The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

The Pirate Surgeon's Quarters in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Pirate Vessels: The Data

In an effort to determine what types of vessels

Artist: Francis Swaine

Foudroyant 80 Gun French Ship Captured by Monmouth, Hampton Court and Swiftsure (1758)

were used by pirates during the golden age of pirates (1690-1725), data from several period sources was used where such vessels were mentioned. Sources included government documents, pirate trials, eyewitness accounts, the rare pirate accounts, newspaper articles and books from the period. Vessels for which the captain or commander were not found or able to be determined were removed from the data. Where a captain or commander was determined but the vessel name could not be found, the name 'Unknown' was assigned to that vessel.

This resulted in a database of 680 vessel/captain or commander combinations. The information gathered for each vessel includes 1) The vessel name, 2) The man who captained it or the commander who was in charge of it if it was in a fleet of pirate vessels and the individual captain's name is not mentioned or cannot be determined from other data, 3) The type of vessel, 4) The burden or tonnage the vessel could hold, 5) The number of guns, referring to cannons, 6) The number of swivel guns, referring to small cannons on a swiveling base which were

Photo: Wikimedia User Brokensphere

Swivel Gun or Paterero On Modern Reproduction Schooner Lynx

usually mounted to the side of a ship (sometimes called patereros in the period data), 7) The number of men on the vessel, 8) The date on which the vessel was seen and 9) The source of information.

This data was sorted by vessel name/captain or commander so that a full picture of these vessels could be assembled. From this, a master entry for each ship/captain or commander combination was created, resulting in 195 individual combinations. Note that some ships were captained by more than one pirate in cases where they changed ships, mutinied against their captain or the pirate captain died and a new one was elected. As an example of multiple captains, the 500 ton ship Cassandra, which was active in the East Indies, was variously attributed in the data to captains Edward England, Jasper Seagar and John (Richard) Taylor1. In an example of election of a new captain upon the death of the old one, Howell Davis, captain of the ship King James died on Principe on the west coast of Africa, and Bartholomew Roberts was elected to command the ship.2 A mutiny against pirate captain Howell Davis occurred because he refused to attack English vessels and Samuel Bellamy was chosen the new captain of the sloop Mary Anne.3 To preserve the integrity of the data, each of these is included as a separate entry, although it inflates the total number of vessels found in the data.

It must be noted that each entry is only as accurate as the observer who recorded it. Many of the numbers these witnesses give describing tonnage, guns and men are improbably round numbers. They are almost certainly guesses based on their interaction with the pirates. The accuracy of the guess would have depended on many factors including the experience of the observer and their ability to accurately

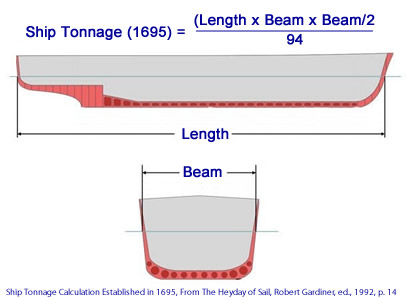

Based on a Graphic by Wikimedia User Emoscopes

Vessel Tonnage Calculation Established in 1695 And In Use Until 1773

guess what they were seeing in the time they were engaged with the pirate under observation. In addition, an account by one witness may provide different data than that of another, even when they occurred fairly close in time to each other. This might be explained by the already mentioned accuracy of the witness or changes that the pirates made to the ship made between encounters such addition or subtraction of men or guns.

Guns were also stored in the hold at times, although most witnesses would have no way of knowing this. In one rare instance, the account of the capture of Louis Guittard's 200 ton ship La Paix mentions that his ship "was armed with twenty iron guns placed on her main deck, and with eight placed in her hold; and she carried thirty-two barrels of powder in her magazine."4 Here, the person reporting had the benefit of seeing the ship after she was captured. Because of such variations in witness accounts, many of the ship master entries show a range of guns, men and, in a few cases, even tonnage. Since a ship's tonnage during this period was based on the formula seen in the graphic at left, it it is likely any witness observation of a pirate vessel's tonnage would have been a guess.

