New World Quarantine Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 <<First

New World Quarantine During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 9

Quarantine in New York, 17th and Early 18th Centuries

New York poses some problems for accurately documenting how (and when) they employed quarantine.

Susan Wade Peabody wrote about health legislation in New York (which was called New Netherland from 1626 to 1664) and she notes in the beginning consisted "almost entirely of attempts to exclude contagious disease coming from external sources, particularly yellow fever from the West

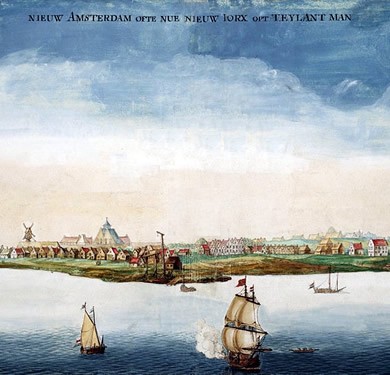

Artist: Johannes Vingboons - New Amsterdam, Soon To Be (New York (1664)

Indies, by means of quarantine applied at the port of New York"1. She says that a vessel quarantine policy was enacted by the Dutch in 1647, but she doesn't cite a source for this and the author could find no supporting information. In a note from the minutes of the New Amsterdam Council meeting of April 20, 1648, they do state that two ships which sailed from there "in consequence of great sickness and mortality [aboard] the ships Cath and Llefde must remain at Curaçao and that there was scarcely a healthy person aboard said ships"2. However, this isn't an example of quarantine; the sickness appears to have travelled from New York to Curaçao where the crew was too ill to effectively leave.

Physician and historian Aristides Moll says that New York established a quarantine against ships coming from the West Indies in 16553, but, like Peabody, he doesn't cite a source and the author failed to find supporting evidence of quarantine for this date.

More promising from an evidence point of view, a local quarantine rule was decreed in East Hampton, Long Island seven years later on March 2nd, which prohibited Indians (who were particularly susceptible to smallpox) from entering the town "upon penalty of 5s. or be whipped until they be free of the smallpoxe… and if any English or Indian servant shall go to their wigwams they shall suffer the same punishment."4 This was a land-based rule, however, and wouldn't have affected ships coming into New York's harbor.

Another comment found on an on-line article about the late 18th century Pennsylvania Lazaretto Station says, "Colonial American quarantine law began in 1663, when New York restricted entrance to the city attempting to curb an outbreak of smallpox."5 A PBS Nova article likewise states that in 1663 "the General Assembly passe[d] a law forbidding people coming from infected areas from entering the city until sanitary officials deem them no threat to residents."6 Neither of these articles provide a source and the author was not able to find substantiating information for quarantine procedures issued in New York in this year. So, if a local quarantine was enacted for ships sailing into New York Harbor before 1689, it is not clear when this occurred based on the records from that period.7

Artist: William Henry Wallace

The lower part of the canal in Broad Street (Mew York) in 1704 (19th century)

The first actual period evidence of a partial quarantine in New York comes from a meeting of the Common Council of the city held on September 15, 1689, which was applied to a specific ship. It read:

Wlliam Lynes Master of ye ship Anne & Catharina ariving here from nevis w[i]th a parcell of negroes whereof some have ye small pocks ORDERED that all w[hi]ch are sound in Body may Be Landed [after] cleaning themselves sufficiently & those w[hi]ch are seek to Be Landed a Mile or thereabouts from this City & to Permit None to Come to them but ye doctors Chirurgeons & attendors.8

In fact, once the English had assumed occupation of New York, "quarantine seems to have been enforced occasionally without special legislation by order of the governor and council with no other authority than the general powers of government conferred by the crown. Such instances occurred in 1702, 1714, 1716, 1725, 1738, and 1742"9. These are all sourced to the Minutes of the Colonial Council of New York to which the author did not have access. These were likely similar to the temporary quarantines issued in Boston quoted in the previous section. The Calendar of the Council minutes do show that the council moved their meetings to Jamaica on Long Island on October 20th of 1702 where a proclamation was issued "about quick burial of persons dying from 'malignant distemper'; about other sanitary measures and a weekly day of fast an humiliation."10

