Fresh Water at Sea Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Next>>

Fresh Water at Sea in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 6

Problems with Fresh Water at Sea - Politics

Where ships could stop and get water was sometimes dictated by the political situation at the time. This became important when a vessel wanted to get water from an enemy held location.

Artist: Samuel Scott - English and Spanish Ships Fighting, War of Jenkins' Ear (18thc)

During wartime, an English merchant ship became a legal prize for enemy ships operating as privateers. Spain seems to have been one of the more challenging nations for English sailors. The Spaniards were in possession of most of Central and South America during this period, so if England was at war with them, English ships wanting to water there had to find uninhabited and unwatched places to seek potable water.

After sending two canoes out to find water, William Dampier reported that the buccaneers stopped at what is probably the river Rio Verde in Mexico where they met "150 Spaniards, yet they filled their Water in spight of them, but had one Man shot thro' the Thigh."1 In fairness to the Spaniards, the buccaneers had attacked several of their settlements by that time, so the encounter was a bit more than just politics.

Following an attack on Guayaquil, Ecuador and the taking of a French ship by privateer Woodes Rogers, his small fleet needed to find fresh water. Edward Cooke explains that they "resolv'd to run in for the Island Plata [in Ecuador] to water, and so come off again, for Fear of meeting with two French Ships, one of 60, the other of 46 Guns, and the Spanish Men of War, who we were advis'd would be suddenly in search of us"2.

On the other hand, necessity was sometimes considered. When Roger's ships slipped into the port of the Spanish-held island of Guam under false colors, they sent a letter to the governor of the island promising not to "molest the Settlements, provided you deal friendly by us, and [we] shall pay for all Provision and Conveniencies, either in Money, or such Necessaries as

you want."3 Of course, they followed that with a threat if the governor chose not to 'deal friendly' with them. The governor answered that he understood their 'great want'

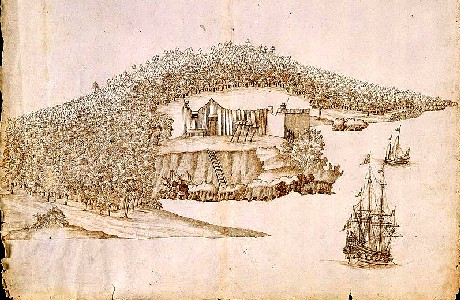

Fort Concordia, Timor, Afbeeltzel van's Comps fortresse Concordia op Timor

aen Coupan, Dutch Archives

for wood and water. "Tho' you are our Enemies, upon your paying for what you have, as you write in yours, I have ordered all under my Command to offer no Injury

to any of yours, and desire you will do the same, permitting to pass to and fro without Molestation."4 He proved to be as good as his word.

Fellow privateer George Shelvocke used a similar tactic to get much needed water from Isla Grande de Chiloe after coming round the Horn in South America in December of 1719. Shelvocke explains that when the Spanish Governor sent a man to see who they were, "I order'd, that none should appear on the deck, or, at least, be heard to speak, but such as could either speak French or Spanish. ...I hoisted French colours, and when the Spaniard came on board I told him, that we were a home ward bound French ship call'd the St. Rose"5.

Following a French pirate attack on the Dutch Fort Concordia (located in modern Kupang, Timor Island), William Dampier met with some resistance in trying to obtain water for his ships. Dampier had searched fruitlessly for water in northwestern Australia and was pretty desperate to refresh his supply. He sent his French-speaking clerk to speak to the governor there. "But the Governour replied, that he had Orders not to supply any Ships but their own East-India Company: neither must they allow any Europeans to come the way that we came and wondred how we durst come near their Fort."5 The clerk replied that they weren't there to land; if the governor would give them water, they would leave their ship where it was (about 7 miles off shore) and sail away after water had been procured. "The Governour said that we should have what Water we wanted, provided we came no nearer with the Ship: And ordered, that assoon as we pleased, we could send our Boat full of empty Casks, and come to an Anchor with it off the Fort, till he sent Slaves to bring the Casks ashore, and fill them; for that none of our Men must come ashore."6

When necessity couldn't trump politics, it sometimes resulted in a fight.

