Head Surgery Tools Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Head Surgery Tools From the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Raising the Skull

While trepanning the skull is probably the most recognizable operation to most people with any knowledge of medicine from the golden age of piracy, most surgeons preferred to find less invasive ways to cure head wounds if possible. When the skull had been wounded and the surgeon discovered it had been smashed in, a variety of instruments were employed to try and raise the depressed skull up again. Many of these instruments were used with the idea of avoiding trepanning, although some were also used after trepanation. Instruments used to raise the depressed skull include cupping glasses, elevators, the trefoil and the terebra.

Raising the Skull: Cupping Glasses

(Cucurbitulum)

Cupping is the process of taking a container which is open on one side, placing it upside down and inserting a burning match into the cupping vessel to burn up the oxygen inside. The vessel is then placed on the body, making sure a seal is created around the mouth of the it. As the container cools, a vacuum is formed which draws against the surface of the skin. The cupping procedure is often used in combination with blades called fleams to extract blood from a site as a part of humor theory. However, large cupping glasses were sometimes used on the skull when the cranium was depressed. This was mostly suggested for children, whose skulls are still somewhat malleable.

French surgeon Ambroise Paré explains that children's skulls

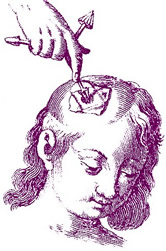

Cupping Glass, Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 4 (1706)

may be pressed down, by a great contusion, even as we see it happens in the vessels of brass, lead, or pewter... sometimes they fly back of themselves, and again acquire the former plainness and equability... But if the bones do not spring back of themselves, you must apply a cupping-glass with a great flame; withal command the Patient to force his breath up as powerfully as he can, keeping his mouth and nose Close shut; for thus there will be hope, to restore the depressed bone to its place, by the spirits forc’d upwards to the brain and skull, by the powerful action of the cupping-glass.1

German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann shows a figure "of a Cucurbitulum [cupping glass], design’d to raise a Skull up again, that by some ill Accident has been depress’d. It ought to be made of Pewter, and proportion’d to the Dimensions of the Wound. It has a great Belly, and about the Neck is sewed a piece of Leather which stand upward, to take hold of, and raise [remove] the Cucurbitulum, after it has been placed upon the depressed Skull with a considerable Flame, which by this means may be pulled up again"2.

As fantastic and interesting as the cupping glass method sounds, it is the least likely method to have been used on a ship since the sailors and even ship's boys were generally too old for the cupping to be very effective in raising the skull.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.267-8; 2 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, 1706, p. 4

Raising the Skull: Elevators

(Levatory, levatorie, levator, levetor, levitor, elevatorium)

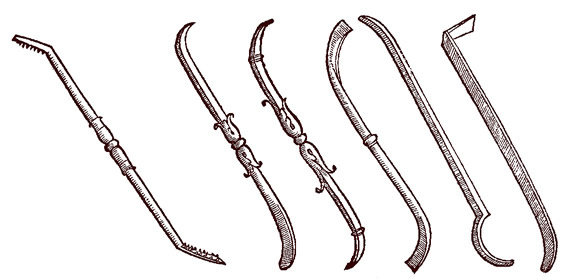

As their name suggests elevators (or levators) are used to elevate parts of the depressed skull. Several types of elevators were used during the golden age of piracy.

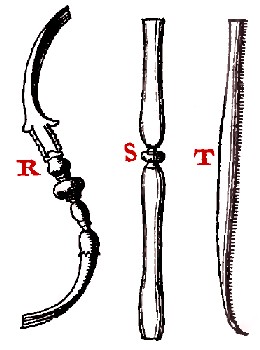

Elevators, Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical

operations (1708)

One type is a simple metal tool bent to the shape required. French surgeon Pierre Dionis describes three different types of manual elevators (which he calls levitors) for use in an ecpiesma - a fracturing of the skull in several pieces with some pressing on the Dura-mater.1

Dionis explains that when "Splinters press on the Dura-Mater, we must do our best to raise them up, or take them out, if they are not very fast fix'd. We raise them with one of the three following Levitors; the first R, is curve[d]; the second S is flat, and the third T is straight, but a little bent at the end"2.

