Head Surgery Tools Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Head Surgery Tools From the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Cutting Bone

Cutting the Skull,

Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous

Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, frontispiece (1649)

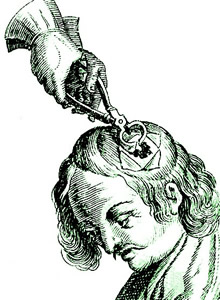

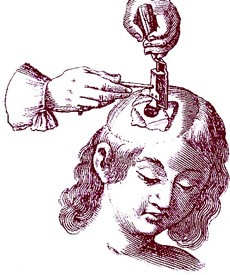

Trepanning - the operation of boring holes in the skull - was an operation with a high mortality rate. The tools used to operate on the skull were referred to as 'capital tools' (along with the some of the tools used in amputation) which was done to indicate the high fatality rate associated with such operations. (One definition found in Samuel Johnson's dictionary for 'capital' is "That which affects life."1)

When talking about tools used for working on the skull, sea surgeon John Moyle warned his readers to "be cautious how you use your capital Instrument (as Raspitory, File, Saw, or the like) with them, and great care you may do good"2.

We have already seen how a few tools were also used to 'cut' the skull including knives and scraping tools such as chisels, rasps, and lenticulars. Only a couple of instruments are discussed which were specifically used to cut the skull during the golden age of piracy. These include bone cutting forceps, head saws, trepans and trefines.

1 Samuel Johnson, "Capital", A Dictionary of the English Language, 3rd ed., 1768, not paginated; 2 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 51

Cutting Bone: Bone Cutting Forceps

(Cutting Mullet, Forsex, Cutting Pincers, Tongs, Parrot's Bill Cutters)

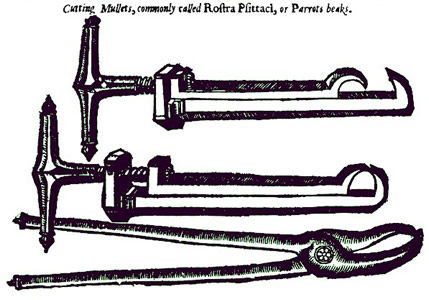

Forceps were a relatively simple way to cut bones when they could be used. There are two different kinds of bone cutting forceps described in the period medical books: a manual pair, which were operated like normal forceps, and a screw-driven pair which would have allowed more force to be applied to the operation by turning the screw.

Bone Cutting Forceps,

Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous

Chirurgion Ambrose

Parey, p. 269 (1649)

Ambroise Paré comments "if there be a space [in an existing wound] so large, as that the ends of those mullets [cutting forceps] may enter, you may easily shear off so much of the bone as shal be necessary and requisite for the taking away of these scales [splintered pieces of bone in the skull], without any assistance of the Trepan, which I have done very often and with good success; for the operation performed by these mullets is far more speedy and safe, then that with the Trepan, and in the performance of every operation, the chief commendation is given to safeness and celerity [speed]."1

Paré does not go on to detail about the methods for using such tools, although he does provide a figure of the screw-operated tool in the open and closed position and the manual tool, as seen here. Like Paré, protege Jacques Guillemeau shows images of both types of bone cutting forceps. His images are very similar to Paré's and his descriptions add little new information about the tools, so they are not included here.

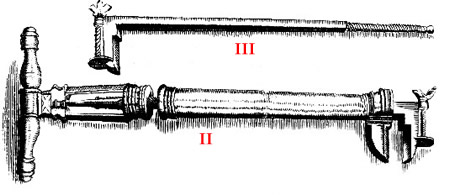

Parrot's Bill Forceps with Depth Screw, l'Arcernal de Chirurgie, Johannes Scultetus (1665)

German surgeon Johannes Scultetus shows a screw-operated bone cutting forceps with an interesting refinement that Paré and Guillemeau do not show.