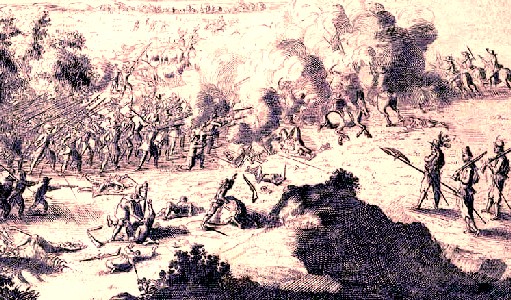

Buccaneers Attack Panama, From The Buccaneers of America, p. 163 (1678)

Raveneau de Lussan explains how the buccaneers went to Isla Iguana in Panama in July of 1681 "to see and get us some Water, not daring to go and get us any on the continent that was

guarded with four thousand men"7. Not finding it there, nor having any better options, de Lussan says, "we resolved, rather than we would die for thirst, to make a descent with

two hundred· men on the terra firma, in order to procure us some in spite of the Spaniards, whom we found about a hundred paces from the sea-side lying upon the grass"8. The fight was brief and the Spaniards quickly fled upon "seeing we were a people who would hazard all for a small matter. This being over, we presently filled some casks with water, and reembarked again."9

Captain Alexander Hamilton reported that some Indian ships who were forced to stop at Zeila (in modern Somaliland) to get water from small rivers were 'cut off' by the locals. According to Hamilton, one ship's master sent his boat ashore to get water where it was attacked. "The Boat's Crew were suprized whilst filling Water, them they killed, except two Boys whom they saved; they then came off in the Night, and those in the Ship not examining [questioning] them in Time, they boarded the Ship close to the Shore, they unladed her, and then sunk her."10 Hamilton suggests that what happened wouldn't have even been known had the boys not been sold as slaves to a ship from Surat, India and told their story.

Locals could be defensive about the use of their land. In the appendix to his book, Woodes Rogers recommended Isla Pina, Panama as a nice place to get water and even careen a ship. However, he cautioned his readers that "there are divers warlike Indians whom you must take great care of; especially, if you water above in the River [referring here either to the Rio Pina or the Rio Jaque], do not ground your Boat, and if you carry any Fire-Arms, hide 'em, and don't use them till you be provok’d."11

Not all threatening situations became violent. When stopping at Puerto Ilo, Peru to water in 1680, buccaneer Bartholomew Sharp "espyed above sixty Horse and Foot drawn up in Battalia ready to give us Battle"12. Sharp's men could have fought with them, but they didn't. Sharp reports "we minded them little, and jogged on, till we came up close with them,

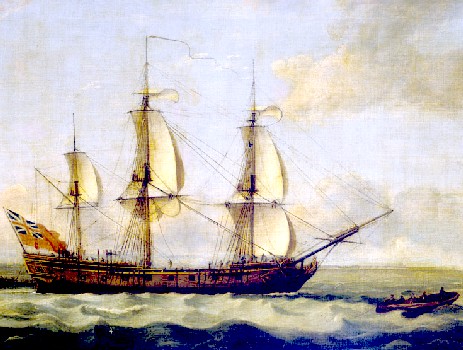

Artist: Robert Dodd - East Indiaman and Boat (between 1764 and 1785)

and then with little Resistance they yielded us the Priveledge of filling our Water and cutting our Wood"13. Seeing the lack of resistance, the buccaneers even 'made bold' to get wine, oil and other provisions.

Pirates sometimes used a merchant ships' need to stop for water to their advantage. Pirate captain John Bowen's men were refitting their brigantine Speaker while at the River Mattatana (north of what is today Farafangana) on Madagascar in early 1702 when a merchant vessel arrived seeking to refill their water. The ship was the Scotch African and East Indian Company's Speedy Return. The Speedy Return's Captain Drummond and surgeon Andrew Wilkie went ashore with some men to get provisions. While they were busy, "John Bowen, with four others of his consorts, went off in a little boat, on pretence of buying some of their merchandise brought from Europe: and finding a fair opportunity... they threw off their mask; each drew out a pistol and hanger [sword], and told them they were all dead men if they did not retire that moment to the cabin."14 Bowen and his crew took possession of the ship, burnt the Brigantine they had been refitting and provisioned the Speedy Return for their own journey.

Artist: George Roux (1885) Bowen had another such opportunity when he was sailing in company with pirate captain Thomas Howard the next year. Edward Fenwick, the supercargo of the East Indiaman Pembroke, described the encounter between his ship and the two pirates - Bowen's Speedy Return and Howard's ship Prosperous. Fenwick explains that although the ships were not not forthcoming in identifying themselves, the Pembroke's men were "obliged to discover for ourselves [who manned the two ships], being in extremity, and with this concerning the ship"15. Two pirates came aboard the Indiaman. "We acquainted them with the great necessity we were in

for provisions and water and that several of our men were down sick. They answered they had no doubt that their captain would assist us with everything and send his boats betimes in the morning."16

In the morning, the pirates sent two boats to the Pembroke, claiming they had provisions for them. The Indiaman's captain, Weoly, told them only one of boats could board, which caused the pirates to reveal themselves and threaten the crew. A gun fight followed, but the pirates "firing six shot to our one" caused the Pembroke to surrender.17 The pirates spent several days searching the ship, taking 'several things' and giving them six old pistols by way of trade. They eventually voted to give the Pembroke back to the crew, although they decided to keep Captain Weoly to act as their pilot and forced the Indiaman's carpenter to join them.

