Head Surgery Tools Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 <<First

Head Surgery Tools From the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 6

Cutting Bone: Trepans and Trephines

(Trapan, Trepane, Trafine, Chynicida, Chenicion, Prionacharacton, Modiolas, Abaptiston, Gimlet, Terebellum, Trepanum)

Photo: Peter Crossman

Wooden Brace Drill From

The Mary Rose (pre-1545)

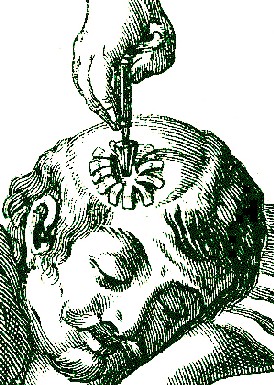

Samuel Johnson tells us that a trepan is an "instrument by which chirurgeons cut out round piece of the skull"1 and a trephine is "A small trepan; a smaller instrument of perforation managed by one hand."2 Johnson's explanations are not very clear about the differences between the two tools. Several period sources show the trepan as looking remarkably like a brace drill with a trepanning bit at the bottom. Period sources show a trephine as a T-handle style tool with a similar bit. This is why Johnson indicates a trepan is 'smaller' and can be 'managed with one hand'.

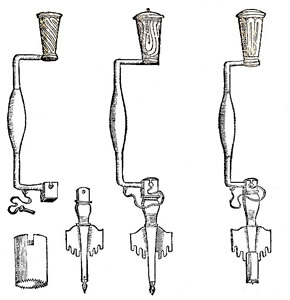

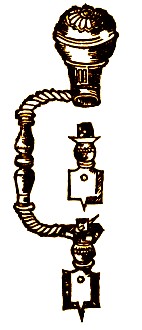

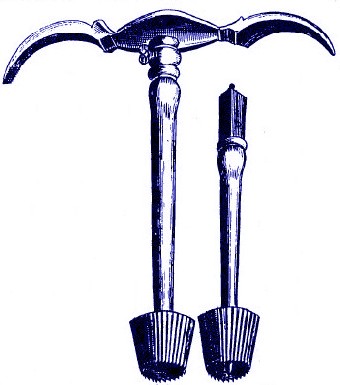

Trepans, From Chirurgiae Universalis Opus

Absolutum,

Giovanni Andrea della Croce (1573)

The trepan is the older of the two tools. A simple wooden brace drill was found aboard the the Mary Rose which sank in 1545. This is not a tool for use in surgery, but a carpenter's tool created for use in maintaining the ship.

A more modern-looking metal brace trepan with a wooden handle on top can be seen in an illustration in Giovanni Andrea della Croce's 1573 book Chirurgiae Universalis Opus Absolutum, seen at right. The brace-style trepan continued to be used well into the 19th century.

There are some interesting elements in Andrea della Croce's drawing not found in later images. Note that the key that used to loosening the screw that held the bit in place is tied to the handle. Also notice the interesting way the different sized blades were installed. By the golden age of piracy, this style of blade was not found in the literature, possibly because there was no way to secure the round blades and prevent them from falling out.

Trefine, the surgions mate, John Woodall (1639)

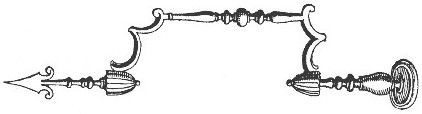

In contrast, a trephine was a much simpler affair, being designed in the shape of a T. This particular design was invented by sea surgeon John Woodall3 who felt it was an improvement over the brace-style trepan as we shall see. Woodall originally called it a trefine in reference to the three ends - tres fines, but English military surgeon Richard Wiseman referred to it as a 'trephine' in a case study found in his 1676 book Several Chirurgical Treatises4. Samuel Johnson used Wiseman's books as a source for his popular dictionary, so this may explain why the inventor's spelling of the tool name he invented was changed.

