Medicine Containers Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

Medicine Containers Used In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Metal Containers

Like other containers used, metal containers date to antiquity. The Greeks and Romans used lead and silver containers to hold medicines. First century physician and pharmacist Pedanius Dioscorides recommended keeping medicines in thick vessels

Photo: Walters Art Museum

Byzantine Silver Pitcher (c. 550)

of silver and brass, among other materials.1 Before the use of tin-glazed ceramics, apothecaries are believed to have used metal boxes to hold medicines, although "there is a surprising lack of evidence about the storage containers used to store drugs before this period [the 1500s]."2

In the golden age of piracy, there were a variety of different metals used to fashion containers that could be used to hold drugs. Among them were silver, 'iron' (which was also used at that time to refer to steel), tin and pewter.

Silver is mentioned by William Fabry in his book on sea and military medicine chests. He suggests that balsams "be kept in Glasses, or Silver."3 Yet none of the other period references under study, including land-based physicians, suggest using silver containers for medicine. It is unlikely that a sea surgeon would prefer silver over glass unless it was necessary for the proper keeping of the contents.

The only period reference to iron as a container comes from French physician Jean de Renou, who explained that turpentine could be kept "in an iron or glass Vessel"4. Again, there are no references to such containers in the period sea surgeon's books to support the use these metals. Both iron and steel containers would quickly form rust in the usually wet environment of a ship, so they would make less suitable containers for voyages of any length than glass, as was discussed previously.

Metal Containers - Tin

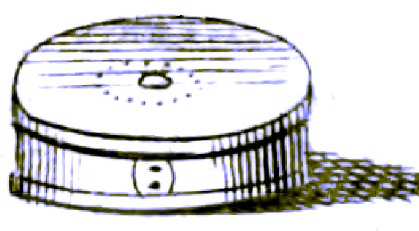

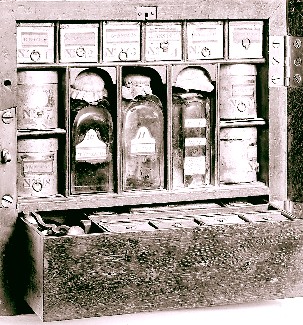

There were tinsmiths

A Variety of Square and Round Tin Medicine Containers

Surrounding Three Glass Containers, Found

in

Sir Stuart Threepland's Medicine Chest (mid 1700s)

in London in the early 17th century and tin workers were widespread in Britain by time the Worshipful Company of Tin Plate Workers was formed in 1670.5

Tin was definitely used as a medium for medicine containers at this time. A medicine chest given to Sir John Clerk of Penicuik by the Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1698 during his tour of Tuscany includes a tin box decorated with the crest of the Medici family which contains chalk antacids.6

Land-based French physician Jean de Renou suggests that liquid electuaries could be housed in tin containers, unguents could be put into "tin pots" and pottery vessels containing syrup should be kept "for carriage sake [in] Boxes of white Iron or Tin"7 ['white iron' refers to tin]. Renou goes on to say the "Syrup of Mompelian Maidens-hair, which reposed in such a [tin] vessel, may be commodiously conveyed to exotic regions"8, suggesting that the tin-glazed ceramic inside of tin boxes provided a good medium for shipping the syrup (although he does not specify whether this would be a land or sea voyage).

Tin boxes were often found fitted into the drawers of small home-based medicine chests which came into fashion shortly after the golden age of piracy in the mid 18th century.9

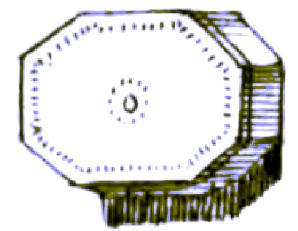

French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis' book contains two sketches of boxes that appear to be tin, although this fact is not stated in his book. (He simply calls each of them a 'box'10.) It is fairly clear that they are metal and the lines and markings suggest they are of tin. Both contain powders, one of them being caustic and thus likely to eat through wooden containers.