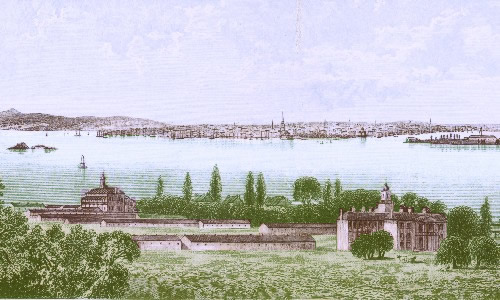

Bedlow Island (far left) in front of Jersey City, New-York, Brooklyn, and Staten Island (c. 1850)

New York did set up a temporary quarantine island shortly after the end of the golden age of piracy by taking control of Bedlow Island from owners Adolphe Philipse and Henry Lane some time after 1732. (Bedlow Island was eventually renamed Liberty Island after the statue was placed there.) According to a 20th century brochure on the Statue of Liberty, it became "the first quarantine station by the city, which feared 'that small-pox and other malignant fevers may be brought in from South Carolina, Barbadoes, Antigua, and other places,where they have great mortality.'"11 In an effort to prevent an outbreak of yellow fever and small pox from infecting the city, New York enacted legislation in May, 1755 to quarantine "all Vessels having the Small Pox Yellow fever or other Contagious Distemper on Board and all Persons Goods and Merchadizes Whatsoever coming or imported in Such Vessels and all Vessels coming from any place infected with such Distempers"12, once again commandeering Bedlow Island as their temporary quarantine ground.

1 Susan Wade Peabody, "Historical Study of Legislation Regarding Public Health in the States of New York and Massachusetts", Journal of Infectious Diseases, Supplement No 4, Feb, 1909, p. 3; 2 New York Historical Manuscripts Dutch, Vol 4, Translated by Arnold J. F. Van Laer, p. 514; 3 Aristides A Moll, Aesculapius in Latin America, 1944, p. 531; 4 Elizabeth C Tandy, "Local Quarantine and Inoculation for Smallpox in the American Colonies 1620-1755", The American Journal of Public Health, March, 1923, p. 204; 5 "Lazaretto Quarantine Station, Tinnicum Township, PA", www.ushistory.org, gathered 7/29/20; 6 Peter Tyson, "A Short History of Quarantine", pbs.org, gathered 7/29/20; 7 Documents searched for this data by the author include John Romeyn Brodhead, Documents relative to the colonial history of the state of New-York: procured in Holland, England, and France, Vols. 1-11 (1856-61), New York Historical Manuscripts Dutch, Vols 4 (1974) & 6 (1995), Translated by Arnold J. F. Van Laer, Records of the City of new Amsterdam, Vol. 1, Henry B. Dawson, Ed, 1867 & Laws and Ordinances of New Netherland 1638-1674, Translated by E. B. O'Callahan, 1868; 8 Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675-1776: 1675-1696 (Vol. 1), 1905, p. 208-9; 9 Peabody, p. 3; 10 New York (Colony), Calendar of Council minutes 1668-1783, p. 174; 11 Benjamin Levine and Isabelle F. Story, Statue of Liberty, national monument, Bedloe's Island, New York, 1952, p. 31; 12 New York, The Colonial Laws of New York, 1894, p. 1071 & Levine and Story, p. 32

Quarantine in South Carolina, 17th and Early 18th Centuries

The earliest example of the regulation of maritime quarantine for South Carolina is from 1698, when a yellow fever epidemic identified as a 'plague' broke out. The act is identified as a 'regulation of pilots and for quarantine'. This was identified as a 'resolution of the inhabitants' of Charleston South Carolina.1 It read,

