Venereal Disease Treatment Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Next>>

Venereal Diseases in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

VD Medicines: Sudorifics

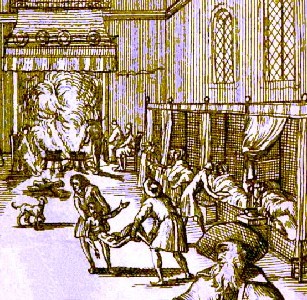

Sudorifics are medicines that cause sweating; the idea was they would help purge the body of the venereal taint via the sweat glands. They were primarily used to treat the syphilis 'stage' of a venereal disease during the golden age of piracy, so sea physician William Cockburn has little to say about them because his book

A Sweating Room, From De Spaanse pok-meeste,

By

David

Abercromby (1691)

focuses on gonorrhea. Sea surgeon John Atkins prefers using mercury-based medicines in treating the pox, so his books are likewise bereft of mentions of sudorific medicines in the treatment of venereal diseases.

Modern historian Claude Quétel explains that guaiac, a brown resin obtained from guaiacum tree, became popular in 1519 when pox sufferer Ulrich Van Hutton published a book extolling its virtues as a cure. Quétel says, "the immediate vogue for g[u]aiac, whose laxative and sudorific properties must be acknowledged, is explained by the gathering reaction against the abuse of mercury."1 This is echoed by sea surgeon John Moyle, who recommends that when sweating a poxed patient, they be given a "spoonful of Spir. Guiac. [to] make him sweat powerfully, for by this way of purging and sweating we usually Cure the Pox at Sea."2

Moyle didn't state that guaiac was the cure-all Hutton suggested it was, however. He instead advised it be used conjointly with mercury, a medicine whose primary benefit golden age doctors felt was the encouragement of salivation. Moyle said that although "the Salivating [caused by mercury], nor sweating [caused by guaiac] courses seldom cures either of them by it self, but both of the courses (bene ordinate) as seldom fails in curing" syphilis.3 Moyle explained that the venereal taint was difficult to remove from the body and "which way soever the malign matter is expelled yet the Reliques of it that remain, are ever further spent by sweat, sweetning of the Blood through the Cuticulares [the epidermis of the skin]"4.

Artist: Forest and Kim Starr - Guiacum Bark

Quétel provides a detailed, modern description of how guaiac was used in treating syphilis during the golden age of piracy.

Wood of the g[u]aiac, a tree imported from Hispaniola, is reduced to a powder, infused [soaked, probably in water], and a decoction is made; this is then simmered. The patient is put in a warm room with a close atmosphere. His intake of food is gradually reduced until he is on a strict diet, and mild purgatives are administered to him. Each day he is required to drink a large dose of decoction of g[u]aiac, after he has made himself begin to sweat by wrapping himself in blankets. After thirty days of what is undoubtedly a debilitating regimen 'the illness has been rooted out'.5

English physician John Sintelaer gave extensive directions on picking the right type of wood to be used to make a decoction of the wood for treating the pox. He advised his reader to "take care to choose that which is not very brown (for the brownest is, the oldest) but rather such as inclining to yellow,

Artist: Jan van der Straet

Preparing Guiacum to Treat Syphilis (late 16th c.)

and of a pretty strong and agreeable Scent, somewhat bitterish and biting upon the Tongue, and so is also the Gum, but of a somewhat browner Colour and tough"6. He also explained how the gum could be extracted from the wood, which could be performed

by laying it before a very hot Fire, when it will drop out by Degrees; you may also draw it out of the Bark, by infusing the Shavings of it in Spirit of Wine, by which means the resinous Párt being Extracted and Incorporated with the Spirit, and the same Being Distill'd from it, the Guumous Particles remain in the bottom of the Vessel, and being afterward precipitated with Water, are dry’d up, and produce a Gum, not inferiour to that which comes from the Tree it self.7

Sintalear points out that wood, bark and gum obtained from the tree were all useful in treating the pox. He noted that "that the young fresh Twigs may prove more efficacious than the dry’d Wood of Old Trees, which is transported into Europe, for, tho' the said Wood, may retain its unctuous and gummeous Part, it must of Necessity lose part of its volatile Salt"8.

While guaiac is probably the most popular sudorific remedy, it wasn't the only one suggested by authors from this period. Quétel explains that it was "progressively replaced by several other woods and roots with sudorific properties" beginning in 1529 when Paracelsus wrote a treatise on syphilis where he "denied that guaiac had any beneficial effect at all."9 Combined with the stranglehold some of the European sellers had on the market for guaiac, these other, similar woods with reputed sudorific properties began to be imported into Europe. They would have been prepared in the same manner previously described.

