Head Surgery Tools Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Head Surgery Tools From the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 3

Scraping

Several opportunities for scraping occur when operating on the skull. The tough membrane on the outside of the skull needs to be removed to work on the skull itself. A fractured cranium with ragged bone needs to be rasped smooth. When the trepan is applied and a hole is bored through the two layers of bone surrounding the brain, the burrs left behind by the cutting tool need to be scraped off so they don't prick the brain.

Several tools exist for scraping during head surgery. Some of them already existed for other purpose such as the spatulas and chisels. Others were created specifically for operations on the skull such as surgical rasps and various sorts of lenticulars that were used to smooth the edges of the severed skull.

Scraping: Spatulas

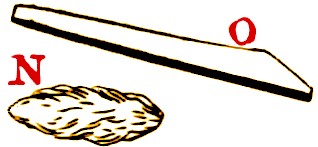

Stopple & Spatula, Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical

operations (1708)

Spatulas were used during this period, both to apply medicine and scrape the epidermis from the skull.

French surgeon Pierre Dionis suggests a spatula for applying medicine in his description of head surgery with a fracture. He explains that a wound in the skull should be "filled with two other small Stopples [wadded pieces of lint] N N, dipped in ...Digestive [a medicine that promotes the growth of healthy flesh]; and having cover’d [the wound] with the same Digestive, by [using] the Spatula O"1. Dionis provides an image of the spatula he employed for this purpose, which is nothing like the cooking implement most people think of today.

A Spoon Scraper and Spatula, From The surgions mate, by

John Woodall (1639)

Spatulas could also be made thinner for use in scraping. John Woodall shows several dual-end tools that have a spatula on one end that appear to be thin enough for scraping. Military surgeon Richard Wiseman mentions using a scalpel for gentle scraping in one of his procedures.

Then raising up the Hairy scalp smooth off with my Spatula, I both saw and felt the Bone, but could discover no fault in it. I dried up the blood with Spunges dipt in Vinegar, raised up the Lips round with my Spatula from the Bone, and with a fresh Spunge having dried up the blood, I looked again under them; but could discover nothing ill in the bared Cranium.2

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1733, p. 287; 2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1676, p. 393

Scraping: Chisels

Chisels (and the accompanying mallet used to drive them) were used both to drive the pericranium membrane from the outer layer of the skull and to plane the ragged bone of a wound to the skull.

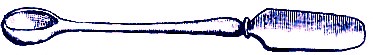

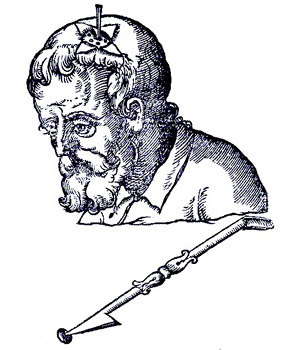

Bone Chisel, Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 266 (1649)

Ambroise Paré provides a drawing of the chisel to remove the membrane from the skull. He explains that the pericranium "must be so pluckt from the bone, or skull lying under it, that none thereof remain upon the bone; for if it should be rent or torn with the Trepan, it would cause vehement pain with inflammations. You must begin to pull it back at the corners of the lines crossing each other with right angles, with this Chissell whose figure you see here expressed."1

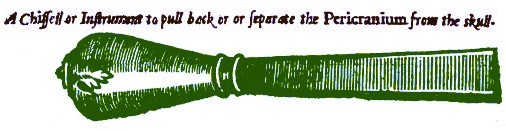

Bone Chisels & Mallet

Ambroise Paré, (1649)

In another part of his discourse on head wounds, Paré talks about using chisels and a 'leaden mallet' "because such instruments are not only very necessary to take forth the scales of bones which are broken, but also to plain and smooth those which remain whole."2 'Scales' refer to the broken edges of bone which die and fall or 'scale' off. Period practitioners typically waited for scaling of exposed bones to occur naturally before healing a wound. Paré includes a drawing of a large and small chisel and a very small mallet for this purpose. (Seen at right.)

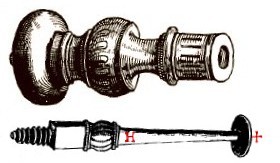

Mallet & Chisel, Pierre Dionis, A course of

chirurgical

operations (1708)

Fellow French surgeon Pierre Dionis likewise discusses the use of chisels for smoothing the bone in a head wound. He provides a bit more detail than Paré, explaining that the surgeon can use "a little Mallet Z, whose Head is of Lead, and a very sharp little Steel Chissel Δ, with which we may cut the Splinters as we would a Stone, and the Mallet being of Lead, the Blows would not so much hurt the Brian, as if it were of a harder Substance."3 His mallet seems to be of a more realistic scale than Paré's.