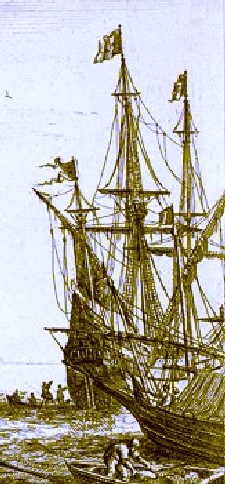

Artist: Claude Lorrain

Boats Calling on Ships at Anchor, From

Porto de Mar con Grande Torre (c. 1637-42)

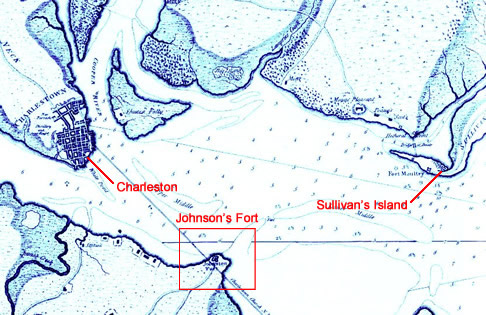

And be it further enacted, that the pylott aforesaid, shall enquire of every Master or Commander of every vessel whether any contagious disease be on his vessel, and the Master or Commander of every vessel shall give a true account thereof; and if there be any contagious sickness on board, the pylott shall acquaint the Master not to come above one mile to the Westward of Sullivan's Island on penalty of Tenn Pounds on the pylott so neglecting; and the penalty of Fifty Pounds on every Master or Commander of any vessel, and not coming to an anchor as aforesaid, after notice given him.2

However, Susan Wade Peabody notes that this this regulation does not appear in the published statutes of South Carolina.

In 1712, South Carolina passed 'An Act for the more effectual preventing the spreading of Contagious Distempers'. It explained this was designed to prevent the province from being "destroyed by malignant, contagious diseases, brought here from Africa and other parts of America". It first noted that Gilbert Guttery was in charge of "the state of health of all such personas as shall be aboard any ship or vessell arriving in this Province."3 He was

impowered and required to go on board of all ships and other tradeing vessels as soon as they come over the barr, and make strict and diligent enquiry into the state of health of that place from whence such vessel last came, as likewise of all those persons who are now on board, and into the causes of the death of such as have died on board the said ship (if any) during the voyage, and shall make such searches betwixt decks or in other places of the vessel as is necessary for finding out the truth, and shall likewise order all the men to be brought upon deck the better to be viewed and observed for the same purpose.4

The act further explained that when

any person on board the said ship is sick [or had died] of the plague, small pox, spotted fever, Siam distemper, Guinea fever, or any other malignant contagious disease... all sick persons then on board, or who may after that become sick on shore, to the pest house on Sullivant's Island, and shall order the master or commander aforesaid to lie with his ship at anchor, without sending his boat ashore, except to Sullivant's Island nor suffer any to come on board his said vessell from any place of this Province, during the space of twenty days after those orders are given5

Various penalties were to be assessed for those who didn't follow the rules of the act and the

Artist: Ed Jackson - Colonial Charles Town, South Carolina

commissioner. Ship's captains, sailors and other individuals on the ship who did not follow the commissioner's orders were fined a hundred pounds for each offense committed. Pilots who suspected 'any distemper' on a ship were to wash themselves and their clothes before coming back to shore and to pay twenty pounds. People from Charlestown who boarded ships before the commissioner examined the vessel were also to pay a hundred pounds. If they could not, "they shall be forthwith publickly whipt through the streets of Charlestown"6. Ship's masters who sent a boat ashore before being inspected were fined fifty pounds. People serving quarantine at the 'pest house' on Sullivant's Island were to pay their own way, while those who could not pay were to be covered by the ship's master.7

This act was only to be in place for two years, but it was reinstated in 1714 and 1719.8 A new act was passed in 1721 entitled 'An Act for the more preventing, as much as may be, the spreading of Contagious Distempers'. It specified the same list of illnesses as the previous act, but changed the location of the quarantine and person in charge of overseeing it. Local pilots were to have the ship "come to an anchor or lye by at a convenient place within the command of the guns of Johnson's fort... and shall direct the said master or commander of the said vessel to make immediate application to the commander of the said fort, as hereinafter is directed"9. There, the ship's captain was swear to the health of the ship's crew, passengers and any incoming slaves under oath. It then gave a role to the ship's surgeon in the process.

