightly more aggressive role, leading the stunned living to their inevitable end, although doing so in a playful manner. In artwork representing Death Triumphant, death takes an aggressive, even menacing, face; forcefully bringing its victims to their end.

In such artwork, death is "in a furious combat with the living. The exit of the fight is obvious; the Man will be overcome by Death, which is inescapable."1 Philippe Aries points out that Death Triumphant artwork steps back from the individual nature death seen in the previous forms and presents death's collective power over humanity. "Death, in the form of a mummy or skeleton, stands with symbolic weapon in his hand".2 It employs a variety of weapons including those traditionally associated with death in memento mori artwork such as scythes, arrows and darts.

Not all of death's weapons were quite so brazen, although they were just as potent. The caption to the image seen at right explains that the picture represents the 'first

Artist: Alfred Rethel

Death The Strangler, (1850)

outbreak of cholera at a masked ball in Paris 1831'. Cholera is seen as the Egyptian-robed figure seated behind death on the right side.3 The image was inspired by an account of an outbreak of cholera in 1832 at a masquerade during the carnival of Paris by poet Heinrich Heine.4

Triumph of Death art began appearing in the 14th century, possibly corresponding to the horrors of the plague. Francesco Traini's fresco The Triumph of Death was originally believed to have been painted after 1348, suggesting it was a reaction to the black death. Later art historians changed the date to the 1330s (as historians will do), which would suggest it had nothing to do with the plague.5

Later images do feature transi corpses with death striking a menacing pose. A good example of the overwhelming power of death and the variety of armaments that were employed by him appear in Pieter Brueghel the Elder's painting The Triumph of Death, a selected part of which can be seen below. Like Danse Macabre art, this image shows individuals of various social standing being attended by death. Unlike the merry transi in Danse Macabre art, death in these images is represented by skeletons, indiscriminately dispatching their victims with a variety of weapons.

Artist: Pieter Brueghel the Elder - The Triumph of Death (1562) - Skeletons UsingAttacking Humanity Indiscriminately Artist: Pieter Brueghel the Elder - The Triumph of Death (1562) - Skeletons UsingAttacking Humanity Indiscriminately

|

,1 Patrick Pollefeys, "Triomphe de la Mort", lamortdanslart.com, gathered 10/8/14; 2 Philippe Aries, The Hour of Our Death, p. 118; ,3 "Alfred Rethel, Death the Strangler", http://darkclassics.blogspot.com, gathered 10/8/14; 4 Pollefeys, gathered 10/8/14; ,5 Francesco Traini, wikipedia.com, gathered 10/8/14

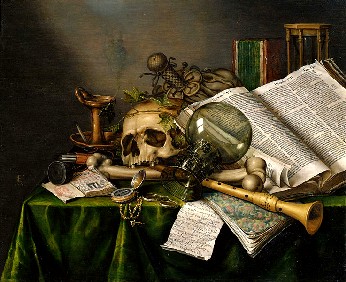

Memento Mori Art: Vanitas

Beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries, vanitas art appeared in Flanders and the Netherlands. Vanitas is

Artist: Jacob de Gheyn

Vanitas (1603)

Latin for 'vanity', which "loosely translated corresponds to the meaninglessness of earthly life and the transient nature of all earthly goods and pursuits."1 Where the macabre art gradually moved to more violent and explicit representations of death, vanitas took a step away from violence, presenting mortality to the viewer often through still life images of objects, which hinted at death with the added layer emphasizing "the fleetingness and insignificance of earthly glory and pleasures."2

The term vanitas is biblical in nature, coming from Ecclesiastes 1:2: "Vanitas vanitatum, dixit Ecclesiastes: vanitas vanitatum, et omnia vanitas" which (roughly) translates into "A shadow’s shadow, he tells us, a shadow’s shadow; a world of shadows!"3 The idea being that man's life and his existence is but a shadow. Other interpretations suggest the word "vapour", "emptiness" or "vanity" for shadow.4

Hans Van Miegroet gives Vanitas art a deeper meaning suggesting that it showed "the paradox of earthly life as contemplated by the growing middle class in the Netherlands: there was a concern that man should not be seduced by sensual experiences, but at the same time theologians had begun to celebrate the blessings of God’s creation, the extraordinary riches and beauty of the natural world. The two strands of thought were conflicting yet interrelated."5

The key to Vanitas art is in the symbolism it contains. Some of this is obvious, such as skulls and loose bones, which appear in many Vanitas pieces. Much of it, however, presents a softer focus, hinting at the fleetingness of man's life on earth. Van Miegroet explains that "an extensive emblematic vocabulary based on Italian precedents had developed in the Netherlands, giving vanitas associations to all sorts of actions and occurrences as well as to fruits, flowers and other objects from daily life."6

Artist: Pierfrancesco Cittadini - Vanitas (17th Century)

You may recall some of the other symbols listed on the previous page of this article that are associated with Vanitas art. These include short-lived objects such as the bubble, butterfly, and musical instruments (referencing the brief life of a musical note). Other symbols included candles7, smoke, "a peeled lemon, as well as accompanying seafood [which], like life, attractive to look at, but bitter to taste", and some of the more traditional memento mori symbols such as hourglasses and watches.8 Still other objects in later Vanitas art suggest the transience of human knowledge such as books, globes and astrolabes along with arms and armor that suggest the fleetingness of power.9

One of the first recognized pieces of Vanitas still-life art that didn't figure into a portrait painting was Vanitas by Jacques de Gheyn II from 1603. This painting can be seen above. The two central objects in the image are a skull and a transparent ball above it. (The transparent ball is a reference to 2nd-3rd c. Roman writer Marcus Terentius Varro's opening line in the first book of Rerum Rusticarum Libri Tres, which proclaims "for if, as they say, man is a bubble, all the more so is an old man"10. This is likely where the soap bubble symbolism came from.) The image also features a variety of other objects "including playing cards and a tric-trac game; a vase of flowers (with the expensive yet quickly decaying tulip) on the left, some coins in the middle and a smoking urn on the right [which] reinforce the explicit reference to the transience of earthly things."11

Vanitas painting enjoyed popularity beyond the Netherlands. It was particularly popular in France in the latter-half of the 17th century and found some success in Spain during that period as well. Dutch-born artist Edwaert Collier may have introduced Vanitas art into England while there in 1688-1706.12

Artist: Philippe de Champaigne Vanitas Still Life with Skull (1671) |

Artist: Edwaert Collier Vanitas Still Life with Books & Manuscripts (1673) |

1 Vanitas, wikipedia.com, gathereed 10/8/14; 2 Brett & Kate McKay, "Memento Mori: Art to Help You Meditate on Death and Become a Better Man", artofmanliness.com, gathered 9/20/14; 3 Ecclesiastes 1:2, New Advent Bible, gathered 10/9/14; 4,5,6 Hans J. Van Miegroet, "Vanitas", oxfordartonline.com, gathered 10/8/14; 7 "Glossary: 'vanitas painting'", art-history-site.blogspot.com, gathered 10/8/14; 8 Diana Scarisbrick, Rings: Jewelry of Power, Love and Loyalty, p. 161; 9 Van Miegroet, gathered 10/8/14; 10 "List of Latin Phrases (H)", wikipedia.com, gathered 10/9/14; 11,12 Van Miegroet, gathered 10/8/14;