Woodall explained that the three ends of the tool each had a function. The bottom of the T held the trepanning blade. The two arms of the T were obviously for gripping and turning the trepan blade by hand, They also functioned as elevators the way that Woodall designed them, providing "the necessity of a Jagged or toothed Levatory [elevator]... the said Levatories being all necessary adjutors [assistants] in helping to make and finish the Trafine"5.

Author John Woodall

Woodall provided some thoughts on the design of the tool that apply equally to both traphine and trepan. "First be sure the instrument of it selfe be good, and of the best making, and that it be cleane from rust, and perfect without faults."6 He elsewhere advises that the tool "be truly made of good steele, I meane the head of the pinne or center... and that the pinne stand fast on, and directly in the middest of the head thereof, namely in the true center of the Instrument"7. The pin was used to guide the trepan while drilling and if it not properly centered, the blade would not run true and would cause more damage to the skull than necessary.

Being such an important instrument in the surgeon's arsenal, the trepan receives a lot attention in period surgical books. Several elements of the instrument are discussed at length by various authors including which of the two tools was preferable in surgery, what sorts of blades were used and how a trepan brush could be employed during the surgery.

1 Samuel Johnson, "Trepan", A Dictionary of the English Language, 3rd ed., 1768, not paginated; 2 Johnson, "Trephine", not paginated; 3 Sir Geoffrey Keynes, "John Woodall, surgeon, his place in medical history", Journal of the Royal College of Physicians London, 1967, 2: p. 33; 4 Richard Wiseman, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1676, p. 393; 5 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639, p. 313; 6 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 4; 7 Woodall, 1639, p. 316

Cutting Bone: Trepans and Trephines - Preference

Some surgical authors expressed a decided preference for the trepan over the trephine and vice versa.

Military surgeon Richard Wiseman spoke primarily of the brace-handled trepan in his book, "which I much prefer before a Trephine, it being an Instrument which doth its work lightly, and cutteth Bone equally, or how

Author Richard Wiseman

you please, without pressing so heavily upon the Head, and is approved by all the Chirurgeons abroad, being much to be commended before the Trephine."1

Apparently his patients agreed with him, although it is quite likely he influenced their decision. Wiseman explains that when preparing to trepan a patient, "the Patient’s Relations and Friends desired to be informed what Instruments we would use, and asked to see them. I shewed them a Trepan and Trephine, and gave them liberty to try both upon a Scull. They did so, and unanimously preferr’d the Trepan, which accordingly I set on"2.

John Woodall naturally preferred the trephine he designed. Woodall noted that "it may be said to be derivative or Epitomy of or from the Trapan; yet well observed, it performeth as much as the Trapan in every degree and more"3. He then gave a variety of reasons why he thought the trephine was better than the trepan in a rather rambling fashion, although only one applies directly to the T-handled design of the instrument - the trefine didn't require to the surgeon to lean upon it as he felt the brace-handled trepan did. (For a full discussion of this, see Trepanning Operation - Boring the Hole in the Skull in the article on Head Surgery During the Golden Age of Piracy.)

Photo: Mission's Camera

The Author Trying to Decide Between the Trefine (left) and

Trepan (right).

Woodall's other reasons for preferring the trephine actually have more to do with the way he designed the blades. Since the blades were usually removable on both the trepan and the trephine, blade design changes Woodall made for the trephine could have been easily adapted for use on a trepan. We will go into greater detail on the different types of trepanning blades in the next section.

John Moyle doesn't say anything about instrument preference, although he consistently refers to the trefine in his instructional books (calling it the 'Traphine'4). However, he also mentions the 'trepan' in the case studies featuring operations at sea in his Memoirs.5 While this article consistently refers to the trepan as a brace-handled tool and the trefine as the T-handled, 'trepan' could be used to refer to either tool. The term 'trefine' seems to have been largely restricted to the T-handled tool (particularly for sea surgeons from this period, most of whom would have read Woodall's book whice explains the difference.) So it is difficult to pinpoint which type of tool Moyle was indicating in his Memoirs.

