Halloween - Pompions and Ghostly Tales: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Pompions, Monsters and Ghosts in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Pumpkins at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy

"Next morning (Oct. 31) we went on shoar at the watering-place, where were come down many country people with Eggs, Hens, Sheep, Goats, Bullocks, milk, Pompions, Fish, Pigeons, citrons, Dates, Oranges, Lemons, and Limes..." (John Covel, Extracts from the Diaries of Dr. John Covel, 1670-1679, Early Voyages and Travels in the Levant, J. Theodore Bent, Ed., Hakluyt Society, London, p. 120)

Pumpkins (or 'pompions' as they were sometimes called during the golden age of piracy) have long been associated with

Halloween, particularly in the form of the carved Jack-o'-lantern.

A turnip carved as a Jack-o'-lantern

Like costumed children running through the countryside demanding treats, the Jack-o'-lantern was not a feature of the holiday at this time in history. Wikipedia does tell us that the term 'jack-o'-lantern referred to will-o'-the-wisps "especially in East Anglia, its earliest known use dating to the 1660s"1. However, its application to carved pumpkins wasn't recorded until 1834, more than 100 years after the golden age.2

Pumpkins originally came to Europe from Central America, with pumpkin seeds reputedly being brought back by Christopher Columbus.3 "One of America’s oldest native crops, pumpkins were an important staple long before Europeans crossed the Atlantic Ocean and discovered them."4

Early 18th century English agriculturist John Worlidge discussed pumpkins in his 1726 dictionary:

POMPIONS or PUMKINS, A Fruit of the nature of Melons and Cucumbers, but much more hardy... When these Plants blossom, let all the dry Shoots be taken away, leaving 2 or 3 main Runners at most; so you'll have them [the pumpkins] grow to a huge bigness; but care must be had that the Heads of those Runners be not hurt. There is a lesser Sort of Pompions call'd Squashes, lately brought into Request; the eatable Root of which boiled and served up with powder'd Beef, is esteemed a good Sauce.5

As Worlidge suggests, some of the things called 'pompions' in the 17th and 18th centuries weren't necessarily the big orange globe we think of today. "They were a crooked neck variety which stored well. Archeologists have determined that variations of squash and pumpkins were cultivated along river and creek banks along with sunflowers and beans."6

Photographer: Rei

The yellow-necked squash posing with it's brethren

Being so plentiful in the New World and being grown on river and creek banks would make pumpkins the perfect food for sailors to grab during landfall. Indeed, pumpkins were mentioned repeatedly in period sailor's journals. Captain Nathaniel Boteler (or Butler) explains that "excellent sea food" includes things like "those various kinds of peas, which are everywhere found in the West Indies (whereof some of them grow upon trees). As also their cascade [footnote 3: Cassava prepared from the tuberous roots of the mandioc.], pompians, potatoes, plantains, oranges, lemons, limes, pines; which are excellent against the scorbute; so that the Dutch men-of-war, which yearly haunt all those coasts, do continually maintain themselves with victual and health with these provisions for many months and years together, until they have made a voyage upon their enemy's coast"7.

Privateer/buccaneer William Dampier mentions pumpkins several times.

[1686] In some places of Mindanao there is plenty of Rice; but in the hilly Land they plant Yams, Potatoes, and Pumpkins; all which thrive very well.8

[1687] The Fruit of the Islands [five islands the seamen named Monmouth, Orange, Bashee, Goat & Grafton] are a few Plantains, Bonanoes, Pine-apples, Pumkins, Sugar-canes &c. and there might be more if the Natives would, for the Ground seems fertile enough.9

So when sailors could get them, pumpkins were a part of their diets, including the buccaneers that sailed with Dampier.

While I haven't come across an account of pirates eating pumpkins, they were known to them. Captain George Roberts mentions them when making the

Artist: Ivan Aivazovsky

Loading Provisions off the Crimean Coast (1876)

case for being let go to the crew of pirate Edward Low.

I told him [Quartermaster John Russel of Edward Low's fleet], I was very sensible that all he said last was true, but hop'd, if they gave me the Sloop, they would also be so generous as to give me Provisions, a small Quantity of which would serve my little Company; but if not, I could go down to the Leeward Islands, where, likewise, I had some small Interest, and I did not doubt that I could have a small Matter of such Provisions as the Islands afforded, namely, Maiz [corn], Pompions, Feshunes [not sure], &c. with which, by God's Assistance, we would endeavour to make shift, 'till it pleased God we could get better.10

It is interesting that Roberts does not consider them the best food, although this is probably not so much a reference their being less preferred than other vegetables, but a nod to the seaman's preference for meat.