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 241; 2 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, Volume 1, 1712, p. 158; 3 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, Volume 2, 1712, p. 6-7; 4 Cooke, Voyage Vol. 2, 1712, p. 7-8; 5 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 82; 6 William Dampier, A New Voyage To Holland &c,, 1703, p. 26; 7 Dampier, A New Voyage To Holland &c,, p. 27; 8,9,10 Raveneau de Lussan/Alexandre Exquemelin, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 378; 11 Alexander Hamilton, British sea-captain Alexander Hamilton's A new account of the East Indies, 17th-18th century, 2002, p. 33; 12 Woodes Rogers, "Appendix", A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 16; 13,14 Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition," from William Hacke's A collection of original voyages, 1993, p. 41; 15 Captain Charles Johnson, The History of the Pirates, 1829, p. 50; 16 Charles Grey, Pirates of the Eastern Seas (1618-1723), 1971, pp. 233-4; 17 Grey, p. 235; 18 Grey, p. 236

Problems with Fresh Water at Sea - Lost and Broken Casks

Casks were sometimes lost or damaged on a ship while at sea which could dramatically diminished a ship's water supply. One of the most preventable was placing the water casks in a place below decks where they could not be come at without unloading the ship. This happened to privateer George Shelvocke who, after an long and challenging voyage around Cape Horn noted that the ship had "7 but[t]s of water remaining, and those lying in such a manner, that half the hold must have been unstow'd to get at them"1.

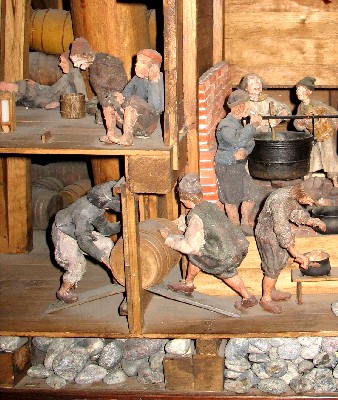

Photo: Peter Isotalo

Barrels Below Decks In a Model of the Swedish Warship Vasa

More problematic for water on ships was damage to the containers. Casks roll, particularly when the ship is experiencing violent motion. In his book of naval rules and customs, Nathaniel Boteler told his readers when preparing for battle "half butts and hogsheads of water...

[are to be] made fast in several places upon the decks"2. There were at least two reasons for doing this, both being caused by the violent movements of the ship's deck when under attack. A cask of 252 gallons would have weighed about 2520 pounds (or about a ton - a term which was was not so coincidentally derived from the word tun). If such a container got loose on the deck and started rolling, it would destroy almost anything in its path. Second, a rolling casks might either be lost overboard if it was on an open deck or broken open if it hit something.

In preparing for a battle with five French pirates near St. Jago of the Cape Verde Islands in 1686, the ship Caesar prepared to defend their ship in a way that would have made Boteler proud. They put themselves into "the best posture for defence which we did by starting down [staving by knocking in the head of] all our water casks and h[e]aving overboard all that might be of the least hindrance to us."3 Many ships from this period must have done a similarly good job in preparing for battle because accounts do not have much to say about water being lost during battles.

Weather presented another problem. William Dampier reported that in 1691 a large wave hit his ship, causing it to roll. "Such of our Water-casks as were between Decks, running from side to side, were in a short time all staved, and the Deck well washed with the

Artist: Willem Van de Velde the Younger

A Ship in Need in a Raging Storm (1707)

fresh Water. …but no harm happened to any of us, besides the loss of three or four But[t]s of Water, and a Barrel or two of good Cape Wine, which was staved in the great Cabbin."4

Pirate Nathaniel North's men encountered a storm in the East Indies which "beat in their stern, and obliged them to throw over all their guns (two excepted, which lay in the hold) and forced them into the gulf of Persia"5. Here they took several small ships in order to tear them apart so they could use the material to repair their stern. "Being very much in want of water, having staved all their casks, to save themselves in the storm, and meeting with little in the vessels taken, they hoisted out the canoe to chase a fishing vessel, that they might be informed where they should find water."6

Edward Barlow's diary noted that the ship Cadiz Merchant ran into a storm in 1681. The seas washed over the ship "damaging a great deal of goods, so that we were forced to throw overboard all our water casks which stood upon the upper deck, and we lost and staved fifty pounds worth of lime-juice, which ran out all into the sea"7.

Captain Nathaniel Uring several times broke open some of his casks of water while being chased by privateers. The first time this happened, he was captaining a mail packet boat [vessels carrying mail and packages] back to England from the West Indies in 1703. Two privateers were approaching, one of which they were able to outrun. However, "the other out-sailed us very much; which obliged us to lighten the Packet-Boat, in order to make her sail faster"8. This was first attempted by throwing all their spare wood yards and masts along with some cables [ropes] overboard and cutting off the bow anchors. This failed to work, however, so they cut off the upper deck of the ship "and threw it all over-board, and staved some Casks of Water in the Hold, and pump' d it out"9. This allowed the boat to stay ahead of the second privateer until it became dark and they got away.