Artist: Jonas Arnold Delineavi

Chisel Use on Cranium, Armamentarium Chirurgicum

Bipartitum,

Johannes Scultetus (1666)

However, Dionis recommends against using chisels for this purpose, "for if a part of a piece of Bone flies out, the other end [of the bone] must be thrust in; and therefore going roughly to work to disengage that piece, we hazard the injuring of the Dura-Mater."4

One other chisel-like tool is mentioned by Jacques Guillemeau which is used for removing he pericranium membrane from the skull. This tool - which contains a scalpel on one end and the chisel-like tool on the other - can be seen on the previous page. Guillemeau explains that the chisel "end is it blunte, which is verye conveniente, to scrape the Pericranium, the same cleaving to fast unto the Craniu[m]: the which end is notede with V". The 'V' end of this tool is rather curiously designed, having been ground in a scalloped fashion to create the edge.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.266; 2 Paré, p. 270; 3,4 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1733, p. 277;

Scraping: Rasps

(Rasper, Raspatory, Rugine, Radulæ, Scalpri, Scalpra, Scraper)

Samuel Johnson defines 'rasp' as "a large rough file, commonly used to wear away wood."1 This calls to mind the traditional metal file, although the telling reference to wood suggests it is not the sort of tool that would be used by a surgeon. Johnson more helpfully defines two of the other words used by period surgeons for this tool: 'Raspatory' and 'Rugine'. For each of these words, Johnson gives the same definition: "A chirurgeon's rasp."2 He attributes the first word to English military surgeon Richard Wiseman and the second to English surgeon Samuel Sharp.

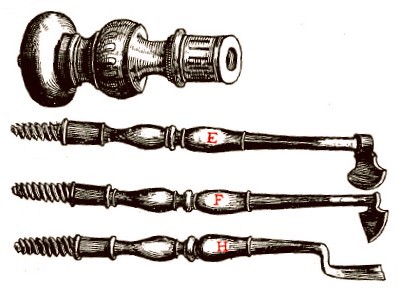

Jacques Guillemeau provides images of three types of rasps:

Handle & Scrapers, The French Chirurgerie, Jacques Guillemeau (1598)

E, F, H, Doe demonstrate unto us, the Raspes or scrapers, called in Latine, Radulæ, or Scalpra rasoria, In Greecke Xytera. There are divers, and sundrye figures hereof: that which is noted with E, is round, that which is marcked with F, is acute and poynetede. And that which is broade, & dialateth it selfe, is called in Latine, Scalper excisorius Lunatus, beinge not dislike unto a halfe Moone: and called in Greeck Cliscos, because it is like unto a semicircle3.

Guillemeau suggests in his text there there are other scrapers, "which of sett purpose I omittede, least I shoulde cloye the Chyrurgiane with to manye Instrumentes, becaus by those in place of others he might contente and suffice himselfe, because that such an infinite, numbre of instrume[n]tes doe serve more for ostentation, and pride then for anye necessarye use."4 He elsewhere suggests that scrapers are tools of the ancients no longer needed, because "we now a dayes have far more conveniente instrumentes, and we doe onlye helpe our selves therwith in searching whether the fracture doe penetrate both the Tables of the Head or not."5

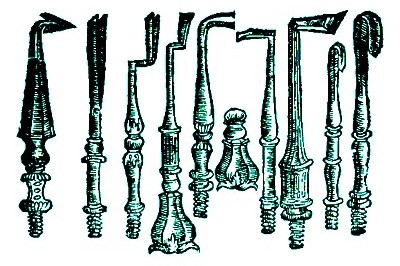

Scrapers,

Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous

Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 266 (1649)

Ambroise Paré's book discusses rasps which he explains are to be applied "to a sound bone, but as neer as you can to the fracture, so that you take away as little of the skull as is possible, lest the brain despoiled of its bony cover, take some harm thereby."6

Paré shows a variety of bone scrapers which he calls radulæ and scalpri ('Shavers' and 'Scrapers'). These tools are used on "wounded or cleft bones which may be cut out ...of which divers sorts to be here decyphered, that every one might take his choice according to his mind, as as shall be best for his purpose. But all of them may be served into one handle the figure whereof I have exhibited."7