When splinters of bone cannot be otherwise reached, Dionis says "we ought to perform the Operation of the Trepan on a firm and sound Bone near the Fracture; sliding the Levitor [elevator] into the hole of the Trepan, we raise up all the Splinters which press on the Dura-Mater; and if it be necessary to take them out, we accordingly draw out that which is the easiest loosen’d first, which facilitates the Extirpation [rooting out] of all the rest."3

Manual Elevator, The French Chirurgerie, Jacques Guillemeau

(1598)

Jacques Guillemeau also shows a manual elevator in his book, simply noting that it "at one end is toothede, and at the other end formed like unto a halfe Moone."4 Guillemeau's 'half Moone' side comes to a surprisingly sharp point at the end.

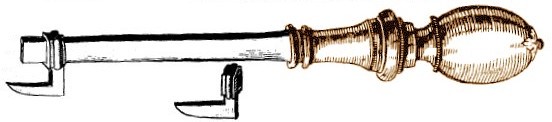

A second type of elevator has an adjustable 'tongue'. Ambroise Paré shows this type with an explanation of how it works. He says that part A, the "tongue of the Levatory [elevator]... must be somewhat dull, that so it may be the more

Adjustable Elevator 1, The Workes of that Famous

Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 269 (1649)

gently and easily put between the Dura Mater and the skull". It allows the surgeon to lift the skull "by the head or handle taken in your hand, as the necessity of the present operation shall require."4 He notes that the body of the tool, B, "must be four square [perfectly square], lest the point, or tongue put thereon should not stand fast, but the end of this Body must rest upon sound bone".5 Paré then explains its operation: "put the point or tongue under the broken or depressed bone, then lift the handle up with your hand that so the depressed bone may be elevated."6 Paré's image suggests different heights of tongues for different thicknesses of skull bone.

Adjustable Elevator, The French Chirurgerie, Jacques Guillemeau

(1598)

The key to this tool seems to be to first place the hook gently under the bone to be raised and then to slide the square shaft over the top of the bone to 'grab' it. This provides the surgeon with leverage in raising the bone. Paré's protege, Jacques Guillemeau provides similar figure of the tool, with the shape of the shaft and the varying heights of the different 'tongues' being more apparent. Note that this tool is used with the square shaft being roughly parallel to the wound.

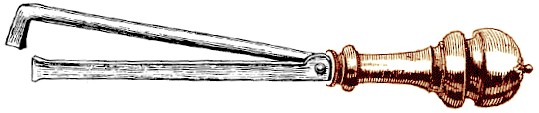

Paré figures a third type of adjustable elevator in his book, one in which an entire arm

Adjustable Elevator 2, The Workes of that Famous

Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 269 (1649)

of the tool pivots. He explains that the arm labeled C has a "crooked end [which] must be gently put under the depressed bone."7 Of the other arm, he says it "must rest on the sound bone that by the firm standing thereof, it may lift up the depressed bone.”8

Paré's drawing and explanation are somewhat inadequate for a full

Adjustable Elevator, The French Chirurgerie, Jacques Guillemeau

(1598)

understanding how this tool works. Fortunately Guillemeau provides a better drawing and explanation of this tool, which he calls the "Elevatorium bifidum". Guillemeau starts by noting that the flat end of the non-moving arm is "that which we must lay one the firme bone."9 The hooked portion of the pivoting arm is then to be hooked under "the depressed bones, to the elevation of the same."10 Thus, by sliding the hook under the bone and setting the non-moving arm at an angle to the hooked arm, the surgeon could apply force to the sunken skull. While the previous tool was used with the shaft being somewhat parallel to the wound, this one is used in an almost perpendicular fashion.