Quarantine Locations in Charleston Harbor, (Map c. 1776)

...the doctor, if any do belong to the said vessel, with another officer, or an officer and common sailor where there is no doctor, shall apply themselves to the commanding officer of the said fort, and answer to the following questions on oath, that is to say, Whether the place from whence the said vessel came last was healthy? Whether all the persons, passengers and negroes, imported in the said vessel, are in health, and free from small-pox, plague, fevers and all other malignant distempers? Whether any died in the voyage and if so, What distempers they died of, and how long since?10

This is one of the few regulations which specifically identifies the ship's surgeon as necessary to the process. Other communities may have chosen not to rely on the ship's surgeon because they were sometimes willing to cheat the quarantine system in the ship's favor, as we shall see.

The act went on to order ships designated as being unhealthy to perform quarantine on their ship under sight of the guns of the fort. It also specified punishment and fines for those who refused to swear to the ship's health, lied about it, tried to skip the process by not hiring a pilot to guide them into port, didn't stop at the fort or left the ship while it was under quarantine. The most striking penalty was for lying under oath, for which the captain was to pay 500 pounds, the surgeon or other officers 100 pounds each and

Artist: Bernard Lepice

'Courtyard of the Customs House' (1775)

regular sailors 50 pounds. In addition, the lying master was jailed for twelve months, the surgeon and officers for six and regular sailors for three "without bail or mainprize [having someone provide surety for the prisoner]"11.

No one was permitted to board a ship under quarantine and, if they did board, were required to stay and serve the quarantine with the rest of the crew. This act also mentioned how quarantined ships 'in want of provisions' (something not all that uncommon due to the difficulties of sailing long distances) were to be handled as well as what they were to do when there was "extremity of weather, or in hurricanes, when vessels cannot without apparent danger ride at anchor in their prescribed roads, under quarantine"12. In the first case, "the merchant to whom such vessel is consigned, or any other person as the said master shall request, to supply the same, but in such manner, and with such care and caution, as shall be directed by the Governour or commander-in-chief"13. In the second, the vessels was "permitted to weigh or slip anchor, and make the best of their way to the most commodious river or creek above Charlestown, for their security, until the said hurricane or extream storms be over, and shall then immediately weigh, and if possible return to and come to an anchor at the respective roads whence the said vessel weighed"14. It was the most thorough and specific quarantine act in use during this period.

1 Susan Wade Peabody, "Historical Study of Legislation Regarding Public Health in the States of New York and Massachusetts, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Supplement No. 4, Feb. 1909, p. 145; 2 Peabody, p. 123; 3,4,5 The Statutes at Large of South Carolina: Acts from 1682 to 1716, Vol. 2, Thomas Cooper & David James McCord, eds., 1837, p. 382; 6,7 The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Vol. 2, p. 383-4; 8 Peabody, p. 123; 9,10 The Statutes at Large of South Carolina: Acts from 1716 to 1752, Vol. 3, Thomas Cooper ed., 1838, p. 128; 11 The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Vol. 3, p. 129; 12 The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Vol. 3, p. 130; 13 The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Vol. 3, p. 129; 14 The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, Vol. 3, p. 130

Quarantine in Pennsylvania, 17th and Early 18th Centuries

During the fall 1699 an epidemic occurred in Pennsylvania which local merchant and statesman Isaac Norris called "the Barbadoes distemper: they void and vomit blood. ...It hath been sometimes very sickly [here], but I never before knew it so mortal as now: nine persons lay dead in one day at the same time: very few recover. All business and trade down."1 As explained previously, this has been identified as most likely being yellow fever.

