Halloween - Pompions and Ghostly Tales: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Pompions, Monsters and Ghosts in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Mermaids

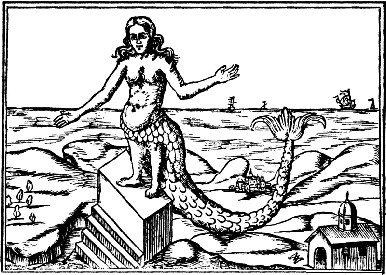

Derceto, from Athanasius Kircher's Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652) According to Wikipedia, tales of mermaids first appeared in Assyria in 1000 BC. A goddess by the name of Atargatis accidentally killed a shepherd by making love to him. She was so ashamed that she decided to go jump in the lake. (Seriously. I can't make this sort of thing up.) There she took on the form of a fish but the legend says her beauty showed through her fishy appearance causing her to take the form of a mermaid.1

From this came several variations on the Atargatis legend, such as the Greek myth of Derceto. She fell in love with a young man and and mothered a child, which caused her such shame that she flung herself into a lake where her body was changed into the form of a fish though her head remained human.2

But that is all ancient history. Let's focus on material in and around the golden age of piracy.

Mermaids In the Encyclopedia

The 1797 Edinburgh Encyclopædia britannica (subtitled 'A dictionary of arts, sciences, and miscellaneous literature') has much to say on the topic of mermaids. The entry begins by noting that "[h]owever naturalists may doubt of the reality of mermen or mermaids, we have testimony enough to establish it; though, how far these testimonies may be authentic, we cannot take upon us to say."3 They follow with several accounts of mermaids and mermen, most of which pointedly note the creatures inability to speak.4 The account of most interest to our purposes features a 16th century physician:

In the year 1560, near the island of Manar, on the western coast of the island of Ceylon, some fishermen brought up, at one draught of a net, seven mermen and mermaids; of which several Jesuits, and among the rest F. Hen. Henriques and Dimas Bosquez, physicians to the viceroy of Goa, were witnesses. The physician, who examined them with a great deal of care, and made dissection thereof, asserts, that all the parts both internal and external were found perfectly conformable to those of men. See the Hist. de la compagnte de Jesui, P. II. T. IV. N° 276. where the relation is given at length.5

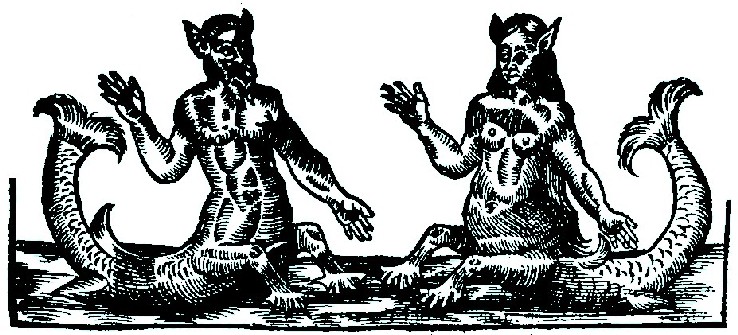

A Triton and a Siren of Nilus from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgion Ambroise Parey, p. 664 (1649) |

Although he never saw any, the famous 16th/17th century French surgeon Ambroise Paré does mention mer-people in his writings. He talks about Tritons, "which from the middle upwards are reported to have the shape of men."6 He also mentions the "Sirenes, Nereides or Mermaids, who (according to Plinie) have the faces of women, and scalie bodies; yea, where as they have the shape of man"7. Paré puts his faith in the reports of Pliny. He specifically asserts that mer-people are not some result of cross-specie procreation, rather "they consist of their own proper nature"8 and so must be entities unto themselves.

Mermaids, Women Fish and Dugongs

When scientists go looking to explain what people in the past thought were mermaids, they often point to Dugongs and Manatees. Mermaid aficionados often protest that they look nothing like people and so writing off historical accounts of mermaids as having been a case of mistaken identity is unfair. However a closer look at some of the actual descriptions given by those who saw them tend to suggest otherwise.