Sea surgeon John Woodall lists a couple of sudorific woods in his sea surgeon's manual. While he recommends

Artist: Franz Eugen Köhler

Sarsaparilla - Smilax aristolochifolia, From Köhler's Medizinal-Pflanzen (1897)them for their ability to provoke perspiration, most of them had additional properties. Of guaiac (as well as guaiac bark) Woodall says it "doth exiccate [dry], attenuate [reduce the force of], open, purge, move sweate, resisteth contagion, and infection, and doth wonderfully cure the morbius Gallicus [French pox]"10. Other woods which Woodall mentions include sarsaparilla, which is "of a hot quality, causeth sweat, especially extinguisheth the heat of venereous poyson", sassafras, which "is of a hot and drie temperament in the second degree ...[used in] the Morbus Gallicus, or French pox it is a good medicine"11 and China root, which does "prevaile much in the cure of Lues verenea [syphilis]"12. Moyle mentions guaiac several times in his explanations of how to cure the pox, several times combining with similar woods ('Cort. ejusdem')13, sarsaparilla and China root.14

Sintelaer comments on the best way to harvest and use sassafras. He explains that it can also be used,

Photo: Derek Ramsey

Sassafras Tree Bark (Sassafras Albidum Tree)

especially its Bark being of a very strong aromatick Scent, and full of oleagenous Particles. Its Decoction as well as its Oil, is accounted by some a more powerful Remedy against the foul Disease than the Guajacum it self... In choosing your Wood, you must be careful to take that which is of a yellowish Colour, which is more odoriferous and better, than that which inclines to an Ash Colour; the Bark, is still more odoriferous than the Wood, and if Good, ought to be biting upon your Tongue like the Cinnamon.15

Sintelaer also recommends adding other ingredients which he explains can temper the 'hot and dry' humoral quantities of such woods. These include sarsaparilla and China root. Although Woodall advised mixing the roots together, he did not make differentiate them in the same way Sintelaer does.

Of China roots, Sintelaer says "to allay the excessive Heat of the Woods [guaiacum and sassafras] as [well as] to fortify the Sudorifick Vertue [ability to cause sweat] of the Decoction"16. He explains that while China roots are grown in the West Indies, those from the East Indies are 'much better'. "Those that are of a blackish Colour and resinous, are the best, for if they feel light and are pale, you may conclude they are very old, and have lost much of their Vertues."17 Of sarsaparilla, he says the roots are "long and thinnish, and white within; it is accounted to abound more in volatil Particles than the China Root, as may be perceiv’d by its Taste, you must choose those that are not too thin, for the thicker and fresher they are, the better they will answer your Expectation."18

Simple woods were not the only sudorific medicines used. Moyle specifically mentions an 'excellent' and 'powerful' compound sudorific in one of his case studies, which is 'to be taken at intervals.'

Photo: Martin Walker - Antimony Trioxide

Rx. Mercury. Diaphoretic. Bezir. Miner. Corn. Cerv. Ust. (Burnt Hartshorn) Gum Guaic. ana. {of each, 10 grains} Theriac. andromic. (Venice Treacle) {1 dram} Confect[io]. Alekerm[es]. {1 scruple} Syr. Cariphil. [syrup of clove gillyflowers] q.s.s. Bol. [a sufficient quantity to make a bolus]19

The sudorific element in this compound medicine is the bizarrely-named 'Mercury. Diaphoretic. Bezir. Miner.' This preparation, also called bezoarticum mercurial, butter of mercury and several other, similar names, uses mercury in its preparation according to some authors.20 It is referred to in the sea surgeon's dispensatory as Bezoardicum Mineral; being today called Antimony Trioxide. Mercury can be used in its preparation, although the final chemical reaction produces a compound which contains no actual mercury. Bates Pharmacopœia explains that it "is a famous Sudorifick in the Lues Venerea, and ought to be given at Night going to bed in some Sudorifick Vehicle, the Patient being immediately after it well covered, in order to sweat upon it."21

1 Claude Quétel, History of Syphilis, 1990, p. 31; 2 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 93; 3,4 John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 106; 5 Quétel, p. 63 & Hugh D. Crone, Paracelsus: The Man who Defied Medicine, 2004, p. 115; 5,6 John Sintelaer, The Scourge of Venus and Mercury, 1709, p. 233; 8 Sintelaer, p. 237; 9 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 98; 10 Woodall, p. 97-8; 11 Woodall, p. 98; 12 Woodall, p. 97; 13 Moyle, Memoirs, p. 89; 14 See Moyle, Memoirs, p. 89 & Chirugius Marinus: Or, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 152; 15 Sintelaer, p. 236; 16,17,18 Sintelaer, p. 237; 19 Moyle, Memoirs, p. 90; 20 For examples see George Bates, Pharmacopœia Bateana, Translated by William Salmon, 1713, p. 343-4, American Pharmaceutical Association, Proceedings of the American Pharmaceutical Association at the United States, Vol. 46, p. 395; 21 Bates, p. 344