Fig. II is a pair of pincers to cut out [bone] with a Parrats beck [parrot's beak] upon which is fastned a screw with a broad head, which will not suffer the bill to go in so far as the dura mater, (for I use it in fractures of the skul)... Fig. III is a Parrats bill out of its socket that the Artist may more plainly see the screw of the bill.2

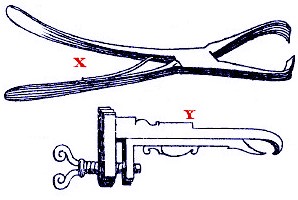

Bone Cutting Forceps, Pierre Dionis, A course of

chirurgical

operations (1708)

Writing about a century after Paré and Guillemeau, fellow French surgeon Pierre Dionis explains that when "there are some Points of the Bones elevated outwards, some [surgeons] order them

Using Bone Cutters, l'Arcernal de Chirurgie,

Johannes Scultetus (1665)

to be cut off with the incisive Forsex [probably meaning 'Forceps'] X, and if we cannot attain our end with that Instrument, then we take the other Forsex Y, which goes with a Screw, and will infallibly cut them, by reason a Screw may exert beyond Comparison more force than a Hand."3

However, just as he noted with regard to using chisels on the skull, Dionis says that he 'doesn't approve of' cutting forceps. His concern is that the chips of bone may be driven into the dura mater as they are being cut off, causing trauma to the patient's brain. He closes his argument noting "If I have recited to you these old Operations, ‘tis not to advise, nor wholly dissuade the use of them, but only to lay before you the several Sorts of Practice, that you may determine which are to be follow’d or rejected on several Occasions."4

None of our sea surgeons discuss the use of bone cutting forceps on the skull.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.270; 2 Johannes Scultetus, The Chyrurgeons Storehouse, 1674, p. 11; 3,4 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1710, p. 277

Cutting Bone: Head Saws

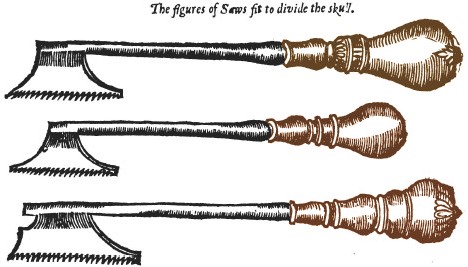

Head Saws, Chirurgiae Universalis Opus

Absolutum, Giovanni Andrea della Croce (1573)

Head saws date back to the early history of trepanning - the tic-tac-toe pattern cut into the skull to remove the square piece in the center would have been made with them.

In the fourteenth century, a curved blade came into use1, probably to allow targeted cutting of bone fragments from an existing head wound. In his 1573 book, Giovanni Andrea della Croce shows six such blades. However, most of the books under study show head saws having a straight blade.

Skull Saws,

Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous

Chirurgion Ambrose

Parey, p. 266 (1649)

Ambroise Paré suggested the use of head saws when "the bone is not totally broken or deprest, but only on one side"2. He advised the surgeon "to divide the skul with little saws like these, which yee see here expressed; for thus so much of the bone, as shall be thought needful, may be cut off without compression, neither will there be any danger of hurting the brain or membrane with the broken bone."3

Paré's compatriot Jacques Guillemeau also discusses a bone saw, although his is just one part of a set of other head surgery instruments. It appears to be smaller than the three figured by his mentor. Guillemeau also suggests a much smaller role for the tool which he explains "only serveth, to sawe throughe the bones of the Heade."4

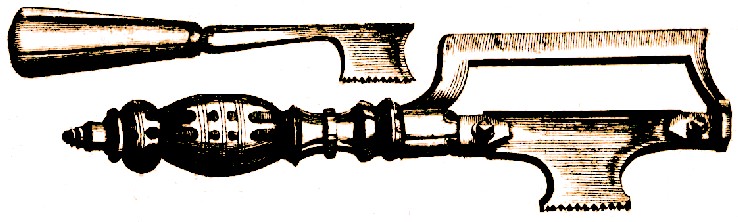

German surgeon Johannes Scultetus shows two 'straight saws' "with which some men cut away the distances between the holes made in the skul with the Trepans, and abolish rifts like hairs that do not penetrate, and scrape away the rottenness of the cranium."5 One of Scultetus' saws is fairly similar to those shown by Paré and Guillemeau, but the other is rather unique in that it appears to be a small projected saw blade mounted in a bone saw handle.