Blackbeard's ship Queen Anne's Revenge is mentioned in the period data sources as being about 200 tons (which is the number used here). However, the ship found by Intersal, Inc. offshore of Beaufort, South Carolina which is believed to be the original vessel is 103 foot long and has a 24.6 foot beam.5 Putting these numbers into the above formula gives us a much different ship tonnage of about 331, although it is not clear that their measurement of beam and length is the same as is shown.

1 See Clement Downing , A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 44 & 48, Ed Fox, "63. Adam Baldridge, Deposition of Adam Baldridge, 5 May, 1699. CO 5/1042, no. 30ii. printed in Jameson Privateering and Piracy, pp. 206-212", Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 209 & The Indian Antiquary, S. Charles Hill, ed., Vol. 49 April 1920, p. 62; 2 The Tryals of Captain John Rackam, and Other Pirates, 1721, p. 30; 3 Joel Baer, British Piracy in the Golden Age, Vol. 2, 2007, p. 289; 4 Philip Alexander Bruce, Institutional History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century, 1910, p. 219; 5 Queen Anne's Revenge, wikipedia, gathered 11/5/12 - note that this is based on modern measurements.

Pirate Vessels: Large Craft

"[Blackbeard's fleet] sailed to Carolina, taking a Brigantine and two Sloops in their Way, where

they lay off the Bar of Charles-Town for five or six Days... [the pirates]

Artist: Benjamin Cole

Blackbeard in Front of His Ships in Battle,

from A General History of the Pyrates

(1724)

struck a great Terror to the whole Province of Carolina, ... [they] being in no Condition to resist their Force. They were eight Sail in the Harbour, ready for the Sea, but none dared to venture out, it being almost impossible to escape their Hands. The inward

bound Vessels were under the same unhappy Dilemma, so that the Trade of this Place was totally interrupted". (Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 74)

Certain benefits accrued to a group of pirates with a large ship as Edward Teach's chapter in Charlestown's history testifies. During his blockade of Charlestown's port in May 1718, where had had "a Ship of 40 Guns, called the Queen Anne’s Revenge, 350 Men, and two Sloops, one of 10 Guns and 90 Men, the other of 8 Guns and 50 Men"1. During Stede Bonnet's trial, the Queen Anne's Revenge was described as being "as well fitted with Warlike Stores of all sorts, as any Fifth-Rate Ship in the Navy"2 With this powerful ship and a couple of faster, lighter sloops to chase down anyone attempting to defy him, Blackbeard was able stop every vessel attempting to to sail past Charleston Bar. This culminated in his taking several prisoners and ransoming them for a badly-needed medicine chest.3 The value of a large ship could be significant to a pirate captain.

We must begin the discussion of large vessels with the definition of a ship since all of the large vessels in this list would have been ships. A 'ship' was at this time defined as "all great Vessels with Sails, fit for navigation on the Sea; excepting Galleys, which go with oars"4. Modern historian David Cordingly refines the definition, explaining that a ship was typically recognized by a sailor of this period as being "a sailing vessel which had three masts with square-rigged sails throughout."5 In fact, the term 'ship-rigged' is the same as Cordingly's definition.