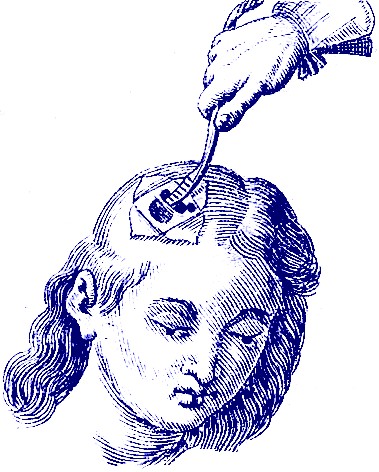

Artist: Jonas Arnold Delineavi

Elevating the Skull, Armamentarium Chirurgicum Bipartitum,

Johannes Scultetus (1666)

English military surgeon Richard Wiseman mentions using an elevator twice in conjunction with trepanning. In one case study, he reports using the elevator to remove a bullet and to pull "out the depressed Bones, with which there came away some blood and a little of the Brain."11 The use of the elevator to remove the bullet suggests that it may have been the last type of adjustable elevator which would be most likely to allow the operator to grab things, although this cannot be verified by Wiseman's account. In another case he talks about putting a 'levator' into a trepanned hole, by use of which he "raised up the deprest Bone even with the rest".12

Three of the sea surgeon writers mention using an elevator. Similar to Wiseman's use of an elevator to remove a bullet, John Moyle explains in one of his case studies how a "piece of Bone was taken out with a small Levetor and Forceps"13. Moyle's use of forceps with the elevator makes sense, particularly if he were using a manual elevator, since the elevator would be poorly suited to gripping something. He then says that he put the elevator into a trepanned hole "wherewith the Depression was raised; for the Foration [perforation] was made very near the Enclasis [hole created when the man hit his skull on something], and beneath the Suture [one of the natural sutures found in skulls, which are generally softer than other parts of the skull], on purpose to raise it."14

Manual Elevators, Chirurgiae Universalis Opus

Absolutum, Giovanni Andrea della Croce (1596)

John Woodall notes that a "Levatory [elevator] is a necessary instrument to elevate the depressed Cranium... and a fit instrument in the Surgeons chest."15 He advises his readers - who were young surgeons in training - not "to be too curious or hasty to force the depressed bone too much, where there is no evill symptoms; for a depressed bone will often-times helpe it selfe, by rising and scaling admirably"16.

John Atkins also mentions the use of an elevator, but only to report its failure to raise the skull after trepanning. He complained that when "a depressed Part has so firm a Contiguity, as to bear the Pressure of Trepanning, how absurd must it be, to think of raising it by so weak an Instrument."17 Moyle's strategic placement of a trepanned hole near a suture may explain why Atkins was unable to elevate the skull.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1710, p. 286; 2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1733, p. 276; 3 Dionis, 1733, p. 277; 4 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, 1597, not paginated; 5,6,7,8,9 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.269; 9.10 Guillemeau, not paginated; 11 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1676, p. 402; 12 Wiseman, p. 392; 13 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 13; 14 Moyle, p. 14; 15,16 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 7; 17 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 90

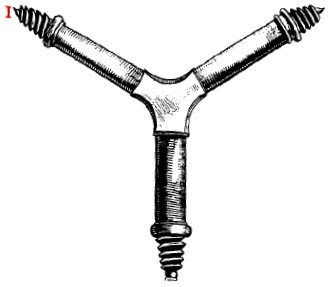

Raising the Skull: Trefoil

(Elevatorum Trepidale, Extractor, 'Drawer Out', Tripanon, Periterion, P[i]ercer, Trefine, Tirefond, Trepan)

The Trefoil is a three-armed instrument with tools at the end of each arm. There are three accounts of this tool given by our authors, each of which suggests a variety of functions could be assigned to the three tool ends, depending on the surgeon's preferences.

Trefoil, The French Chirurgerie, Jacques Guillemeau

(1598)

The first is given by Jacques Guillemeau who refers to it as an extractor or 'drawer out'. He explains that a trefoil has "three feete, the one whereof is very thinne, and smalle, notes with this figure, 1, the second is a little grosser, and thicker, notede in this sorte, 2, the thirde of a greater crassitude [crudeness] defigurede with this marcke, 3, to accommodate them according to the convientnes of the fractures, or depressions."1

Despite the fact that Guillemeau very specifically numbered each of the three arms of the trefoil in his text, the artist decided not to bother to finish labelling them after he assigned a number to the first arm. However, the basic idea is that 1 is the smallest thread, 2 is medium and 3 is large. Admittedly, which is 2 and which 3 is not entirely obvious from his drawing.