Sea surgeon John Atkins liked using both instruments because they allowed him to take advantage of their differing qualities.

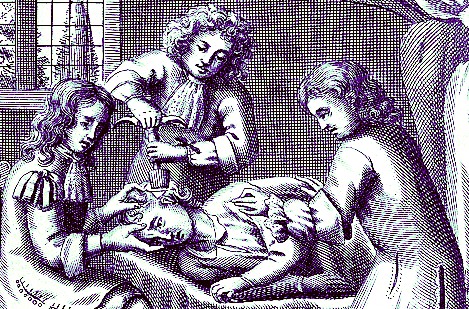

Trephining, A Complete Discourse of Wounds, By John Brown, From

The Wellcome Collection (1678)

The Trepan in the Beginning is best for Dispatch [speed], and fixing the Crown [making the first few cuts with the round blade into the skull], but the Traphine is safest, to conclude the Operation with; because the Manubrium [handle], in this latter is fixed, and moved from Right to Left, and so back again at half Turns; the Conveniency of which... is, that we have a greater Command [control] of the Instrument; and as the Perforation is found nearer through in one Part than another, we can accordingly bear more on the thickest Side, to bring it to an Equality6

There may also have been regional differences. Historian John Kirkup explains that the trephine was "popular in Britain thanks to John Woodall’s exposition in The Surgeon’s Mate" while Wiseman may have preferred the trepan "perhaps as a result of his European experiences"7.

1 Richard Wiseman, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1676, p. 393; 2 Wiseman, p. 397; 3 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639, p. 313; 4 See for example, John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, p. 51 & John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 109-10; 5 See John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 13 & 20; 6 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 86;7 John Kirkup, Introduction to Richard Wiseman's Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1676, p. xvii

Cutting Bone: Trepans and Trephines - Trepanning Blades

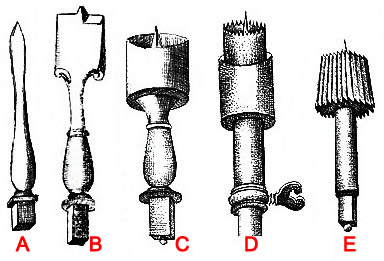

Trepan Blades, The French Chirurgerie, Jacques Guillemeau (1598)

The real key to a trepan and a trephine was the blade. In modern terms the round blades that cut through bone would have been called trepans while the tool they were mounted into would be called either a brace- or T-handle. As noted, the terminology of the time was different.

Five different types of trepanning blades are shown in books from around this period, seen in the image at left. They include:

A - Piercer Blade

B - Exfoliative Blade

C - Knife Crown Blade

D - Serrated Crown Blade with Cap

E - Tapered Blade

Let's look at each of them.

A - Piercer Blade

Piercer blades are not truly trepanning blades, but were used to create a small perforation in the skull. This

Piercer Blade in Brace Trepan, Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical

operations (1708)

would then act as a pilot hole to guide the pin located in the center of the other blades as they bored through the bone. French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis explained that the surgeon "mounts the Piercer... and turning it five or six Rounds, he makes a small Orifice the depth of a half Line, or the four and twentieth Part of an inch, which serves to lodge the Point of his Pyramid, and so to conduct the Crown [of the round trepans], that it shall not Waver either on one side or the other."1

B - Exfoliative Blade

Scaling Blades on Trepan,

Ambroise Paré (1649)

Exfoliative blades were used to make holes in the skull. Unlike the other trepan blades discussed here, they were not hollow in the center, but were flat cutting edges all the way across with a pointed center pin which was used to guide the blade.

Ambroise Paré calls this a scaling or desquamatory blade. He explained that they were used when a "contusion goes but [only] to the second Table [of the skull], or scarse so far; the baring or taking away of the bone, must go no further than the contusion reaches; for that will be sufficient to eschew and divert inflammations and divers other symptomes."2

According to Paré, the key is that this blade was only used when the surgeon did not intend to fully pierce the skull. Paré explains that the blade will "easily take up as much of the bone, as you shall think expedient"3.