Despite all this evidence of its use during the golden age of piracy, tin does not even appear in any of the sea surgeon's manuals. Even John Moyle's books which contains the most detail on medicine chests and their containers, have nothing to say about tin containers. While this does not rule them out of being present in a sea surgeon's medicine chest, it does make them a less likely addition.

1 George Griffenhagen and Mary Bogard, History of Drug Containers and Their Labels, 1999, p. 3; 2 P.G. Hoffman, Royal Pharmaceutical Society, Information Sheet 14: ENGLISH DELFTWARE STORAGE JARS, 2002, p. 2; 3 Guiliem. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1674, p. 10; 5 Jean de Renou, A Medicinal Dispensatory, 1657, p. 146; 6 "Tinsmith", wikipedia.com, gathered 9/14/15; 7 Helen Dingwall and Peter Worling, “‘A box of chymical medicines’: an Italian medicine chest presented to Sir John Clerk of Penicuik in 1698”, Journal of the Royal College of Physicians Edinburg, 2012: 42, p. 365; 8 Renou, p. 146; 9 P.G. Hoffman, Royal Pharmaceutical Society, Information Sheet 16: DOMESTIC MEDICINE CHESTS, 2002, p. 2; 10 See Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1733, pages 255 & 465

Metal Containers - Pewter

One of the popular metal materials in medicine was pewter. "Pewter has been used to make containers for dry goods and bottles/flasks for liquids since medieval times."1

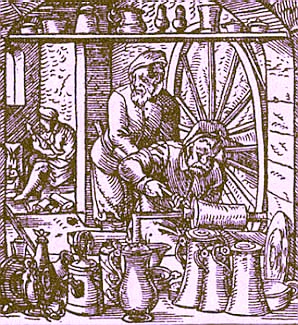

Artist: Jost Amman

Pewterers at Work, From Das Standebuch (1568)

Pewter production in England dates to about the 13th century. "From the fourteenth century pewter manufacture grew rapidly and almost every market town of any size would have a pewterer in its craft guild."2 The earliest record of a pewterers guild is found in an ordinance for the 'Craft of Pewterers' in 1348, which was connected to a religious brotherhood.3 The Worshipful Company of Pewterers, a livery company in London, has records first dating from 1451, with King Edward IV granting the company their charter in 1474. The charter allowed them to regulate workmanship standards, training procedures and the setting of prices and wages.4

Pewter is an alloy of other metals, with 85–99% of the alloy being tin. The remainder consisted of metals such as copper, antimony, bismuth, sliver and lead.5 Pewter dents and deforms easily. Re-melting old and damaged pewter items was a low-cost way to recycled damaged items, something that "could be done at any of the numerous Pewterers throughout the land, and by pedlars who went round occasionally to the houses with their moulds and tools on their back."6

As a result, pewter was widely used on land during the golden age of piracy; "by the seventeenth century there was scarcely a household in Britain that did not possess some items of pewter; plates, bowls, candlesticks, buttons - everyday items."7 Medicine also made use of this common metal. While physician Nicholas Culpeper doesn't specifically mention pewter items in his description of how to properly keep medicines, he does describe using generic pots that may have been made from pewter for keeping ointments8 and troches.9 English apothecary John Quincy also makes use of "a Lead or Pewter-Pot"10 as part of a system to store pills to keep them from drying out.