VD Medicines: Mercury-Based Medicines

Mercury or Quicksilver

Judging by the amount written about them, the most popular class of medicines used in treating venereal diseases during the golden age of piracy were those containing mercury. Modern historian Claude Quétel explains that while there were "a mixture of medications at the beginning of the eighteenth century, there was virtual unanimity in favour of mercury, which was considered to be the only specific remedy for the pox."1 However, mercury wasn't restricted to treatment of syphilis; it was also recommended by some medical professionals for use in treating gonorrhoea. Because mercury's identity as a medicine is so closely tied to venereal diseases in history, it seems fitting to explore its history, theory of operation, various compounds and how they were used as well as complications resulting from that use in some detail.

1 Claude Quétel, History of Syphilis, 1990, p. 84

History of Mercury Use in VD

Like venereal diseases themselves, mercury really became important when syphilis 'appeared' in the

Photo: John Hayman

Yaws Lesions on a Man's Leg

late 15th century. Before this, the metal had been employed to treat two diseases which displayed symptoms similar to late-stage syphilis: yaws and leprosy.1

Leprosy is caused by the slow-growing bacteria Mycobacterium leprae. Although it was long thought to be spread through skin contact, the CDC advises that "Prolonged, close contact with someone with untreated leprosy over many months is needed to catch the disease."2 Some of the symptoms are similar to late stage syphilis including the appearance of ulcers (particularly on the feet), loss of vision and disfigurement of the nose.

Although not venereal in nature, yaws is actually caused by a subspecies of Treponema pallidum, the spirochete which causes venereal syphilis. It is a chronic infection spread by direct skin contact which produces lesions in the skin, bone and cartilage and nose disfigurement similar to late-stage syphilis.3

The similarity between leprosy and yaws was seized upon by quacks who extolled mercury as a cure to the venereal outbreak which began to usurp Europe after the French invasion of Naples. Quétel explains,

The accounts of [Josephus] Grunpeck [1496] and [Ulrich von] Hutten [1519] clearly show that almost as soon as the pox appeared charlatans quickly acquired influence over its victims, filling the gap left by the bewildered doctors. In the face of this new and terrifying disease they had one major advantage over the doctors: their audacity. Indeed there was often very little which they were not willing to try4

Practices implemented by quacks were not usually implemented by the professional medical men of the period (at least not publicly), but in this particular case, mercury was soon widely adopted and continued to be popular as a remedy for venereal diseases for centuries afterwards.

1 Deborah Hayden, Pox, 2003, p. 45 & Claude Quétel, History of Syphilis, 1990, p. 31; 2 "How do people get Hansen’s disease?", Hansen's Disease (Leprosy), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website, gathered 4/11/18; 3 "Yaws: A forgotten disease", World Health Organization website, gathered 4/11/18; 4 Quétel, p. 86

Theory of Mercury Use in VD

Like so many of the period medicines, the use of mercury was believed to push undesirable, tainted humors out of the body,

Cover Page to John Atkins' Book

primarily through salivation. Sea surgeon John Atkins explained, "Mercury ordinarily Operates by a Flux [outflow] thro' the Salival Glands"1. He elsewhere notes that mercury "will remove the most confirmed Pox, (or no other Medicine known in the World will;) and this, by returning the contaminated Fluids to a sweet and balsamick Liquor."2

Atkins credit's mercury's tenacity more than any other property the medicine had. As long as the patient continued to salivate, their blood was able to "separate its noxious and incongruous Parts, which are daily washed and spewed out by the thin Liquors continually taken [by 'taken', he means collected by the doctors], and consequently the Remainder, after such a Defaecation, becomes more Homogeneous."3 By this, Atkins means that the excess saliva is produced by the action of the blood removing the tainted venereal humors from itself and pushing them out of the body through salivation. This concept had deep historical roots. Writing in 1527, French physician Jacques de Béthencourt noted that mercury "exercises a vigorous and swift healing action by separating the humours, disposing them to fluxion and then evacuating them."4

Atkins believed that mercury was the only medicine able to "to conquer and carry off the Malignancy... and effectually to subdue the Poison of this Distemper"5. He explains, "The Reason why it has a Power beyond other Medicines for this purpose, is its Gravity, and because constituent Parts are extreme small, smooth and sphærical: The latter Qualification fits them for an admittance into the smallest Passages (even those almost indiscernible ones of the Glands) and its weight breaks all Coagulations, and fits the Morbifick Matter for natural Secretions."6 This is the iatromechanical or physical explanation for the way mercury worked, a framework which would have appealed to practical, hands-on men like surgeons. Claude Quétel explains that iatromechanists