Fellow French surgeon Dionis has a much different opinion of the exfoliative blade as a trepanning tool. He warns that it "ought not to be used; I don’t know who could have invented it; but that way of piercing the Bone by scraping it, and raising several leaves [of bone] one after another, must very much shock the Head, and do more Mischief than Good."4 He goes on explain the very real risk of damaging the dura-mater and brain with the sharp center pin if the surgeon mistakenly drills too deeply because "we have not the Liberty of taking it [the pin in the center] out as we do the Needle in common Trepans."5

C - Knife Crown Blade

Knife crown blades have a round hollow blade with a sharpened edge. They are guided by a sharp pin in the center. Jacques Guillemeau explains that such a trepan "onle cutteth the fleshe: & is verye necessarye whe[n] we must suddaynlye trepane, becaus we fear any greate fluxio[n]s of bloode."6 He goes on to say that it "must cut as wel as a Kinfe [knife]" because it is used to cut through the 'musculouse fleshe of the Heade' after the area has been cauterized.7 Guillemeau is the only author under study to show this blade, so it does not appear to have been commonly used. This may be due to the difficulty of healing round wounds, something English military surgeon Richard Wiseman specifically warns against.8

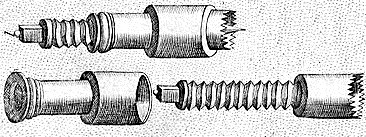

D - Serrated Crown Blade with Cap

The crown blade is a round, hollow blade with a serrated edge and a sharp pin in the center to guide the tool.

Crown Blade With Cap - Assembled and Separate, The French Chirurgerie,

Jacques Guillemeau (1598)

Guillemeau states that it is this tool which should be properly called a trepan.9 One drawback to the crown blade is that the sharp sides of it were straight, which meant that the blade could easily slip down once the teeth broke through the skull causing damage to the dura mater and the brain. To remedy this, a cap was added to the assembly to restrict the cutting depth. The cap forms a ledge which prevents the crown blade from going any deeper than the depth at which the cap is set. In Guillemeau's image of the crown blade with cap (seen at right), the inside of the cap (lower right) was threaded so that its position could be set on the threaded screw shaft of the crown blade (lower left).

Crown Blade With Screw Fastened Cap, the surgions mate, John Woodall (1639)

In his book, sea surgeon John Woodall shows a different style of of this trepanning blade which has the cap being secured on the shaft of the crown blade using a thumb screw. Later in the book, he noted that this style of blade "was very apt on the suddaine to slip downe upon the (Dura Mater) by error and improvidence of the Artist, either upon oblivion or omission divers wayes, as namely for one, if the Artist did not truly, equally, and strongly fasten the small screw, being an iron or rather a steele pin, that stayeth and fasteneth the said head [cap] of the Trapan"10. So he developed an improved trepan blade.

The center pin has been mentioned several times, but it should be reiterated that this sharp needle could be removed from the blade. Pierre Dionis explained that as the teeth of the crown blade began to bite into the bone of the skull to the extent where they were "sufficient to guide the Instrument without the Pyramid [guide pin]", it should be removed lest it "(not without great Danger)... prick the Dura-Mater, if we forget to take it out."11

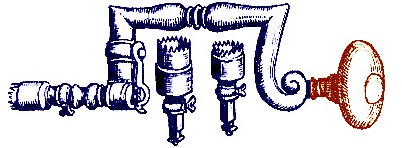

E - Tapered Blade

Because of the dangers Woodall mentioned when using the crown blade with cap, he developed

Tapered Blade, , the surgions mate, John Woodall (1639)

the Tapered Blade. He put it on his traphine, explaining that "the heads of the Trafine are made all taper, to wit, wider above then beneath, and also cut both ways, and cannot therefore easily be said to offend the (Dura Mater) by an error ...in the use thereof, without stupid ignorance in the Artist."12

Following its creation, this type of blade seems to have eventually replaced the crown blade with cap. By 1690, the beginning of the golden age of piracy, nearly all the surgeon's books under study show tapered blades. As if to verify its presence even at sea, sea surgeon John Atkins explained that the tool was prevented from cutting into the dura mater "by the Diameter [of the blade] enlarging upwards"13.