Pewter was definitely used at sea in containers before the golden age of piracy. Round and square screw-topped pewter containers of various shapes were recovered from The Mary Rose which sunk in 1545. These may have been used to store medicines.11

William Fabry's book describing medicine chests for military and sea use recommended that

Pewter Theriac Container, From the Wellcome Collection (1603)

"Unguents, and Fats are best kept in Galli-pots, or [pots] of Pewter, well tied down with Paper and Leather. And Turpentine so likewise."12 Fabry also requires that the surgeon "hath about him in a Pewter Bottle some Oyl of Roses, to anoint any wounded part, it easeth pain, &c. as also another pot with a digestive [a medicine to promote healthy flesh in a wound]."13

None of the three books written specifically for sea surgeons mention pewter being used as a storage container for medicines, however. Sea surgeon John Woodall's book, originally written in 1617, is the only sea surgeon's manual to mention pewter vessels, primarily as a place to prepare medicines for use. Even then he suggests alternatives. For example, Woodall directs his readers to "have a glyster [clyster or enema] pot of pewter, but one of brasse were better, for feare of [the pewter pot] melting."14 When directing the mixing of melted wax and an unguent with turpentine, he says it should be "put into the bottom of the wodden bowle, or brasse bason, not a pewter bason"15. The composition of the material was clearly a problem even for Woodall's simple uses. (The fact that he mentions it as a heating container does suggest some sea surgeons may have done so at that time, however.)

Overall, it seems unlikely that a golden age of piracy era sea surgeon would prefer a pewter container to store medicines over alternative materials. In addition to their potential for easy damage, pewter containers are heavier than many of the other materials we have considered which would have served the need just as well.

1 "Containers", www.pewtersociety.org, gathered 9/13/15; 2 "A History of Pewter", www.pewter.co.uk, gathered 9/13/15; 3 William Redman, Illustrated Handbook of Information on Pewter and Sheffield Plate, 1903, p. 16; 4 "The Company - Company History", The Worshipful Company of Pewterers, www. pewterers.org.uk, gathered 9/13/15; "Pewter", wikipedia.org, gathered 9/13/15; 6 Redman, p. 12; 7 "A History of Pewter", gathered 9/13/15; 8 Nicholas Culpeper, The English Physitian Enlarged, 1666, p. 282; 9 Culpeper, p. 283; 10 John Quincy, Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea, p. 421; 11 "Containers", www.pewtersociety.org, gathered 9/13/15; 12 Guiliem. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1674, p. 11; 13 Fabry. p. 24; 14 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 19; 15 Woodall, p. 50

Metal Containers - The Burras Pipe

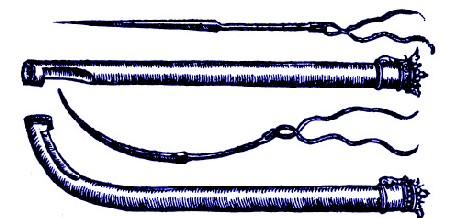

One metal container is specifically mentioned by sea surgeon John Woodall: the burras pipe. (This is discussed in greater detail in the article on cauterizing tools.) Woodall says that this pipe is used "for the most part to reteyne corroding powders in, as Vitrioll, burnt Allom præcipitate, and such other causticke medicines1.

Woodall

Suture Needles and Cannula Pipes - The Right Side of the Tubes are Hollow

With Caps on the End To Keep Items Inside the Tube (Needles & Cauteries),

From The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p256 (1649)

gives very little information about this device or its makeup. Other descriptions of a burras box suggest this device Woodall's burras pipe is based upon would have been a copper or brass box with a pipe sticking out of one side of it.2

Surgeon James Cooke gives another explanation, noting that a stitching quill (or cannula), needles and a burras pipe "may [all] be included in one [instrument]... The burras pipe is to preserve in it corroding powder, as [mercury] precipitate, turbith mineralis, burnt allum &c. to cast on proud flesh [flesh growing where it shouldn't in a healing wound], appearing in the wounds and ulcers."3

This importance of Cooke's comment is that it says a cannula can function as a burras pipe. Seen in the image above, a cannula is a metal tube, made from steel or possibly silver, which has an enclosed tube (or pipe) with a lid at the back of it. (The back is on right side of the image - the cap is the crown-like part.)