Photo: Wiki User Unkky - Mercury Globules

believed that quicksilver injected into the circulatory system in very small globules travelled through it faster than the blood itself, because of its density; because of its great power of penetration it would pass through blocked capillaries, separate the blood corpuscles and grind up and atomize the particles of the virus which it encountered on its course, expelling them via the saliva.6

This matches Atkins' explanation. He thought so much of mercury in treating venereal diseases that when discussing how to the treat the gonorrhoea 'stage' of venereal diseases, he declared "I am surprized, that every body, by their Practice, should allow Mercury to be only the Foundation and Retreat for Cure, in the last and stubbornest Stage of this Distemper, a Pox, and yet deny its Vertues in a milder Season."7 After all, if it could cleanse the blood of the venereal taint in the later stages, why not use mercury before the venereal poison got a firm hold on the patient?

1 John Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 37; 2 Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 232; 3 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 38; 4 Jacques de Béthencourt, Nova penitentialis Quadragesima, nee non purgatorium in morbum Gallicum, sive Venereum, cited in Claude Quétel, History of Syphilis, 1990, p. 60 5,6 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 17; 6 Quétel, p. 84; 3 Atkins, p. 37; 7 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 18

Mercury-Based Medicines and Their Use

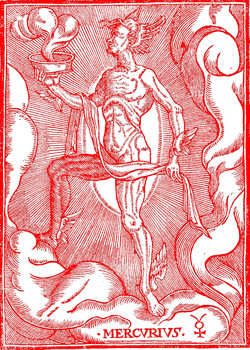

For many people today, mercury brings to mind the shiny silver liquid metal that used to be found in glass thermometers. However mercury took a variety of medicinal forms during the golden age of piracy. Doctors felt that different cases and patients required different types of mercury. Sea

The God Mercury, From the surgions mate,

by John Woodall (1639)

surgeon John Atkins explained, "The Ingenuity of making Mercury Specifical, will lie in the Measure and Manner of Administration; that it suit such Degrees of Infection, and such Constitutions; a Point wherein one Man will excel another, according to their different Capacities, and Opportunities of Experiment"1. Atkins refers both to different types of mercury-based medicines as well as to different ways of administering the medicine.

The primary reason mercury-based medicines were given to treat venereal disease was to cause the patient to salivate. This was considered one of the two most important ways a 'confirmed pox', that is, syphilis, could be purged from the patient's body. (The other was the previous described process of diaphoresis using guaiac and similar woods.) Mercury was multi-talented, however; it also produced diaphorises, diuresis (urine), purging of the alimentary canal and even cauterization of unwanted skin. Because of this, surgeons sometimes used mercury for purposes other than (or in addition to) salivation. However, its primary function with regard to venereal disease was to cause salivation. To start this, the mercury had to be introduced into the patient's body. This was accomplished in four different ways: through the mouth (orally), through the skin (topically), through inhalation and via injection.

Before proceeding to look at the various types of mercury-based medicines, it is worth looking at naval physician William Cockburn's comments. He doesn't discuss mercury in the same detail which he discussed many of the other medicinal classes, but he does mention it. He has a divided opinion of mercury for internal use, as expected. On the one hand he says that mercury and its preparations "have been thought an Antidote to Venereal Poyson; most Authors have thought every attempt, without some of them, to be vain and of no effect." However, he also explains that "Mercurial Medicines are very frequently mix’d in with Cassia; both on the Account of its being a soft and easy Purgative; and also, that it is thought particularly Useful to the Bladder, and Urethra."2 As with the other medicinal classes, he then lists several potential choices of mercury-based purges.

A popular mercurial used in treating venereal diseases was mercury sublimate, a white powder that was also called white sublimate at the time and which is today called

Photo: Wiki User Leiem - Mercury Sublimate

mercury II chloride. Of this medicine, sea surgeon John Woodall says it "is excellent against the Morbus Gallicus [French pox or syphilis], this medicine truly prepared, is a Laxative, a Diaphoretice [diaphoretic - causes perspiration], and Diauretitice [diuretic], a vomitive [purgative], and the best and worst corasive medicine that can be devised."3

Woodall explains that mercury sublimate is the key ingredient in Aqua Falopy, a water given orally to cause salivation. It is named after its inventor, Italian physician Gabriele Falloppio, who described it in his mid 16th century book De Morbo Gallico. Woodall recommends caution in its use, warning his readers that they should "well understand himselfe both in the composition, and administration of any such medicines, or let him cause advise, or rather forbeare them, and use other safer medicines, though their vertues or vices perhaps be fewer."4

Mercury sublimate was also used topically; Woodall himself used mercury sublimate to dissolve unwanted skin from ulcers. It is with such a use in mind that fellow sea surgeon John Atkins recommends the topical use of mercury sublimate in treating skin lesions on the foreskin of the penis which he calls 'shankers' (chancres).5 Naval physician William Cockburn likewise uses it to deal with gummas, soft growths that occur in the last stages of syphilis.6