Purmann (1706) |

Tapered Blade on Trephine, Johannes Scultetus (1666) |

Tapered Blades on Trephine, Paul Barbette (1687) |

Like its predecessor, the tapered blade had a sharp guide pin in the center to keep the blade fixed while the surgeon turned the handle of the instrument. It was similarly removed once the teeth of the round blade started cutting into the bone of the skull.

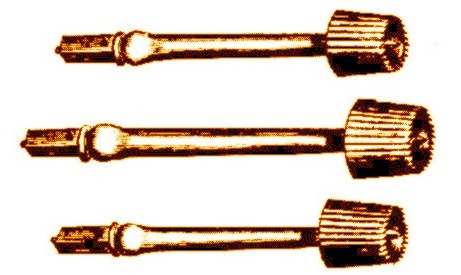

Blade Size

In addition to mentioning the different blade types, several surgeons

Tapered Blade Sizes, the surgions mate, John Woodall (1639)

discussed the importance of blade diameter with regard crown and tapered blade trepans. Before the introduction of his tapered trepanning blade in 1617, John Woodall advised his readers not "to use the greatest head of the Trapan, which hath commonly 3 or 4 heads: for if nature onely have a breathing it will wonderfully helpe it selfe by purging the contused blood through the orifice, by way of matter or excrement."14 Although his wording is is a bit muddled, Woodall is suggesting that a smaller blade can work just as well as a larger blade when opening a contused wound to relieve pressure on the brain.

After he introduced the tapered blade, he explained that the surgeon would have "three heads of severall sizes in readinesse by him [which] is... very fitting"15.

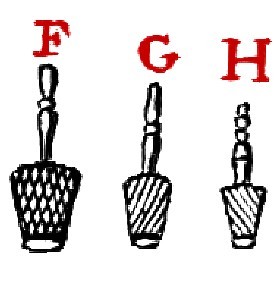

Tapered Blade Sizes, A course of chirurgical

operations, Pierre Dionis, (1708)

French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis also made a point of noting the use of different sizes of trepanning blades. "The Chirurgeon must begin with the Choice of the Crown [tapered blade] which he intends to use; wherefore I shew you three of different Sizes, the larger F, the middle one G, and the little one H, and being determin’d by the Nature and Figure of the Wound it self, he pitches on [chooses] that which is most convenient"16.

Dionis later proposes the question, "which of these three is to be us’d, and what quantity of Bone is to be taken out." He answers "that generally the least is to be preferr’d, because the Brain ought to be as little uncover’d as possible, and a great Aperture is most difficult to cure"17. However, he does suggest that the largest is sometimes best, particularly when the patient is having seizures, because "‘tis better to make use of it, than to be obliged to perform two Trepannings with the little one."18

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 3rd ed., 1733, p. 283-4; 2,3 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.269; 4 Dionis, p. 279-80; 5 Dionis, p. 280; 6,7 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, 1597, not paginated; 8 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1676, p. 279; 9 Guillemeau, not paginated; 10 Dionis, p. 284; 11,12 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639, p. 314; 13 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 86-7; 14 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 5; 15 Woodall, 1639, p. 316; 16 Dionis, p. 280; 17,18 Dionis, p. 283

Cutting Bone: Trepans and Trephines - Bone Dust Brush

A small brush was sometimes used to sweep away the bone dust and small slivers

Bone Brush, A course of chirurgical

operations, Pierre Dionis, (1708

of bone created during the trepanning process, although it's adoption appears to have occurred during the middle/late time of the golden age of piracy. Instrument historian John As Kirkup explains, in "the eighteenth and

Samuel Mihles (1746)

nineteenth centuries, many skull-trephining instrument boxes contained a bristle brush to clear bone dust from the clogged teeth of cylindrical saws"1.