1,2 Jack-o'-lantern, wikipedia, gathered 10/24/12; 3 Tim Lambert, A Brief History of Vegetables, Local Histories.org, gathered 10/28/12; 4 Mary Miley Theobald, Some Pumpkins! Halloween and Pumpkins in Colonial America, Colonial Williamsburg website, gathered 10/28/12; 5 John Worlidge & Nathan Bailey, Dictionarium Rusticum, Urbanicum & Botanicum, Vol. 2, 1726, not paginated; 6 History, All About Pumpkins, gathered 10/2/12; 7 Nathaniel Boteler [Butler], Boteler's Dialogues, p. 66; 8 William Dampier, Memoirs of a Buccaneer, Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World -1697-, p. 214; 9 Dampier, p. 288; 10 George Roberts, The four years voyages of Capt. George Roberts, p. 58

Pumpkin Preparation

When we think about eating pumpkins today, the first thing that comes to many people's minds is pumpkin pie.

Artist: Francoise Bonvin

Still Life with Pumpkin and Eggs, (19th century)

However, pumpkins were actually eaten many different ways at this time in history. Native Americans roasted the pumpkins over fires - roasting, baking, parching, boiling and even drying them for later use. They also ate the pumpkins seeds and even added the pumpkin's flower to stews.1

The pilgrims had a particularly strong reliance on them as a food source. In fact, pumpkins were so important to the pilgrims that they are actually mentioned and praised in The Forefather's Song written in the 1630s:

For pottage and puddings and custards and pies

Our pumpkins and parsnips are common supplies,

We have pumpkins at morning and pumpkins at noon,

If it were not for pumpkins we should be undoon.2

One of the pilgrim's recipes was something quite different than the pumpkin pie we tend to associate with them.

The Pilgrims cut the top off of a pumpkin, scooped the seeds out, and filled the cavity with cream, honey, eggs and spices. They placed the top back on and carefully buried it in the hot ashes of a cooking fire. When finished cooking, they lifted this blackened item from the earth with no pastry shell whatsoever. They scooped the contents out along with the cooked flesh of the shell like a custard.3

However, a form of pumpkin pie does appear in cookbooks just before the beginning of the golden age of piracy. The 1656 edition of the cookbook The Compleat Cook contains this recipe:

Artist: Jim Champion, A Pumpkin Pie Slice

To make a Pumpion Pye.

Take about halfe a pound of Pumpion and slice it, a handfull of Tyme, a little Rosemary, Parsley and sweet Marjoram slipped off the stalks, and chop them smal, then take Cinamon, Nutmeg, Pepper, and six Cloves, and beat them; take ten Eggs and beat them; then mix them, and beat them altogether, and put in as much Sugar as you think fit, then fry them like a froiz [froise - what we would call the 'crust' made from the above ingredients - basically this means to fry those things in lard]; after it is fryed, let it stand till it be cold, then fill your Pye, take sliced Apples thinne round wayes, and lay a row of the Froiz, and a layer of Apples with Currans betwixt the layer while your Pye is fitted, and put in a good deal of sweet butter before you close it; when the Pye is baked, take six yolks of Eggs, some white-wine or Verjuyce, & make a Caudle of this, but not too thick; cut up the Lid and put it in, stir them well together whilst the Eggs and Pumpions be not perceived, and so serve it up.4

It's quite a bit different than what we today call pumpkin pie! Closer to the golden age of piracy, Hannah Woolsey's 1670 book The queen-like closet; or Rich cabinet stored with all manner of receipts [recipes] for preserving, candying & cookery features another, much simpler example, a bit closer to what we today recognize as pumpkin pie:

CXXXII. To make a Pumpion-Pie.

Take a Pumpion, pare it, and cut it in thin slices, dip it in beaten Eggs and Herbs shred small, and fry it till it be enough, then lay it into a Pie with Butter, Raisins, Currans, Sugar and Sack, and in the bottom some sharp Apples, when it is baked, butter it and serve it in.5

Jonathan Dickinson gives an account of the use of pumpkins as food during his trek up the eastern coast of the colonies following a shipwreck on the Florida Coast in 1699. Pumpkins first

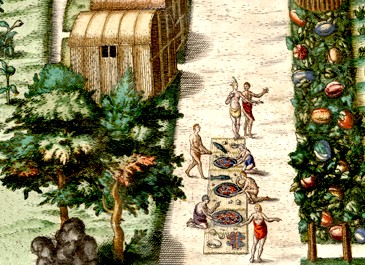

Artist: Theodore de Bry

Native Americans Cultivating Pumpkins, Engraving from A Briefe

and

True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1588)

appear in his account during his journey when he, his family and the ship's crew were traveling with a group of Spaniards they had encountered. They came across

an Indian plantation (this was the first place we saw anything planted) being full of pumpion vines and some small pumpion on them but the Spaniards were too quick for us and got all before us: some of us got a few as big as one's fist. We had a fire there, yet had not patience to dress them as they should be, but put them into the fire, roasted them and eat them. The Spaniards used a great deal of cookery with their pumpions...6

Running out of pumpkins, Dickinson reports that they "borrowed a pot and boiled pumpion leaves, having nothing to put to them but water, which was satisfactory"7. Pumpkins continued to be an important part of the group's diet since it was "the best the place afforded."8 Dickinson seemed to feel that it was a poor diet, "having not much meat"9 leading to several members of their group being "taken with the belly-ache and great scouring [diarrhoea], all which was chiefly occasioned by our unreasonable eating and not governing ourselves therein."10

Of course, when you're dealing with sailors, you eventually learn how foodstuffs can be converted into alcoholic beverages when possible. Mishlaw is an alcoholic beverage usually made using plantains which is described in both

Artist: Cornelis Dusart

Het drinkgelad (!1702)

the accounts by William Dampier11 and Captain Nathaniel Uring. Uring gives the more thorough description of how it is made when he finds himself shipwrecked along the Mosquito Coast (Southern Honduras/Nicaragua).