One of the more famous accounts of mermaids come from an entry in Christopher Columbus' Journal, written when he was near Hispaniola. On January 9th, 1493, it reports, "On the previous day, when the Admiral [Columbus] went to the Rio del Oro, he saw three mermaids, which rose well out of the sea; but they are not so beautiful as they are painted, though to some extent they have the form of a human face. the admiral says that he had seen some, at other times, in Guinea [the western African Coast], and on the coast of Manequeta."9

Photographer: Julien Willem

Surely You Can See the Appeal Here? Closer to the golden age of piracy, we have an account from a friar. While visiting a town near Lake Nauján, on the island Mindoro in the Philippines, Domingo Navarrete mentions a fish "commonly call'd Piscis Mulier, or Woman-Fish" which he noted had "a singular virtue against Defluxions [Fluxes]"10. While he was visiting there, the curates of Nauján told him about these creatures.

An Indian going a fishing every day, found near the Water a Piscis Mulier, which they say is like a Woman from the Breasts downwards. He had actual Copulation with her, and continu'd this beastly Whoredom for above six Months, without missing a day. At the end of this time God mov'd his Heart to got to Confession; he did so and was commanded to go nor more to that place, which he perform'd and that abomination ceas'd. I own, that if I had not heard it my self from the Person I have nam'd, I should have doubted of it.11

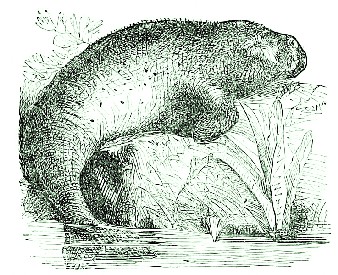

The editor of Navarette's narrative explains that the Piscis Mulier is today called a Dugong, which will make this account seem doubly amazing when you look at the photo.

While

A Dugong Climbing Onto Land, from

Popular Science Monthly,

Vol. 20 (1881-2) not actually having seen a mermaid himself, Captain Nathaniel Uring relates a story of one told him by a priest who claimed to have seen one. He explains that "...in the Lake of Matamba are found Fish much like Men and Women in Shape, and that the Queen of that Country caused one of them to be taken in a Net, to convince the Father of the Truth of it, he doubting before he had seen it, believing it to be Stories devised by the Negroes; that which they took was a Female, big with young, which he describes thus; the Colour was Black, it had long Hair, and large Nails upon long Fingers, and differ'd nothing from humane Kind but want of Speech; it lived Twenty-four Hours before it was taken, and then died."12

The priest goes on to explain that mermaids are found in the 'River of Zair' [the Congo],

which from the Middle upwards has some Resemblance of a Woman; it has Breasts, Nipples, Hands, and Arms, but downwards it is altogether Fish; its Head is round, and the Face like that of a Calf, a large ugly Mouth, little Ears, and round full Eyes; that he has eat of them divers Times, and it tastes not unlike Swine's Flesh, and the Entrails resemble that of a Hog, for which Reason the Natives Name it Ngullin a-Masa (the Water Sow;) but the Portugueze call it Peixe Molker (the Woman Fish;) although it feeds on Herbs which grow on the River Side, yet it does not go out of the water, but only holds its head out when it feeds: They are taken for the most Part in the rainy Times, when the Waters are disturbed and muddy, and cannot discern the Approach of Fishermen; they are caught by striking. This Creature that the good Father speaks of as the Mermaid, can be no other than the Manatee, it answering exactly to that Description, only he has made the Finns to be Hands and Arms.13

The first description of these startling sea creatures is vague, but the second uses the term 'woman fish', again referring to dugong. It may also have been an African manatee which have been found in the Congo.

The Figure of a Dugong, From On the Genesis of Species, by St. George Mivart, p. 71 (1871) |

Manatees

A West Indian Manatee (NASA)

Manatees are often accused of confusing sailors by those seeking to disprove the existence of mermaids. We find relatively few accounts recounting the discovery of mermaids or mermen from the golden age of piracy. The ones we have seen suggest that these creatures are not much like the beautiful half fish/half human creatures that we think of today, having only some similarities to human form and being bereft of speech. So even period reporters seem to suspect that what they were seeing were not mer-folk.