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 31; 2 Randle Holme, The acadamy of armory, Volume 2, 1688, p. 308; 3 James Cooke, Supplementum Chirurgiae, 1655, p. 419-21

Other Containers

While not nearly as grand as glass, ceramic or metal in most people minds, paper, cloth, leather, bladder and wood containers were no less important to the keeping of medicines during the golden age of piracy.

Other Containers - Paper

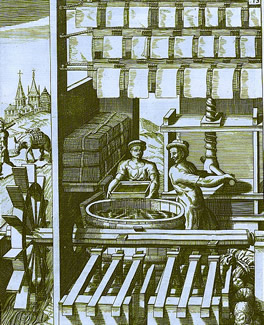

17th Century Paper Mill, From Georg Andreas

Böckler's Theatrum Machinarum

Novum (1661)

Paper has a long history dating back to 1st century China. Handmade paper wasn't produced in Europe until around 1300; it is notable that this seems to have occurred independent of the Chinese process.

The first paper maker of record in England was John Tate, who established a paper mill near Hertford and began producing paper around 1494.1 Tate died in 1507 and his mill died with him. The first commercially successful paper mill was set up by John Spilman, a German entrepreneur, who began producing white paper in Dartford, Kent in 1588. Through political savvy, he maintained a virtual monopoly on materials needed to create white paper in Britain until 1597.2 However, there were thirty seven paper mills in England from 1588 to 1650, most of which produced brown paper.3 The inferior brown paper was cheaper than white and thus would be the type most likely used to wrap medicines.

Paper was used at this time to contain a variety of medicines. English physician Nicholas Culpeper suggested that troches (lozenges) such as those of Wormwood and Galanga could be kept by a patient "in a paper in his pocket (while a man travels) and [are] more convenient behalf than to lug a Gallipot along with him."4

While explaining the make up of military and sea chests, William Fabry recommended that "prepared Tutia [tutty], Seif Album [white sand], Ostiocolla [lime carbonate],

Photo: Mission - Folded Brown Paper of Cloves

and the like... are to be wrapt up in Paper, and put into Leather-bags, and plac’d amongst the Cordials [in the medicine chest]."5

Sea surgeon John Moyle provides a little more detail on how paper would be used to contain medicines. He advised readers to store "dry things that are done up in Papers; carry a single Drugg Chest, and let them be decently stowed there."6 Moyle elsewhere explains, "'Tis usual to put your Farrina's [wheats], Seeds, Roots, Herbs, [dried] Flowers, and such like in Papers... but do you put these papers into small Canvas Bags.... Let several of these Papers be put into one bag; as, the several papers of seeds into one bag, the herbes into another, the roots into a third, and so the rest."7

While paper was a recommended medium for storing dry items, it apparently had its downside if not stored in bags as Moyle recommended. "Let the things be in bags, because papers break in rummaging, and spill about the bottom of the Chest, mixing one thing with another."8 The fact that both Moyle and Fabry advised putting paper containers into more durable bags recognizes this obvious limitation of the material.

1 "An Introduction to Printing", britaininprint.net, gathered 9/14/15; 2,3 Neathery Batsell Fuller, "A Brief History of Paper," stlcc.edu, gathered 9/14/15; 4 Nicholas Culpeper, The English Physitian Enlarged, 1666, p. 283; 5 Guiliem. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1674, p. 11; 6 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 43; 7 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, p. 17; 8 Moyle, Abstractum, p. 18

Other Containers - Cloth

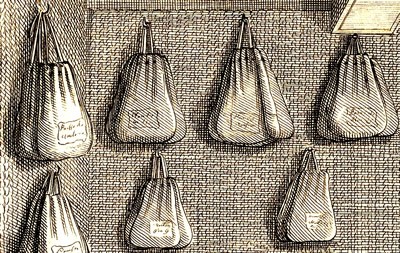

Artist: Abraham Bosse

Labeled Cloth Bags, From The Prosecutor's Study (mid 17th c.)