Photo: Thomas Luny

A Packet Boat Under Sail With Ship Behind her (1790)

Luck was not with Uring, however. Two days later they spotted another large ship which also chased after them. We staved more Water-Casks, and pumpt out the Water, and likewise saw'd our Gun-hills [gunwales - the sides of the boat] through to the Ports on each side... in order to make the Vessel sail better"10. They were again able to escape their pursuer.

Uring recorded another such adventure in his packet boat which happened in December 1707 after they left Antigua. Two ships came after him, so Uring prepared his packet boat Prince George for a fight. However, this ships gained rapidly, at which Uring "gave Orders for lightening the Ship to make her sail better"11. They once again got rid of their spare yards, masts, cables and bow anchors along with some goods they were hauling. They "staved several Butts of Water in the Hold, and set the People to pump it out; by which Means we were in hopes to have out-sailed the Privateers"12. They failed to outrun or fight them, however, and were caught. It is notable that the water was one of the last things Uring mentions in these three accounts as being ejected from the ship.

Uring wrote about one last encounter of this nature in his book. In August of 1709, his 150 ton ship was at sea somewhere around South Carolina heading for Antigua when they sighted three privateering ships, "which immediately gave use chase."13 Uring had 16 cannon on the boat most of which he chose to throw overboard along with part of his cargo. "[W]e staved some Water and Beer in the Hold, to lighten the Ship, in order to make her sail faster; but they being light and clean Ships, out sailed us"14. They were again caught. It turned out that two of these ships were the same ones who had caught his packet boat in 1707. Fortunately, "I found [them] willing to ransome the Ship upon easy Terms... I bought her for less then half what she was worth. The Price I gave for the Ship and Cargo was Four Hundred Pounds Sterling"15.

Ships running aground present an obvious reason for emptying the tons of water a ship carried. When Barlow's ship Wentworth ran aground near Sumatra, Indonesia in 1701, he noted that "the waters were increased with the flood tide, but still we could not get afloat, so we emptied six butts of fresh water. And not long after, the water [in the ocean] being more increased, we got afloat again"16.

Photo: George Hayter - Unloading Barrels By Hand From a Ship, British Museum (1851)

Pirate Captain James' ship Alexander (where future pirate captain Thomas Howard was quartermaster) ran aground twice, requiring them to empty their water. The first grounding occurred when they got stuck on a hidden sand bar off the coast of Africa while chasing a lighter merchant ship. "This obliged the Pyrates to start their Water, and throw over the Wood [kept to replace broken spars and masts] to get the Ship off, which put ’em under a Necessity of going back to Cape Lopez [on the coast of Gabon, Africa] to take in those Necessaries."17

Once this was done, the pirates decided to head to Madagascar. During this trip, "they run the Ship on a Reef, where she stuck fast. The Captain being then sick in his Bed, the Men went ashore on the small adjacent Island, and carry’d off a great deal of Provision and Water to lighten the Ship"18. At least they don't seem to have had to knock in the heads of the cask the second time.

Sometimes the problem was a compound one. After a losing fight with a land-based force on Guam, George Taylor's log of the privateer ship Success explains how their ship got stuck on May 29, 1721. To get it off, "we clear away the hold ready to start [stave] our water to make the ship lighter"19. The next day, they used their pinnace to tow the ship off the rocks while the shore battery fired at them. Taylor's log records the damage. "Thus have we lost both our bower anchors and cables, the stream and kedge anchors, four hawsers, four of our lower deck guns, nineteen barrels of powder, two men kill'd and six wounded: having stood these fifty hours, a fair mark for the enemyto fire at: and if we had not got clear,' I do believe they would have sunk us before morning."20 So there was something to emptying the water at times.

1 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 75; 2 Nathaniel Boteler, Boteler's Dialogues, 1929, p. 292; 3 Charles Grey, Pirates of the Eastern Seas (1618-1723), 1971, p. 46; 4 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 543-4; 5 Captain Charles Johnson, The History of the Pirates, 1829, p. 196; 6 Johnson, History of the Pirates, p. 196-7; 7 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 348; 8,9 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 61; 10 Uring, p. 62; 11,12 Uring, p. 66; 13,14 Uring, p. 85; 15 Uring, p. 86; 16 Barlow, p. 521; 17 Johnson, History of the Pirates, p. 146; 18 Johnson, History of the Pirates, p. 147; 19 William Betaugh, A Voyage Round the World, 1728, p. 156; 20 Betaugh, p. 157