Richard Wiseman explained that when the skull is fractured or contused, the surgeon ought "to rasp the contused Part the whole length: to which purpose you ought to be furnished with various sorts of Raspatories."8 In one of his case studies he explains, "I opened the Fissure with my Rugines,

Artist: Jonas Arnold Delineavi

Rasping, Armamentarium Chirurgicum Bipartitum,

Johannes Scultetus (1666)

scraping away its edges, that no Sanies or Matter might be detained, and drest up the Bone"9. (Rugines and raspatories both refer to rasps.)

Sea surgeons John Moyle and John Atkins both discuss the use of rasping tools. Moyle used a rasp to remove rotted and scaling bone, noting in one case where one member of the ship's gun crew hit another in the head with a 'Hand-spike',

[I] applied the Rasp to the Caries [rotting] part [of the bone]; (having stopt the Man’s Ears with Cotton before,) and having his Head held steady. I Rasped the whole Breadth of the Caries, and so deep, till I saw a sanguine Humor [blood red fluid] follow the Rasp; and in the Rasping I discover’d a Fissure, which obliged me to Rasp deeper in that place, to see if I could Rasp the Fissure out, which I did, for it vanished at the Diplois [Diploë - the spongy, porous, bony tissue between the hard outer and inner bone layers of the cranium].10

Atkins mentions this process with regard to scaling or casting off of dead bone during healing. "[I]f we would not be wanting in our Endeavours to prevent it, then we must rasp, and pierce the Cranium a Line or two [about 1/12 – 1/6 of an inch], or to the Diploe."11

Notice that rasps are not used in places where the brain is exposed. For this, lenticulars were employed.

1 Samuel Johnson, "Rasp", A Dictionary of the English Language, 3rd ed., 1768, not paginated; 2 Johnson, "Raspatory" and "Rugine", not paginated; 3,4,5 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, 1597, not paginated; 6 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.270; 7 Paré, p. 267; 8 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1676, p. 380; 9 Wiseman, p. 392; 10 John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 24-5; 11 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 88

Scraping: Lenticulars

(lenticula, Lenticuler, Scraper)

Lenticulars were used in places where the skull was open and the brain exposed and work was required next to that delicate organ. For this reason, they all have relatively broad, flat bottoms so that the dura mater - the outer membrane surrounding the brain - will not be pierced when they are being used. Several different tool shapes are called lenticulars by period surgical authors.

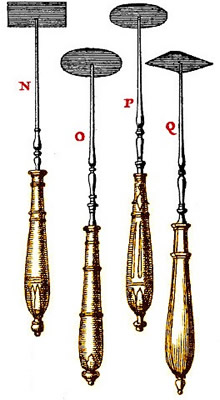

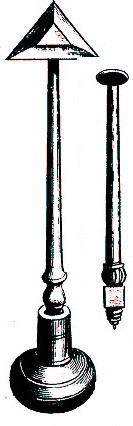

Lenticulars, Pierre Dionis, A course of

chirurgical

operations (1708)

The first mentioned use of a lenticular is to smooth the edges of an opening in the bone of the skull. French surgeon Pierre Dionis discusses four different types of lenticulars in his instructional for surgeons.

The use of these Bone-scrapers was so common, that they always had a Place amongst the Trepanning Instruments and the Cutlers to this Day put them amongst 'em, unless particularly forbidden. Of these Scrapers there are pointed, round, oval and flat ones, which were alternatively used: For instance, in a Crack or Cut, the Chirurgeon began to scrape the Wound with the flat Scraper marked N; then with the Oval one O, next with the round one P, which sunk deeper in, and finish'd with the pointed one Q1.

Dionis' lenticular bases appear to be much thinner than other examples of lenticulars found in books from this time. This might have provided exceptional scraping ability. However, after describing them, Dionis notes "at present these Bone scrapers are grown out of use, when there is a Crack, because in a Case of that sort, there is always an Effusion of Blood on the Dura Mater, which the Scraper cannot get out... wherefore we don't lose that time in scraping, which ought to be employed in the Relief of the Patient."2

Dionis is the only author to suggest that all of the different types of lenticulars were used only for scraping bone. In fact, the lenticulars found in other books that look like those he has shown are usually not used for scraping. So it is possible that he did not actually use lenticulars and may not have been intimately familiar with all their uses.