Guillemeau goes on to explain that the trefoil is used "to elevate, the depressede bones, but ...allsoe therwith [surgeons] perforatede the Cranium, and Trepanede it." From this, three possible purposes for using the trefoil are suggested. First, it can be screwed into the skull and used to elevate it, presumably by pulling up on the two other arms. Second, it can be used to make a hole in the cranium (which might be used to guide other instruments such as the pin in the middle of the trepan blade). Third, it can apparently be used to trepan the skull - that is drill all the way through it. This actually seems unlikely given the size of the instrument, but if it were used in this way, the bottom thread in his image which has a small, flattened end would probably be used. Sharp pointed ends like those found on the other arms would likely have damaged the dura mater.

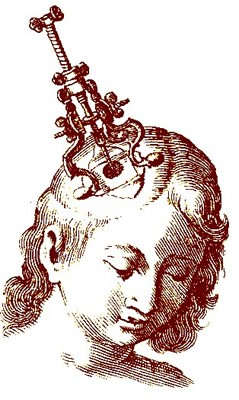

Trefoil,Johannes Scultetus, Armamentarium Chirurgicum (1674)

The second account of a trefoil comes from German physician Johannes Scultetus. He discusses a trefoil with three very different blades as seen in the image at left . Scultetus explains that this is

a trefoil, and instrument of only iron [steel], which hath three divers sorts of Trepans, the use whereof is necessary in the pricking of the skull, that doth not penetrate both the Tables [layers of bone in the skull], that with them the [im]print made upon the skul may be taken away. The triangular part of this instrument may be used also for the small Trepan, with which Giuilhelmus Fabricus Hildanus, perforated almost the first table before he applied the Triploides, with a screw.2

Trefoil Use, l'Arcernal de Chirurgie,

Johannes Scultetus (1665)

Scultetus' reference to the 'small Trepan' that only perforates the first table of the skull suggests that Guillemeau's tool (seen in the previous example) may not have been used to drill all the way through. Note the marked differences in blade types on each arm in Scultetus drawing. Also note that Scultetus does not suggest using this tool to elevate the sunken skull, which is why none of his three ends are threaded like Guillemeau's tool. It could be argued that this should be in a different classification than the previous tool.

The final description of a trefoil comes from German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann, who calls it "an Elevatorum Trepidale, which pierces into the middle of the depressed Skull, and so raises it up again. It has three Perforators, that if one should not be strong enough, the other may be used."3 Purmann's rendering of the trefoil is seen below left. His trefoil features three threaded ends, all apparently having the same size of thread. Note that he says it is only used to elevate the depressed skill.

Another trefoil by Paul Barbette which features both threaded and bladed ends can be seen below right. Clearly multiple configurations of the tool existed depending on what the surgeon wished to use it for.

Trefoil, Matthias Gottfried Purmann

(1706) Trefoil, Matthias Gottfried Purmann

(1706)

|

Johannes Scultetus (1666) |

Trefoil, Paul Barbette (1687) |

1 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, 1597, not paginated; 2 Johannes Scultetus, The Chyrurgeons Storehouse, 1674, p. 9; 3 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, 1706, p. 4

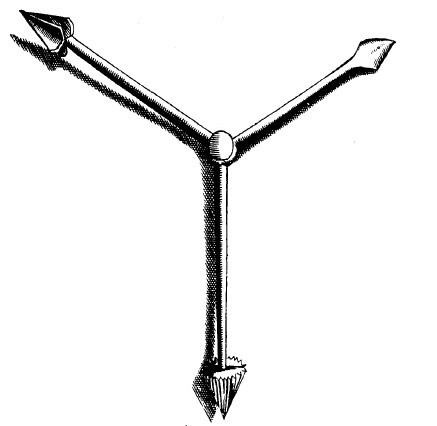

Raising the Skull: Terebra

(Levatory, Terebellum, Tirefond, Trepan, Triploides)

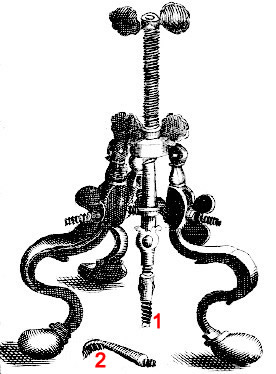

A terebra as we define it is a three legged instrument with a screw in the center.