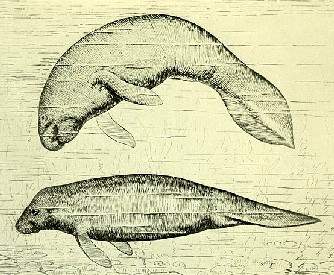

Many period authors talk about manatees and several sailor accounts from around this period positively identify manatees as being uniquely such, quite distinct from mermaids. Although they don't generally come to mind when considering Halloween, let's continue the mermaid discussion by taking a closer look at how period and near-period authors viewed these counterfeit mer-creatures.

Artist: Henry W. Elliot

Manatees, from Favorite Fish and Fishing, (1908)

Naval surgeon John Atkins gives a pretty accurate description of West Indian manatees. He explains that they are "about eleven or twelve Foot long, and in girt[h] half as much; Teeth only in the back part of her Mouth, which are like the Ox’s, as is also her Muzzle and Head; with this difference, that her Eyes are small in proportion, and Ears you can scarce thrust a Bodkin in; close to her Ears almost, are two broad Finns, sixteen or eighteen inches long, that feel at the Extremities as tho’ jointed; a broad Tail, Cuticle granulated, and of a colour and touch like Velvet: the true Skin an Inch thick"14.

Captain Nathaniel Uring reported that they are found off the coast of Honduras.15 Privateer and ersatz naturalist William Dampier reports seeing them in Mindanao, although he explains that they "are not near so big as those in the West-Indies. The biggest that I saw would not weigh above 600 Pound"16. Dampier most likely confused a dugong with a manatee.

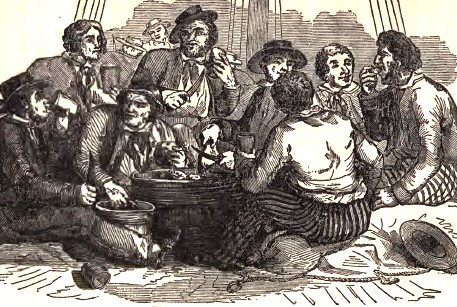

Perhaps

Artist: Robert Billings

Sailors Dining on Deck, From The American Cruisers' Own Book.

by Capt. George Little, p.45 (1849)

the most extraordinary thing about manatee to the modern reader is how they were used during this period - as food. Dampier reported that "the flesh both of the Turtle and Manatee are very Sweet."17Uring praised it highly. "The Flesh of it was as white as the finest Veal, and something like it in Taste. This Creature is not at all like a Cow, tho’ it is so call’d [he refers to it earlier in his narrative as 'Sea-Cow']; and I am ready to think it had its Name from the Taste of the Flesh, which eats more like Beef than Fish."18 John Atkins likewise explains that manatee flesh "cuts fat, lean, and white like Veal: Boiled, stewed or roasted (for I have eaten it all ways) it has not fishy Taste, but is as acceptable a Treat as Venison to Cockneighs [Cockneys]."19 Later, while at Sierra Leon, Atkins notes that the manatee served there was "white, and not fishy; but very tough, and seasoned high (as are all their Dishes) with Ochre, Malaguetta, and Bell-Pepper."20

1 Mermaid, wikipedia, gathered 10/6/13; 2 Ibid; 3 Mermaid, Encyclopædia britannica: or, A dictionary of arts, sciences, and miscellaneous literature, Volume 11, Ediburgh, p. 405; 4 Encyclopædia britannica, p. 405-6; 5 Encyclopædia britannica, p. 406; 6 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 676;, p. 664; 7 Paré, p. 676; 8 Paré, ibid. , 9 Christopher Columbus, Journal of the First Voyage of Christopher Columbus, American Journeys Collection, p. 218; 10 Domingo Navarrete, The Travels and Controversies of Friar Domingo Navarrete 1618-1686, p. 40; 11 Navarrete, p. 40-1; 12 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, p. 242; 13 Uring, ibid.; 14 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 42-3; 15 Uring, p. 243; 16 William Dampier, Memoirs of a Buccaneer, Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World -1697-, p. 221; 17 Dampier, ibid.; 15 Uring, p. 169; 19 Atkins, p. 43; 20 Atkins, p. 55