Artist: Jean Leone Gerome Ferris

William Penn (1932)

In response to this William Penn, 'Absolute Proprietary and Governor-in-Chief of the provinces of Pennsylvania', passed in 1700 'An Act to prevent Sickly Vessels coming into this Government'. This act noted that "it hath been found by sad Experience, that the Coming and Arriving of unhealthy Vessels at the Ports and Towns of this Province and Territories, and the Landing of their Passengers and Goods, before they have lain some time to be purified, have proved very detrimental to the Health of the Inhabitants of this Province."2 The act ordered that

no unhealthy or sickly Vessels, coming from any unhealthy or sickly Place whatsoever, shall come nearer than one Mile to any of the towns or Ports of this Province or Territories without Bills of Health; nor shall presume to bring to Shore such Vessels, nor to land such Passengers or their Goods at any of the said Ports or Places, until such time as they shall obtain a License for their landing at Philadelphia, from the Governor and Council, or from any two Justices of the Peace of any other Port or County of this Province or Territories, under the Penalty of One Hundred Pounds for every such unhealthy Vessel so landing, as aforesaid3

As read, the act was rather vague about how vessels might go about getting the necessary Bill of Health. In an address to the Philadelphia County Medical Society, outgoing president Wilson Jewell pointed out in his review of the history of quarantine that no mechanisms for the procedure were specified "either in the act itself or in the minutes of the provincial council, [nor was] any person was appointed as port-physician or health-officer, to visit sickly vessels coming into port"4. Nor was any location where ships should quarantine off shore specified - it was only important that they remain at least a mile away from the shore. As a result, Jewell concludes that if the act was enforced at all, it was done 'but very imperfectly.'

In March of 1720, Pennsylvania Governor William Keith suggested that with "Plague and pestilential Distempers raging in several Countreys of Europe, And there being great Numbers of People daily imported into this colony from Great Britain, Ireland, Germany and other parts" it was incumbent upon the Council to consider "some further means than the Law"5. This again hints that the law was little used and something more substantial was needed to replace it. Keith went on, stating that

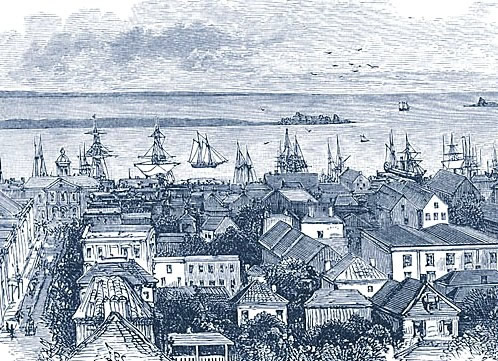

Artist: John Carwitham

View of the City of Philadelphia From the Jersey Shore (c. 1778)

Patrick Baird of Philadelphia, Chirurgeon, is authorized and required to go on Board all vessels arriving from Sea, in any port of this Province, and to examine the State of the Health of the Mariners & Passengers aboard, and upon reasonable Cause of Suspicion of any pestilential or Contagious Distemper being aboard, to warn and require the master or Commander of such Sickly Ship or Vessel not to presume to land, or suffer to be lauded any Goods or passengers from aboard the said Vessel be fore such master or Commander has obtained the Governours Licence for so doing6

The Board agreed, noting that "without the appointment of such an officer, the aforementioned Law for preventing Sickly vessels coming into this Government was lame and defective, and could not answer its first Design and Intention."7 So, although the law seems not to have been rigidly enforced before this (if it had been enforced at all), it had not been completely forgotten and was was more effectively implemented twenty-one years later.