Another class of mercury-based medicines suggested for use in venereal

Mercuric Nitrate Crystals

diseases by Woodall were mercury precipitates. He explains that these are "Quick-silver distilled in Aqua fortis [nitric acid], which ...is coloured red, or glistering [sparkling], or yellowish... the vapors proceeding from this kind of preparation are also dangerous"7. The reaction Woodall mentions between nitric acid and mercury is toxic, producing brownish-red nitrogen dioxide fumes and leaving behind mercuric nitrate crystals. (A video of this reaction can be seen here.) Woodall says some physicians give it orally by the dram, but "more often [they give it] pill-wise"8.

Woodall mentions that other doctors prefer not to use such a concentrated form of mercury, instead combining it with "Turbith minerall, attributing thereto the perfect cure of the Pox, perswading themselves none can doe like wonders to themselves"9. Turbith is a purging medicine, the idea apparently being that the mercury will eliminate the pox in the blood while the turbith purges the mercury out of the patient's body.

Cockburn mentions mercury precipitate as an internal purge. As with mercury sublimate, he also suggests using it topically for use on gummas.10 Atkins recommends a different form of it - mercury precipitate ruber - as a topical potential cautery to treat skin lesions.11 Atkins' red mercury precipitate is a less caustic form of regular mercury precipitate, being made with a weaker type of nitric acid.

Not everyone was a fan of mercury. About mercury precipitates, English physician John Sintelaer said that mercury precipitate, "by reason of its violent purging and vomiting Quality, which either frequently produce most dangerous Symptoms, or at the best instead of removing the Distemper, transfer it too often only, into another Place... However the white Precipitate is somewhat less violent than the Red."12

Another oral mercurial sometimes used to treat venereal diseases was mercury sublimate dulcis, which is today called mercurous chloride. Apothecary John Quincy explains that it is made by grinding

Sublimation, From The Works of Geber (Jābir ibn Ḥayyān), 1678

mercury sublimate together with crude mercury in a mortar, then heating it in a sand furnace to produce a white powder which appears as a sublimate at the top of the heated vessel. (A brief discussion of furnaces used in making medicines can be found here.) This powder is collected and reheated several times to remove the 'poison' from the mercury. The resulting 'sweet' mercury sublimate was considered less toxic than mercury sublimate; Quincy even suggests its use in treating children with digestive worms.13

Sintelaer recognizes that mercury dulcis is often referred to as "the mildest of all" noting that some physicians said it was "not only a gentle but also a most safe Purge"14. However, he goes on to say that this is not always the case, presenting an example where a patient "who by the Use of it was thrown into a Sali

vation and Frenzy, and died within four

Days after he had taken it"15.

This medicine was given orally; sea surgeon John Moyle uses it in combination with to pilulae rudii and jalap root (both purges) to make a pill to treat gonorrhea16 and in another pill with jalap resin and scammony (also purges) to treat syphilis17. Atkins similarly gives it after an initial dose of mercury vivum (liquid mercury) when treating syphilis18 as well as with conserve of roses to treat gonorrhea.19

Atkins also mentions giving a mercurial bolus to a patient in several cases without specifying what type of mercury he is employing.20 However, in one of his prescriptions, he advises making a bolus using mercury sublimate dulcis as the key mercurial ingredient21, suggesting that it is the likely candidate.

Calomel Powder - Mercury I Chloride

A highly refined version of mercury sublimate dulcis was also used. Sea surgeon Quincy mentions that when the reheating of mercury sublimate is "further repeated to the sixth time, it is call'd Calomel."22 Calomel, or mercury I chloride, was also given orally. In one of his treatment histories, John Atkins gives his patient turbith as a purge to prepare him for salivation, then "followed it three Nights more with Calomel {20 grains} in a Bolus."23 Stephen Blankaart explains in his medical dictionary that a bolus is "a Medicine taken inwardly, of a Consistance something thicker than Hony...as much as may be conveniently taken at a Mouthful."24 So a bolus was a syrupy concoction, probably flavored with some sort of sweetening agent to disguise the taste of the mercury. Cockburn sometimes uses the gentler Calomel for use in his purges in place of mercury precipitate.25

Topical versions of mercury have been mentioned previously as potential cauteries, but topical mercury had another use. An ointment made from mercury was often made and applied to the skin where it would be absorbed in to cause salivation when treating venereal diseases. All three of the sea surgeons under study mention such a medicine. Sea surgeon John Woodall called it Unguentum de Mercurio with