As seen in the previous section, sea surgeon John Moyle advised wrapping dry ingredients in paper and then putting "these papers into small Canvas Bags"1, grouped by type. William Fabry skips the use of paper containers, recommending that "Roots, Herbs, Flowers, and Seeds are... to be kept in bags of Leather or Linnen"2.

Moyle also orders his reader to "See that your Rhubarb be new and sound, and that the worm hath not go into it... let it be wrapt in Cotton, and kept in a Box dry."3 In a related vein, French physician Jean de Renou advises his reader that roots are "wrapt sometimes in bombast [padding – often cotton]; if pretious [precious], as Chinean Rhabarb, lest the noxious quality of the air, or edacity [voraciousness] of heat, spoyl their qualities, and corrupt them."4

1 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, p. 17; 2 Guiliem. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1674, p. 10; 3 Moyle, p. 13; 4 Jean de Renou, A Medicinal Dispensatory, 1657, p. 146

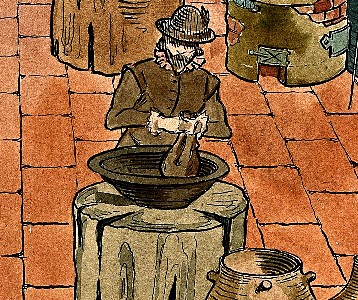

Other Containers - Leather

Artist: Vzcaslav Kaliba after 17th c. Artist K. Stapfer

Alchemist Tying Up Leather Bag From Wellcome (1934)

Leather could be used to either individually wrap medicines or to make bags that would hold an assortment of medicines. William Fabry is the only author to recommend using leather.

He explains that roots, herbs, dried flowers and seeds should first be wrapped in paper and then the papers placed in leather bags1, as mentioned previously. There may well have been something in this. Leather is a tougher material and would have been more impervious to punctures and tears.

Fabry also recommended that raw purging ingredients (simples) "must be put up in Leather-bags"2. He further directed that the "Bags again are to be put into other larger [bags]"3, presumably also of leather, although this is not stated explicitly. He further advises the reader that "Pills are to be wrapt up' in white leather, rubb'd first with oyl of sweet Almonds" and "Cordial Powders and Electuaries, being put in to leather bags, are to be so plac'd in a separate classis [places in the medicine chest], that they may not mix with the Purgers."4

1 Guiliem. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1674, p. 10; 2,3 Fabry. p. 9; 10 Fabry. p. 10

Other Containers - Bladders

Bladders refer to animal bladders removed from slaughtered animals such as pigs, sheep, cows and goats. Bladders are lightweight, very elastic when fresh and naturally air- and liquid-proof, making them a fairly unique natural storage container. They were also plentiful. Bladders were prepared by being "well washed and scoured with Red-wine"1.

Artist: Isaac van Ostade

Children Blowing Up a Bladder, From The Dismemberment of the Pig (1645)

People had a variety of uses for bladders during the golden age of piracy. The first inflated balls were made using inflated pig bladders.2 Several paintings from this time period show children blowing up and playing with such 'inflated balls'. Artists kept their paints from drying up by putting them into "a pig's bladder sealed with string"3. A simple medieval instrument similar to a bagpipe with a single pipe used sheep's bladders as an air reservoir; the instrument was even called a bladder pipe.4 Bladders were also used as sausage casing in Germany, particularly for traditional foods such as ventricina and sobrassada.5 The oldest condom discovered to date (1642) was made from an animal bladder.6 So the function and use of bladders were well understood by the general populace in the 17th and early 18th centuries.

This elastic, fluid-impervious material did not escape the attention of surgeons. In surgery, bladders were used to cover the stump of a dismembered limb to prevent fluids from leaking out shortly after the amputation was finished.

A Dismembering [Amputation] Bladder, From

Cours

d'Operations de Chirurgerie, By Pierre Dionis, p. 500 (1708)

Sea surgeon John Woodall recommended that surgeons who dealt with Mercury should "put a bladder on his hands, for the often use thereof causeth many evils."7

Their qualities made bladders useful medium for containing certain medicines as well.