They take of them [plantains] a certain Number sufficient to make the Quantity of Liquor they design, and squeezing them into small Pieces, put them into a Vessel with as much Water as is proper for fermenting it; and after it has remained in the Vessel two Days, it is fit to drink. The Woman that are appointed to serve the Liquor about, dips the Calabash [a cup made from a gourd] into the Vessel, and takes it out almost full, and with their Hands squeeze the Plantanes and Water together, till it is come to a Pulp, the Liquor running between their Fingers, taking out the Strings, and mixing it well together till it is of such a Thinness fit to drink12

(Believe it or not, Dampier's description is not as good as that.)

More to the point, Uring explains that the man he was living with while shipwrecked "had a great Number of Pumpkins which grew about his House; and his Indian Women used to make Pumpkin Mishlaw almost [every] Day about Four of the Clock in the Afternoon, which served us instead of Tea"13. Uring described the process of making the pumpkin mishlaw, which was fairly similar to the above process except that it was served "when it is hot, we drank it with a good Gust, and passed the Day very cheerfully."14 No doubt!

1,2,3 History, All About Pumpkins, gathered 10/2/12; W.M., The Compleat Cook, 1656, p. 14-5; 5 Hannah Woolsey, The queen-like closet, 1670, p. 256; 6 Jonathan Dickinson, Jonathan Dickinson's Journal or God's Protecting Providence, p. 47; 7 Ibid, p. 48; 8,9,10 Ibid, p. 65; 11 William Dampier, Memoirs of a Buccaneer, Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World -1697-, p. 216; 12 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, p. 152; 13 Uring, p. 153; 14 Uring, p. 145

Pumpkins in Medicine

Although I have yet to find a direct golden age of piracy-era reference to using pumpkins for medicinal purposes, there are a couple surgical references worth mentioning here, .

Photographer: Sengai Podhuvan

Pumpkins with sliced pumpkin flesh

Pumpkin seeds are recommended as part of a prescription given by one of the 'ancients.' (The ancients were the surgeons whose writings still informed most of the medical theory practiced during the golden age of piracy.) Twelfth-century surgeon Albucasis recommended that before cupping the surgeon should anoint the skin with "opening and emollient and resolving oils; if it be in the summer season, with, for example, oil of yellow gillyflower or of violets or of sweet almonds or of pumpkin-seeds."1 Cupping is the process of using glasses open on one end to create a vacuum on the skin. Cupping was thought to draw impure bodily 'humors' to the surface of the skin.

In his herbal guide, Nicholas Culpeper describes pumpkins humoral properties as being cold in the second degree2 and, taken as food, useful for problems with the stomach.3

This is echoed by buccaneer surgeon John Wafer who advises the use of pumpkin-like gourds in his account of traveling across the Isthmus of Darien (modern day Panama).

There are Gourds [here] also which grow creeping along the Ground, or climbing up Trees in great quantities, like Pompions or Vines. Of these also there are two Sorts, a Sweet and a Bitter: The Sweet eatable, but not desirable: the Bitter [is] medicinal in the Passio Iliaca [intestinal blockage], Tertian's [fevers], Costive-ness [constipation] &c. taken in a Clyster [enema]."4

Surgeon Raphael Mission's Clyster Syringe

While he doesn't detail what medicine be used, sea surgeon Thomas Aubrey agrees with Wafer that when treating Iliac Passion, it is "very convenient to begin with Phlebotomy [bloodletting]; after which Clysters will be of great Benefit, in order to evacuate the torrified Excrements, and viscid unnatural Jelly reposed in the Folds of the Intestines, remove the Inflammation of their Tunicles, and take off their depraved convulsive Motion."5 So while they didn't have a large role in medicines like eggs, pumpkins and similar gourds could have some uses to surgeons.

1 M.S. Spink and G.L. Lewis, Albucasis On Surgery and Instruments; A Definitive Edition of the Arabic Text with English Translation and Commentary, p. 664; 2 Nicholas Culpeper, Culpeper's English Physician and Compleat Herbal (1789 Edition), p. 39; 3 Culpeper, p. 40; 4 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, p. 103; 5 Thomas Aubrey, The Sea-Surgeon or the Guinea Man’s Vadé Mecum, p. 92-3