Administering Mercury Paste to a Patient's Groin,

From De recta

curandorum vulnerum ratione,

by Franciso de Arce

(1678)

his recipe containing "Unguent of Dialthea, oleum Laurini [Oil of Bays]. {of each 1/2 pound}. Mercurius vivus. Or quicke silver {2 ounces} oleum spice [Oil of Spike] or Tereb. [Turpentine]."26 John Moyle gives a similarly complex prescription: "Rx. Argent. Viv. [liquid mercury] in Tereb. [turpentine] extinct. {4 ounces} Axung. Porc. [pork lard] {8 drams}. Ungt. Nervin. [nerve ointment] {6 ounces} Misce. exquisite. [mix well] f. Unguent. [make into an unguent]"27. Sea surgeon Atkins gives a much simpler prescription for mercury paste: "Rx. Argent. Vivum [liquid mercury] {4 ounces} Axung. Porcin. [pork lard] {12 ounces} M. [mixed]."28

Woodall does not specifically discuss the mercury paste in conjunction with venereal diseases, instead recommending it to kill lice, treat hemorrhoids and to provoke a 'flux', which was a term sometimes used to refer to salivation. However, both Atkins and Moyle use it for treating syphilis. In a case study, sea surgeon Atkins recommends applying an ounce daily for three or four days, rubbing it into the skin near the wrists and ankles. "This way by Unction I prefer, especially in weak Bodies, the other [way - giving it orally] more certainly causing Nausea, Vomiting, Loosness, Faintness, and the like Accidents that interrupt a Regular Course of Proceeding, and give great uneasiness to a Patient"29. Moyle is a little more generous in his application of the mercury paste, recommending the surgeon begin "at the Soles of the Feet, and so up the Legs, Thighs and Hips, also the Spina Dorsi, Shoulders, Arms and Hands, but not Head, Breast nor Belly"30.

Two methods for administering mercury are mentioned, although they were much less popular than the oral and topical methods. In fact, sea surgeon John Moyle only tells his readers, "You have two wayes to raise the Salivation: Either you do it by Unction [topically], or else by inward Medicine"31, never mentioning either injection or inhalation. However, they are both briefly mentioned by sea surgeon John Woodall and John Atkins explains inhalation in some detail.

Mercury could be injected using a syringe.

Photo: Mission

A Urethral Syringe at a Special Display in the Smithsonian Museum

(Based on the size, it was

more likely used to treat kidney stones than the pox.)

The team excavating Blackbeard's ship Queen Anne's Revenge reported finding "a urethral syringe — a device with a small angled nozzle used to inject mercury into the male urethra to treat syphilis."32 The team's website says that "Analysis of the residue recovered from the interior of the syringe does in fact show a low concentration of mercury."33 (The QAR syringe can be seen on their website here.) However, mercury does not seem to have been typically injected into the urethra, even when treating venereal diseases.

However, the only mention by a sea surgeon of injecting mercury into the urethra from the sea surgeon's manuals comes from Woodall's book. He explains that mercury might be used when injecting vulneraries (healing medicines) into the urethra, although he strongly advises against it. Woodall explains that the vulneraries can be given "with the addition of a little well dissified [probably meaning diluted] mercurie which occasion is, but that warily, namely, seldome or never within the passage, but twixt glans [head of the penis] and preputium [foreskin] daily, if you will upon just occasion"34. The injection of mercury between the glans and foreskin is not done to raise a salivation. In one of his books, sea surgeon Atkins explains that a compound medicine containing plantane water, lozenge of Rhasis and 6 grains of liquid mercury can "be thrown between the Glans and the Fore-skin with a Syringe, and retained there a little to wash and cleanse it"35. Atkins is describing the treatment of a phimosis - a condition where the foreskin cannot be pulled back from the head of the penis. Phimosis was thought to be a complication of venereal diseases at this time, being linked into the Universal Source Theory. However, Atkins never suggests mercury be injected into the urethra.

Photo: Wiki User Leiem - Mercury Sublimate

The other unusual way to administer mercury was via inhalation. This was done using a naturally occurring ore called cinnabar, which is today called mercury II sulfide. Cinnabar was also one of the original sources of pure mercury. It could be crushed and heated in a rotary furnace to extract the liquid metal. Woodall explains that cinnabar "is used in fumes for the pox, is a deadly medicine made halfe of brimstone by Art of fire"36.

John Atkins similarly describes suffumigation (treating a patient with fumes or vapors) suggesting it can be used in place of oral medicines. He explains that "[t]he Fume is made always of Cinnabar".37 He suggests two different cinnabar-based powders in his book for this purpose - one whose primary ingredient was cinnabar and the other whose primary ingredient is artificial cinnabar. To these, Atkins added various healing and binding medicines including styrax, frankincense, turpentine and benzoin.