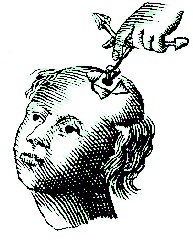

Artist: Jonas Arnold Delineavi

Terebra Use, Armamentarium Chirurgicum

Bipartitum,

Johannes Scultetus (1666)

The three legs are placed around the skull so that the screw is positioned over the place where the elevation operation is to occur. This would give it greater stability for raising the skull than any of the previous instruments. French surgeon Ambroise Paré explains that such a tool "may be applied to any part of the head which is round"1.

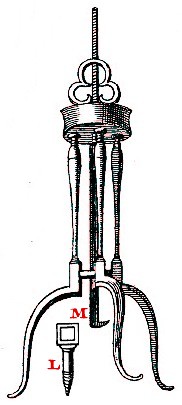

Most of the surgeons who talk about the terebra agree that it is the tool to be used when the other tools for raising the skull fail. French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis notes that when the manual elevators are "not sufficient the Chiurgion fixes another small Levitor L, to the Triploid Elevator Trepan M... which

Terebra, Dionis (1708)

we place on the Head; then by turning the Screw, which is at the upper part, we by little and little raise up what was depress'd"2.

Johannes Scultetus likewise explains that "if the depression of the skul be so great that the precedent Levitors [the manual elevators and the trefoil] are too weak to serve the turn, I set down the Levitator of the Triploides [his name for the terebra] if there be room enough, and I raise the bone pressed down, upright perpendicularly"3.

Paré suggests that when a cupping glass will not work to raise the skull "you must perforate the skull, in the very center of the depression, and with this threefold Instrument, or Levatory [the terebra], put into the hole, lift up and restore the bone to its naturall site; for this same Instrument is of strength sufficient for that purpose."4

Because most trefoils have a threaded rod in the center, various ends can be attached to raise the skull. As Paré explains, "divers [many] heads may be fitted to the end thereof according as the business shall require"5. The

Artist: Jonas Arnold Delineavi

Terebra, l'Arcernal de Chirurgie,

Johannes Scultetus (1665)

styles of attachment fall into two broad categories: a threaded screw which is screwed into the skull and a hook which is fed into an already trepanned hole and hooked under the edge of the skull.

Some of the period authors name the two types of attachments. Pierre Dionis' refers to both styles (labeled M and L in his image above) as 'small Levitors'. Other surgeons give the two styles of implements different names. German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann calls the threaded attachment the 'perforator' (1 in the image at left and L in Dionis' image) and the hook-shaped attachment the "Levatory" (2 in the image at left and M in Dionis' image).6 Recall that levatory is another word for the elevator, used to pry up the bone.

While everyone who discusses this instrument among our surgeons shows both the levator and piercer, only one explains why two different methods are used. Johannes Scultetus says that the threaded perforator (which he calls a 'piercer') is used "if there be no place for the Levitator... taking especial care that the wimble [threaded boring tool] perforate not both Tables of the skul, and so prick the dura mater."7

Opinions vary on whether the tool is useful or not. Scultetus notes that while using the terebra, "I have reduced one or two depressions with good success."8 However, sea surgeon John Atkins comments use of a terebra "is full of Difficulty. It may be asked, to what purpose then is the Skull trephined at all, either when any extraneous Body strikes there, or when depressed?"9

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.268; 2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1710, p. 276; 3 Johannes Scultetus, The Chyrurgeons Storehouse, 1674, p. 9; 4,5 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.268; 6 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, 1706, p. 4; 7,8 Scultetus,, p. 9; 9 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 85