The first mention of a trepanning brush in the surgical books under study comes from French surgeon Pierre Dionis. He shows one in the 1708 edition of his book Cours d'Operations de Chirurgerie. In agreement with Kirkup's statement, Dionis notes that during trepanning the surgeon should "withdraw the Crown [from the skull] to clear it of the Saw-Dust and Blood with the little Brush N; and before we fix it on again"2.

John Atkins is the only sea surgeon to mention the use of the brush. Atkins wrote primarily about his experiences in the early 1700s, which In agrees with the notion that brushes came into use later in the golden age of piracy,. He suggests the surgeon "clean it [the trepan], and the Skull from Dust with a little Feather-Brush"3

1 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, 2005, p. 78;2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 3rd ed., 1733, p. 284; 3 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 87

Head Surgery Tool Kits

It is appropriate to end the discussion of head surgery tools with a brief discussion of trepanning tool kits since these encased, often luxuriously

Photo: Steffen Habermann

An Extensive German Head Surgery Kit,

German

National

Museum, Nuremberg (~1750)

packaged sets of neurological instruments incorporated many of the tools that have been discussed. There is not a lot of information about the early history of trepanning kits sold by surgical instrument or cutlery manufacturers. This is complicated by the fact that most instrument manufacturers didn't 'sign' their instruments during the golden age of piracy. Since it cannot usually be said who made instruments used during the golden age of piracy, accurately dating them is rather challenging.

Most head surgery sets I have seen were produced after 1750. The oldest example of a such a kit that I have come across is on an antiques website. There, Dr. Douglas Arbittier identifies a set there as being "a very rare cased set by [Edward] Stanton, an English instrument maker... actively producing instruments in 1738".1 This kit features an elevator, lenticulars, a bone dust brush and a trephine with a piercer and two tapered blades. (You can see it here.)

Since the end of the golden age of piracy is defined here as 1725, this kit is at least a decade late. This is not to say that there were no head surgery sets available during the golden age of piracy, just that I haven't found evidence of any yet.

It is also questionable whether a sea surgeon, who was typically not as well paid as his land-based brethren, would have been able to afford such an extensive set if it were available. The majority of

Trephination Set,

Wellcome Collection (1771-1800)

surgical instruments provided to sea surgeons appear to have been purchased as a large set in preparation for a ship's voyage. (Although some sea surgeons, particularly those who had some experience and were traveling on merchant, rather than naval, ships, bought their own instruments.)

In introducing a book on the topic William Fabry explains

Therefore that Generals may understand what things are most necessary to furnish a Chest with, I though good to set down both the principal Medicaments, and Instruments, that a Chirurgeon, following the Camp or Sea, ought to be provided with; and if there should be occasion for any others [not provided], he may furnish himself at the next Shop he comes at.2

John Moyle refers to storing medical supplies in two chests in his book. He warns his reader that "in the forming of your invoyce [of medical materials for going to sea] you must consider that you have no more room than only a Chirurgery Chest, and Drug Chest to contain all your things; therefore you are not to carry greater variety than of necessity you must."3 Moyle later also refers to a dressing box "with 6 or 8 Partitions in it, and a Place for Plaisters ready spread"4 that may have contained other instruments, although they would not include tools for head surgery.

Moyle's comments hint that there would not be room enough for multiple boxes and individual sets of instruments such as trepanning kits. Since all his tools would have to be stowed in the boxes for which the sea surgeon had room, it is unlikely that he would have had such a set.

1 Douglas Arbittier, "Neurosurgical Antiques", medicalantiques.com, gathered 11/19/15; 2 Guliielm. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 2674, p. 9; 3 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 4; 4 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 46