Not much was detailed for the quarantine procedure. It is possible that the surgeon appointed to inspect incoming ships established this procedure. However, the procedure was detailed in the Pennsylvania Provincial Council's minutes a few years after the golden age of piracy in April of 1728. Two ships - the Dorothy and the Pharaoh - came into port and were rumored to have had several people die aboard during their journey. Surgeon Baird appears to have been replaced by physicians Thomas Graeme and Lloyd Zachary by this time. According tot the Council's minutes, they were "empowered ...to visit the said Ships, & make strict enquiry into the state and condition of health of those on board, and to make Report thereof".8 They verified that some of the people aboard the Dorothy had been seized by 'a malignant fever' from which fifteen people died, 'a good many' recovered and a few were still sick. No one on the Pharaoh was sick so she was allowed to land.

With regard to the Dorothy, the Board went back and looked at the regulations spelled out in 1720, which suggests they had not encountered this problem before this date. They then

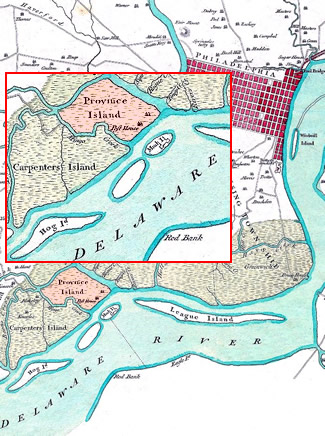

Province Island Detail (Shaded Pink) Near the City of Philadelphia

in the Delaware River (1777)

ORDERED, that the said ship Dorothy come not nearer than one Mile to any of the Towns or Ports of this Province, & that the master or Owners of the said Ship do not presume to land any Goods, passengers or Sailors, from on board her at Philadelphia, without license first obtained from this Board, under the penalty in the said Act mentioned; & that the Sheriff of Philadelphia serve the master or Owners of the said Ship with a copy of this Order; And further, that he be required to provide some convenient place at the distance aforesaid for the reception of those persons, who are still sick on board, that proper care may be taken for their recovery.9

From this we know the location of their quarantine was left to the ship's discretion. It sat in the Delaware river for nine days, after which the board met again. The two physicians reported "that all the said ship's company are now in good Health, with exception to those concerning whom they made their former Report, who have ever since been separated from [quarantined] those now on Board."10

This appears to have continued to be standard procedure until at least July of 1742 when the ship Constantine was found to be 'very sickly' by the appointed physicians but was still allowed to land their passengers. The Governor ordered the sick passengers either be sent away from the city or put back aboard the ship. Board member Thomas Lawrence said that the passengers would be put on Fisher's Island (which was renamed Province Island) where the ship "shall be well cleaned."11 This island was purchased from the estate of John Fisher and, on February 3rd, 1743, it was vested and "Buildings thereon erected and to be erected, for providing an Hospital for sick Passengers as shall be imported into this Province, and to prevent the spreading of infectious Distempers."12

However, all of this was in the future. It appears that while Pennsylvania had rules in place in 1700, the government only began to seriously consider inspecting ships with any regularity beginning in 1720, five years before the end of the golden age of piracy.

1 John Fanning Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, 1870, p. 370; 2,3 The Charters and Acts of Assembly of the Province of Pennsylvania, Vol. 1, Lewis Weiss and Charles Brockden eds, 1742, p. 9; 4 Wilson Jewell, The Historical Sketches of Quarantine, 1857, p. 10;5,6,7 State of Pennsylvania, Minutes Of The Provincial Council Of Pennsylvania, Vol. III, p. 112; 8 State of Pennsylvania, p. 293; 9,10 State of Pennsylvania, p. 294; 11 State of Pennsylvania, p. 569; 11 State of Pennsylvania, p. 638 & Hannah Benner Roach, 'Advice to German Emigrants, 1749', Pennsylvania German Roots Across the Ocean, Marion F. Egge, ed., p. 42