"Of Monsters and Prodigies" - Sea Monsters

In the almost 50 pages of monsters and prodigies included in his surgical works, French surgeon Paré gives a great deal of attention to sea creatures. Unlike some of the other monsters he talks about, Paré suggests that these are not quite so 'wonderful of themselvs' because they "consist of their own proper nature, and that [they are] working well and after an ordinarie manner; yet they are wondrous to us, or rather monstrous, for that they are not verie familiar to us."1 He explains that this is particularly true "in the Sea, whose secret corners and receptacles are not pervious to men"2.

A Monk Fish, from The Workes of

That Famous

Chirurgion Ambroise

Parey, p. 677 (1649)

With that introduction he devles into his store of tales from other authors, often providing wonderfully gruesome drawings of the creatures being described.

As with the discussion of Paré's land-based monsters, I will primarily defer to his descriptions concerning the sea-based monsters. It is quite readable, although I have added a few paragraph breaks and a comment here.

A Bishop Fish, from The

Workes of That Famous

Chirurgion Ambroise

Parey, p. 677 (1649)

"In our times, saith Rondeletius, in Norway, was a monster taken in a tempestuous sea, the which as manie saw it, presently termed a Monk, by reason of the shape of which you may see set forth [at right].

Anno Dom. 1531. there was seen a sea-monster in the habit of a Bishop, covered over with scails: Rondoletius and [Swiss naturalist Conrad] Gesner have described it.

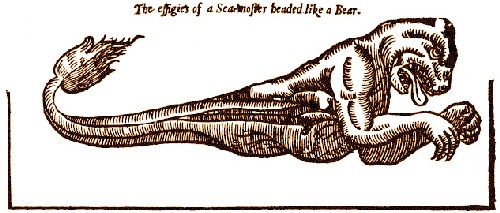

Gesner professeth that hee received from Jerom Cardane this monster [below right], having the head of a Bear, the feet and hands of an Ape."3

The Bear-headed, Ape-handed Sea Monster, from The Workes of

That Famous

Chirurgion

Ambroise

Parey, p. 677 (1649)

The Sarmatian, or Eastern Germane Ocean contain's fishes unknown to hot countries, and verie monstrous. Such is that which resembling a snail, equal's a barrel in magnitude of bodie, and a stag in the largeness and branches of her horns: the ends of her horns are rounded as it were into little balls, shining like unto pearls, the neck is thick, the eies shining like unto little candles, with a roundish nose set with hairs like to a cat's, the mouth wide, whereunder hang's a piece of flesh verie uglie to behold. It goe's on foure legs, with so manie broad and crooked feet, the which with a long tail, and variegated like a Tiger, serv's her for fins to swim withal.

This creature [below] is so timorous, that though it be an Amphibium, that is, which live's both in the water and ashore, yet usually it keep's it self in the sea, neither doth it com ashore to feed, unless in a verie clear season. The flesh thereof is verie good and greateful meat, and the bloud medicinable for such as have their

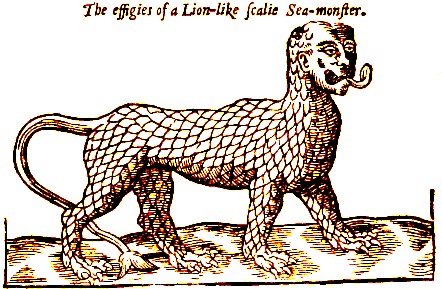

The Scaly Lion Sea Monster, from The Workes of

That Famous

Chirurgion

Ambroise

Parey, p. 677 (1649)

livers ill affected, or their lungs ulcerated, as the bloud of great Tortoises is good for the Leprosie, Thevet in his Cosmographie affirmeth that hee saw this in Denmark."4 [Sorry, there is no picture of this creature, but the description was too interesting to leave out.]