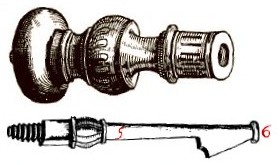

Scalper Lenticular,

The French Chirurgerie,

Jacques

Guillemeau

(1598)

One particular type of lenticular was definitely used for scraping and planing the bone. Jacques Guillemeau provides an image of this type of lenticular, explaining: "5, Scalper Lenticulatus, …It is an Instrument like unto a little chisel in forme of a penne-knife"3.

Guillemeau goes on to explain that the term 'scalper lenticular' is attached to this type. This is because although it is used for scraping the bone, the bottom has a flattened portion (numbered 6 in the image) instead of a point like the other rasps, "leaste we chaunced to hurte the membrane when we ...playne the edges of the trepanede perforatione beinge verye sharpe."4

Scraping Lenticular, Chirurgiae Universalis Opus

Absolutum, Giovanni Andrea della Croce (1596) In his book, military surgeon Richard Wiseman uses this type of lenticular after trepanning. He explains, "The Perforation made in Cranio, and the Bone taken out, you are to smooth away the Asperity which remains in the lower Table by the Lenticular instrument made for that purpose"5. He later verifies this in a case study where he explains that "the inner edges [of the trepan hole were] smoothed by the Lenticular instrument"6.

Sea surgeon John Moyle likewise notes in one of his case studies that "the inner Edg of the Foramen [opening] was smooth’d with a Lenticular"7.

Fellow Sea surgeon John Atkins advises that that once the two layers of bone in the skull have been cut by the trepan, "the Perforation is to be smoothed with a Lenticular, slipping first an unctuous Syndon, (i.e. a Bit of fine Linnen cut round, and rather larger than the Perforation,) whose Edges may slide between the Skull and the Membrane, to catch abraded Dust and Particles."8

Atkins' quote hints at another use for a lenticular; to push down the dura mater membrane inside a hole in the skull so that the syndon can be inserted without damaging it. Guillemeau refers to this type of lenticular (letter H in this image) as the

Depressor Lenticular,

The French Chirurgerie,

Jacques

Guillemeau

(1598)

depressor lenticular "which we use immediatelye after trepaninge, therwith to depresse the Membrane, to espye whether ther[e] be nothinge situatede, and collocateded between the Membrane, and the Cranium."9 He is referring here to bone splinters or dust created during the trepanning procedure. Guillemeau notes that the dura mater is pushed down by the bottom of the tool which "is flatte, as a smooth Heade, of a well pollishede Nayle."10

Two of our sea surgeon authors mention the use of this sort of lenticular after trepanning. John Woodall explains that the surgeon should have the "Lenticular at hand, to cleanse away all

Depressor Lenticulars,

Paul Barbette, (1687)

small shivers [slivers or shards] and raspings [filings] of bones, justly proceeding in the operation of excision, as also for the removing whatsoever else may seeme by consequence to offend the Dura Mater, or that way else might hinder healing."11 Woodall later reiterates this point explaining the lenticular is

a necessary Instrument, which... ought to be at hand whensoever the Trafine [trepan] is put to worke, for that there may be unexpectedly use of it, and it is as formerly named a Lenticular or smoother, being a little warmed, is to be put into the wound... and with a gentle sensible hand to be passed to and fro upon that most tender panicle, I mean the (Dura Mater) thereby to bring away any small erosions, scrapings, dust, spills of bones, or what else-soever might be imagined, could give offence to that most sensible and noble Panicle.12

Fellow sea surgeon John Moyle explains that after the hole is bored into the skull, it is to be medicated after "having first with your Lenticula taken out any extraniosities or asperities that may be fallen on the dura mater."13

In a similar way, the flat lenticulas may be used to push down the dura mater to insert medicines and bandage. In one of his case studies, Moyle uses a linen 'Sindon' medicated with oil of roses and pine resin after trepanning. "Its Edges were placed smoothly under the Coronæ Fracturæ [fracture in the skull] with a Lenticuler."14

1,2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1733, p. 276; 3,4 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, 1597, not paginated; 5 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1676, p. 381; 6 Wiseman, p. 392; 7 John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 13; 8 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 87 9,10 Guillemeau,not paginated; 11 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639, p. 316; 12 Woodall, p. 317-8; 13 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 111; 14John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 3