Land-based English apothecary John Quincy advised keeping a couple medicinals in bladders. He noted that the fœtidæ pill "does not keep well, unless great Care be taken of it, because it will grow dry, mouldy and crumbling. The best way is in an oily Bladder close tied, and kept in a Lead or Pewter-Pot."8 Similarly, he explained that the euphorbium pill "soon dries, and will sometimes be mouldy; it ought therefore to be kept in a Bladder"9.

William Fabry had more uses for bladders. "Plaisters, Gums, Wax, the Sewet of Bears, Cows, Goats, and the like, which are of a solid consistence, are to be put in Bladders wrapt afterwards in Paper."10 The bladder would make sure that the oily plasters, gums and fats wouldn't soak through the paper.

You may also recall that when using glass bottles that weren't double-glassed, sea surgeon John Moyle noted that it was "accustomary to put them into Bladders, as well to save what is in them, (if any one should chance to break) as to preserve other Medicines from being spoiled"11.

1 Kenelme Digbie, The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Kt. Opened, 1669, reprinted 1967, p. 181; 2 "The History of the Soccer Ball", soccerballworld.com, gathered 9/15/15; 3 Perry Hurt, "Never Underestimate the Power of a Paint Tube", Smithsonian Magazine, May 2013, gathered from the internet 9/15/15; 4 "Bladder pipe", wikipedia.com, gathered 9/15/15; 5 "Pig Bladder", wikipedia.com, gathered 9/15/15; 6 "History of Condoms", wikipedia.com, gathered 9/15/15; 7 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 50; 8 John Quincy, Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea, p. 421; 9 Quincy, p. 427; 10 Guiliem. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1674, p. 11; 11 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, p. 14

Other Containers - Wood

Wood can either seem an odd choice or an immediately recognizable one for medicine containers.

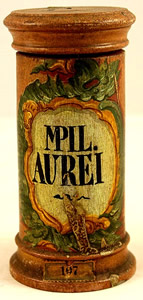

Photo: Christoph Braun

Wooden Apothecary Jar for

Pilulae Aurei (early 19th c.)

Certainly the medicine chest, instrument chest and the salvatory were all wood containers for medicines, albeit indirectly. (They often contained other containers.) However, there were some wood containers that directly contained medicines, which is what this section focuses on.

Wood has a long history of use for preserving medicines. First century Greek physician Pedanis Diascorides suggested limewood boxes be used to store botanicals and aromatic substances1.

Closer to the golden age of piracy, French physician Jean de Renou suggested boxes could be used to hold a variety of medicines including solid electuaries, gums, minerals, animal parts and even Juices.2 Renou also notes that seeds which had been recently dried should be "reposed in glass or wood vessels, and kept in a dry place. Roots after purgation and arefaction [drying] are reserved in wooden Boxes or Chests"3.

Wooden 'vessels' were popular in the mid-17th century, although their ability to hold liquids seem dubious. George Griffenhagen explains that "the more widely employed drug containers in central Europe during this period [the 18th century] were made of wood. Commencing in the 17th century, tall cylindrical containers of boxwood or linden wood were used for storing dried botanical drugs."4 William Fabry, describing medicines for sea and military use, suggests similar woods for boxes to contain unguents, explaining that they "ought to be made of Horn, or some solid wood, as Ebony, Guaiacum, or Box[wood], for unguents are better preserved in wood than in Silver, Copper, &c."5

1 George Griffenhagen and Mary Bogard, History of Drug Containers and Their Labels, 1999, p. 3; 2,3 Jean de Renou, A Medicinal Dispensatory, 1657, p. 146; 4 George Griffenhagen, "Evolution of Drug Containers", Apothecary's Cabinet, No. 8, Fall 2004, p. 6