"Not long before the death of Pope Paul the third, in the mid'st of a Tyrrhene sea [in the Mediterranean Sea], a monster was taken, & presented to the successor of this Paul: it was in shape & bigness like to a Lion, but all scalie, and the voice was like a man's voice. It was brought to Rome to the great admiration of all men, but it lived not long there, beeing destitute of it's own natural place and nourishment, as it is reported by Philip Forrest."5

"Anno Dom. 1523. the third daie of November, there was seen at Rome this sea-monster [below left], of the bigness of a childe of five years old, like to a man even to the navel, except the ears; in the other parts it resembled a fish."6

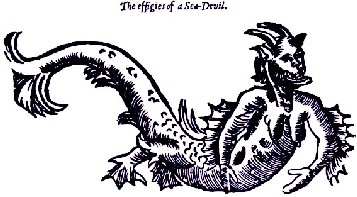

"Gesner make's mention of this Sea-Monster [below right], and saith that hee had the figure thereof from a Painter, who took it from the verie fish, which hee saw at Antwerp. The head look's verie ghastly, having two horns, prick-ears, and arms not much unlike a man, but in the other parts it was like a fish. It was taken in the Illyrian Sea, as it came ashore out of the water to catch a little childe: for being hurt by stone cast by fisher-men that saw it, it returned a while after to the shore from whence it fled, and there died."7

A Sea Monster, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgion Ambroise Parey, p. 678 (1649) |

A Sea Devil, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgion Ambroise Parey, p. 678 (1649) |

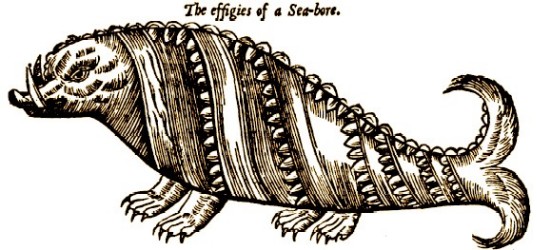

The Sea Bore, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgion Ambroise

Parey, p. 679 (1649)

"This great monster [at right] was seen in the Ocean-sea, with the head of a Bore, but longer tusks, sharp and cutting, with scails set in a wonderful order, as you may see by this figure.

Olaus Magnus writes that this monster [seen below left] was taken at Thyle an Island of the North, Anno Dom. 1538. it was of a bigness almost incredible, as that which was seventie two foot long, and fourteen high, and seven foot between the eies: now the liver was so large that there with they filled five hogsheads, the head resembled a swine, having as it were a half-Moon on the back, and three eies in the mid'st of his sides, his whole bodie was scalie.

The Sea-Elephant, as Hector Boëtius write's in his description of Scotland; it is a creature that live's both in the water and ashore, having two teeth like to Elephants, with which as oft as hee desire's to sleep, he hang's himself upon a rock, and then hee sleep's so soundly, that mariners seeing him at sea, have time to com ashore and to binde him, by casting strong ropes about him. But when as hee is not awaken'd by this means, they throw stones at him, and makes a great nois; with which awakned, he endavour's to leap back into the sea with his accustomed violence, but finding himself fast, hee grow's so gentle, that they may deal with him as they pleas. Wherefore they then kill him, take out his fat, and divide or cut his skin into thongs, which because they are strong and do not rot, are much esteemed of."8

The Sea Swine, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgion Ambroise Parey, p. 679 (1649) |

The Sea Elephant, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgion Ambroise Parey, p. 679 (1649) |

A Sea Calf, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgion Ambroise Parey, p. 678 (1649)

"Olaus Magnus tel's that a Sea-monster taken at Bergen, with the head and shape of a Calf, was given him by a certain English Gentleman. The like of which was presented lately to King Charls the ninth, and was long kept living in the waters at Fountain-Bleau, and it went oft-times ashore. This is much different from the common Sea-calf or Seal."9

In a side note to the image of the sea-calf (which he also refers to as a 'sea Mors') Paré explains that he believes "the sea-Bore and Elephant to bee the same [creature] noting that it "taken commonly by our men in their Greenland voyages"10. This could be any number of sea animals including a dugong, a manatee or possibly even a narwhal. (Of the three, the narwhal is the only animal found near Greenland, although it has a large horn that would most likely have been noticed by the authors of the original descriptions.)