Opposite to crushing native cinnabar to obtain pure mercury, artificial cinnabar was created by

Mercury Fumigation, From Die Belagert u Entfente Venus, By Blankaart (1689)

combining pure mercury with sulfur and burning them to produce the powder to be used during inhalation. Physician James Quincy declared it to be "the highest Purification of Mercury; as that which is receiv'd from it in the last Operation is preferable to any other for many Purposes."38

Historian Claude Quétel explains the process of mercury fumigation: "At his [the patient's] feet is a portable stove full of embers on which pinches of cinnabar (mercuric sulphide) are thrown from time to time. The patient's body is exposed to fumigation for a long spell."39 Atkins also describes this procedure, although since his description is not quite as clear as Quétel's, it is not used here.

As with the other two medicines he highlights, Woodall warns against the indiscriminate use of cinnabar. He explains that "every horse-leech and bawd [referring to quacks] now upon each trifle will procure a Mercuriall fluxe, yea many a pittifull one, wherby divers innocent people are dangerously deluded, yea perpetually defamed and ruinated both of their good names, goods, healths, and lives, and that without remedy."40

Given the difficulty in administering cinnabar in the close quarters of a ship where fumes would be difficult to contain, this method is most unlikely to have been used at sea.

1 William Cockburn, The Symptoms, Nature, Cause and Cure of a Gonorrhoea, 1713, p. 107; 2 John Atkins, Lues Venerea, not dated, p. 19; 3 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 115; 4 Woodall, p. 61; 5 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 34 & John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 238; 6 Cockburn, p. 166; 7,8,9 Woodall, p. 299; 10 Cockburn, p. 166; 11 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 34; 12 John Sintelaer, The Scourge of Venus and Mercury, 1709, p. 169; 13 John Quincy, Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea, 1719, p. 255; 14,15 Sintelaer, p. 167; 16 John Moyle, Chirugius Marinus: Or, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 139; 17 Moyle, p. 144; 18 Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 230; 19 Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 232; 20 See for example Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 27 & Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 232 & 234; 21 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 25; 22 Quincy, p. 255; 23 Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 248; 24 Stephen Blankaart, The Physical Dictionary, 4th ed., 1702, p. 43; 25 Cockburn, p. 107; 26 Woodall, p. 49; 27 John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 86-7; 28 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 38; 29 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 39; 30 Moyle, Memoirs, p. 87; 31 Moyle, Chirugius Marinus, p. 148; 32 Lindsey Bever, "Morning Mix: Even the pirate Blackbeard offered an employee health-care plan", The Washington Post, January 30, 2015, gathered from the web 4/15/18; 33 "Urethral Syringe", QAR Project Website, gathered 4/15/18; 34 Woodall, p. 62; 35 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 34; 36 Woodall, p. 300; 37 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 47; 38 Quincy, p. 258; 39 Claude Quétel, History of Syphilis, 1990, p. 60; 40 Woodall, p. 300

Problems of Mercury Use in VD

"Mercury is a fox, and will be too crafty for fooles, yea an will oft leave them to their disgrace, when they relying upon so uncertaine a medicine, promise health, and shall in stead of healing make their Patient worse than before." (John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 299)

People are acutely aware these days of the danger of mercury poisoning. Because mercury was such an important part of the medical treatment, particularly in the realm of venereal diseases, it is sometimes assumed that the dangers were not well understood in the past. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Historian Claude Quétel points to a variety of late 15th and 16th century

French Physician Jean Fernel

physicians who warned against the immoderate use of mercury as a medicine. As early as 1497, close on the heels of the apparent Neopolitan introduction of syphilis to Europe, physician Alexandri Benedicti discussed "complications resulting from the excessive use of mercury - shaking and paralysis, the loosening and loss of the teeth, and so on."1 By 1548, French physician Jean Fernel had dramatically expanded the list of mercury poisoning symptoms:

the throat becomes ulcerated; the tongue, palate and gums swell; the teeth become loose; saliva runs constantly from the mouth, unimaginably fetid, and so contagious that the lips and the interior of the mouth become ulcerated on contact with it. Because this stench chills and upsets the stomach, the patients lose their appetites and are tormented by an unquenchable thirst; they can scarcely drink, however, because each one's mouth has been transformed into one huge ulcer. Even their speech is unintelligible, and they become deaf, sometimes incurably so. A foul smell pervades the place they inhabit.2

The detrimental effects of mercury were not lost upon the sea physicians and surgeons active around the golden age of piracy. Sea surgeon John Woodall's warnings against the abuse of mercury have already been mentioned several times. John Atkins lamented, "I cannot but think most of those deplorable Objects, found in Hospitals, or elsewhere, whose ruined Constitutions are attributed to the Lues, to be with more Truth and Justice ascribed to Mercury."3 Atkins elsewhere rages, "the Fall of so many Noses is owing to, the Disgrace of a Country and Profession; because in my Opinion, the Distemper alone would scarcely ever do it; and this I ground from my Observations in Travel, that where Mercury is not known or much used, they keep their Noses."4