Artist: Jonas Arnold Delineavi - Skull Saws, Armamentarium Chirurgicum Bipartitum,

Johannes Scultetus (1666) Artist: Jonas Arnold Delineavi - Skull Saws, Armamentarium Chirurgicum Bipartitum,

Johannes Scultetus (1666)

|

Turning Saw, Armamentarium Chirurgicum Bipartitum,

Johannes Scultetus (1666)

For cutting the space between multiple trepan holes (which in itself is an unusual operation not mentioned by other surgeons) Scultetus recommends a 'turning saw' which he invented.

It is a "little saw provided with two wheels with teeth"6. By turning the handle sticking out of the side of the tool, a series of interlocking gears

Using Bone Cutters, l'Arcernal de Chirurgie,

Johannes Scultetus (1665)

cause the saw blade at the bottom to move back and forth.

Scultetus explains that the need to cut out this material between trepanned holes "have not space sometimes, there is need that two or three holes be made in the skul with Trepans, the distance between them is cut forth with this small saw, without any danger of hurt, whereby the Levitator [elevator] may be the more commodiously put down, and the small peece of bone, which oft-times pricks the membranes, may be taken forth."7 Interesting though his gear-driven design is, it would have been unwieldy, requiring two hands to operate. This saw doesn't appear in the other surgical manuals under study and it is unlikely that most sea surgeons would have used such a tool.

Sea surgeon John Woodall actually has quite a bit to say about head saws as an alternative to trepans, although he does not suggest they be used to create a new hole like Scultetus. He only uses head saws to expand the existing rift in the skull.

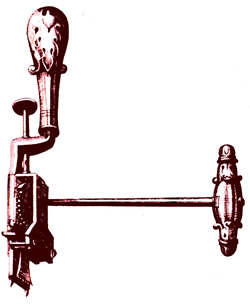

Head Saw, John Woodall

the surgions mate (1639)

The Head-sawe is an instrument with which a vent may be given sometimes through the Cranium, and thereby the use of the Trapan [trepan] may be happily forborne: & for that reason this instrument may have a place in the Surgeons Chest; sometimes also a small ragged peece of the Cranium may so hang, that this instrument may bee used to sawe it away.8

However, he follows this with yet another warning to his inexperienced surgical readers.

But I wish young Artists not to bee over-busie in sawing, plucking away, or raising the fractured Cranium, as it is said, more then of meere necessitie they are urged unto, lest fearefull and soddaine accidents follow not to be avoided nor stayed: If ought be meerely loose, and in sight, take that away; if not, forbeare to plucke much or force [pieces of bone off], for nature is exceeding beneficiall in electing [picking out] unnaturall things in that part, and very froward [difficult to deal with] if thou use force whilest shee is weake her selfe.9

The head saw Woodall figures in his 1639 book is curved like those shown by Andrea della Croce. It is remarkably similar in some ways to the curved edge of the saw made popular by surgeon William Hey in the early nineteenth century.

Head saws seem to have fallen out of use before the beginning of the golden age of piracy, however. Woodall's saw last appears in the fourth edition of his book published in 1655. Historian Charles Thompson points to the saw drawn by Scultetus in a book published in 1674 as the being one of the last recommendations for this tool before the golden age of piracy began. "From this period the head-saw appears to have fallen into disuse for over a century, until in 1783 it was revived by Cockell, a surgeon of Pontefract [England]"10. None of the later sea surgeons active during the golden age of piracy show or discuss a head saw in their books.

1 Charles John Samuel Thompson, The History and Evolution of Surgical Instruments, 1942, p. 56; 2,3 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.268; 4 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, 1597, not paginated; 5 Johannes Scultetus, The Chyrurgeons Storehouse, 1674, p. 14; 6,7 Scultetus, p. 13; 8,9 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 7; 10 Thompson, p. 57