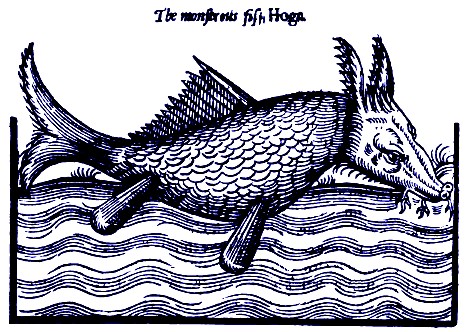

Hoga Fish, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgion Ambroise

Parey, p. 681 (1649)

"In a deep lake of fresh water, upon which stand's the great cittie or town of Themistitan, in the Kingdom of Mexico, which is built upon piles, like as Venice is, there is found a fish of the bigness of a calf, called by the Southern Salvages, Andura, but by those of the place, and the Spaniards the conquerers of that place, Hoga. It is headed and eared almost like a swine; from the chaps hang five long bearded appendices, or the length of som half a foot, like the beard of a Barbel [a type of fish].

It hath flesh verie grateful [pleasing], and good to eat. It bringeth forth live young like as the Whale. As it swim's in waters, it seem's green, yellow, red, and of manie colors, like a Chameleon: it is most frequently conversant about the shore-sides of the lake, and there it feed's upon the leaves of the tree called Hoga, whence also the fish hath its name. It is fearfully toothed and fierce fish, killing and devouring such as it meeteth withal, though they bee bigger then her self: which is the reason why the Fishermen chiefly desire to kill her, as Thevet affirmeth in his Cosmographie."11

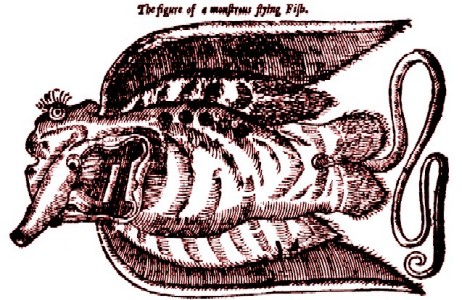

Flying Fish, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgion Ambroise Parey, p. 681 (1649)

"In the Venetian gulf, between Venice and Ravenna, two miles above Quioza, Anno Dom. 1550. there was taken a flying fish, verie horrible and monstrous, beeing four foot long, it had a verie great head, with two eies standing in a line, and not one against another, with two ears, and a double mouth, a snout verie fleshie and green, two wings, five holes in her throat, like those of a Lampreie, a tail an ell long, at the setting on whereof there were two little wings.

This monster was brought alive to Quioza, and presented to the chief of the cittie, as a thing whereof the like had not been formerly seen."12

Although the sketch looks like some sort of horrific Basil Wolverton sketch, this last creature is probably some kind of ray - perhaps a large manta ray.

While there are a few creatures in Paré's menagerie that appear to be fantasic, many of them seem to have features that can actually be found in nature. One can easily see how someone out at sea might mistake the features of a sea animal briefly seen, with the more extraordinary aspects being continually exaggerated with each retelling of the encounter. It helps that Paré is a pretty sober guide who, while he does not dismiss things reported by others out of hand, still manages to remain fairly clinical as one might expect a surgeon to be.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 676; 2 Paré, ibid; 3 Paré, p. 677; 4 Paré, p. 681; 5 Paré, p. 677; 6,7 Paré, p. 678; 8 Paré, p. 679; 9,10 Paré, p. 678; 11,12 Paré, p. 681