Just to be clear on what they had right and what they had wrong, let's look at what the CDC lists as the consequences of mercury poisoning. High concentrations can cause rapid, severe lung damage and irritation and corrosion of the digestive system (including the mouth). Longer term exposure can result in neurological disturbances, memory problems, skin rash and kidney abnormalities.5 So while Atkins was confusing the symptoms of syphilis with those of mercury poisoning when it came to the loss of the patient's nose, most of Fernel's symptoms would have been logical outgrowths of the sorts of problems specified by the CDC.

Like so many modern medicines in use today, the period medical men felt the perceived benefits of a medicine had to be balanced with its recognized side effects. John Atkins was particularly vocal in defense of mercury, provided the practitioner was experienced in working with it and understood the patient well enough to "be able to [recognize] when the Mercury operates kindly, and whether the Patient's Constitution and Courage will support him thro' the Course"6. He explained to his readers that he would "repeat the Mercurial Bolus, and purge no oftner than Reason tells me their [the patient's] Strength will admit, without a Hypercatharsis [excessive and frequent defecation], Fainting or Loathings (which is with some every other Day, with others twice a Week, or less)"7.

Atkins felt that while improper use of mercury created problems, proper use allowed the patient to get the most benefit from it. For example, Atkins warns, "Too long a Course of Mercurials will sometimes bring on Running [from the urethra] of uncommon Colour and Quantity, Alopecia [loss of hair], Inflammation, cold Sweats, Fever, &c."8 (Although the CDC doesn't mention it, hair loss and discolored fingernails have been suggested to be additional signs of mercury poisoning.9) However, other problems occurred when "there is too cautious and long an adherence to Mercurials, or irritating Medicines... [then] the Running goes on without end, and at last brings an irrecoverable Laxity on the Parts, converting a Venereal to a troublesom Seminal Gleet."10

Atkins felt such problems could be corrected with other medicines. For example, if the mercury was failing to work properly, "we may safely divert [it] with Catharticks [purging drugs]... [as well as] giving a Respit for a Day or two, a Hartshorn Drink, and an Anodyne [pain relieving] Draught."10

Italian Mercury Pill Container, Wellcome (18th c.)

Hartshorn shavings were believed to resist poison and restore lost strength, among other things, so a hartshorn drink would theoretically divert the poisonous mercury. Atkins elsewhere explains that "Purges are given after Mercurials ...from a distant View of altering the Habit of Body, and carrying off those vicious Humours that would else probably take their Course that Way, and heighten the Fury [of the mercury]."11 He elsewhere says "Purges are designed likewise to prevent any ill Effect from too great a Quantity of Mercury remaining at once in the Body."12 Atkins explains that such observations are based on his own practice.

Atkins even explained when mercury was appropriate and when it was not. In one of his case studies, Atkins observes the effects of mercury in causing salivation in a patient. He notes that "if through any peculiar Dyscrasy [bad mixture of medicine], or ill-timed Administration... it [mercury] never operates kindly towards the Mouth, but either kills, or renders the Distemper more pertinacious [resolute]."13 If this occurs, he warns that a salivation is inappropriate. To help his readers to recognize when he has seen this work, he explains that "A good Prognostick in these Mercurial Courses, is when the Glands of the Mouth are soon wounded, and the Discharge by Ulcers [in the mouth] (if any) are lessened immediately, and drying up"14. However, if the mouth does not form these ulcers, Atkins insists "it is best to strike off early, to give no more Mercury than is within your Power and the Patient’s Strength to purge off again; such must be contented with Palliatives [anodynes or pain-killers] til a better Opportunity."15

1 Alexandri Benedicti, Veronensis physici historiae corporis humani, cited in Claude Quétel, History of Syphilis, 1990, p. 31; 2 Jean Fernel. Joannis Fernelli ... de Abditis rerum causis..., cited in Quétel, p. 62; 3,4 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 231; 5 "Mercury Factsheet", Center for Disease Control, gathered 4/18/19; 6 John Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 42; 7 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 27; 8 Atkins, Navy Surgeon, p. 233; 9 H Wüstner H, C.E. Orfanos et. al., "Nail changes and loss of hair: cardinal signs of mercury poisoning from hair bleaches", Dusch Med. Wochenschr., 1975 Aug 22, gathered from Pubmed, 4/19/18; 9 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 28-9; 10 Atkins, Lues Venerea, p. 42; 11 Atkins, Navy Surgeon, p. 232; 12 Atkins, Navy Surgeon, p. 233; 13,14,15 Atkins, Navy Surgeon, p. 250