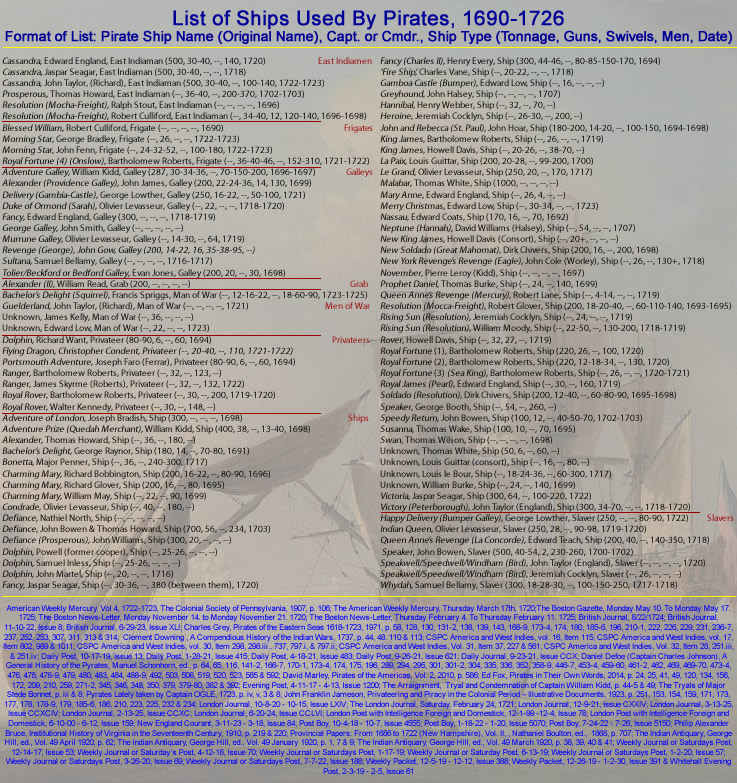

The list of large vessels identified as 'ships' can be found in the data set is shown below.

Large Vessels in Use by Pirates During the Golden Age of Piracy Based on Period Sources |

This list is organized first by ship type (where one is identified other than ship), then alphabetically by ship name and finally by the Captain's or Commanders name in cases where the same ship name appears more than once. A couple of points about the data in the list are worth mentioning. First, when numerical data was not available for the tonnage (burden), number of large guns or cannon, number of swivel guns, number of men or years that the data indicates the vessel was used, the symbol '--' appears in the parenthesis as a placeholder. Second, the dates shown may not necessarily represent the entire life of the vessel as a pirate; this information is based strictly on what is found in sources used to create the list. Finally, although all the vessels on this list are ships, some of them were called by other names which provided more information on their design. These types are listed in red at the far right of each column.

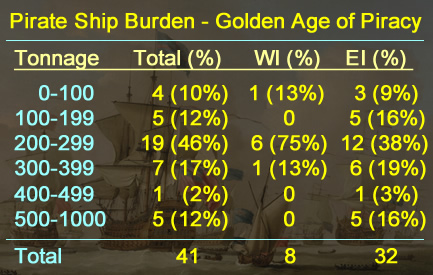

There were a wide range of different ship sizes as measured by the burden (cargo capacity of the

Large Pirate Ships By Type, Background Image of

Woodes Rogers' Duke Taking a Manila Ship (1889)

ship calculated in tons as previously explained). The pirate ships for which tonnage is mentioned in this data can be seen in the chart at left. The first column gives the capacity of a ship broken down by hundreds of calculated tons. The second column gives the total number of ships in each tonnage category for which the tonnage has been found in the data. Because there is a notable difference in the number of pirates on ships found in the West Indies (WI) (which includes the Caribbean and the New England Coast) and East Indies (which refers primarily to the Indian Ocean), the number of ships found in each of these places has been broken out in columns three and four. (See page five for a full discussion of the differences in vessel size difference between these two locations.) Ed Fox points out that the percentages shown in this data would probably be different if the tonnage was known for the other 55 vessels. Significantly, this makes up almost 60% of the ships.

It is immediately obvious from this data that there were a lot more ships available to pirates in the East than the West Indies. Yet, even there, the largest ships were in the minority. There is only a single ship recorded in the East Indies in the 400-499 ton range. That ship is Captain Kidd's captured prize Quedah Merchant, which he refers to as the Adventure Prize. Significantly, he did not use this vessel until his own, smaller 287 ton Adventure Galley was sinking.6 There are couple ships of burdens greater than 500 tons in the East Indies. However, this number is greatly inflated by the fact that the 500 ton Cassandra is listed in three separate ship/captain pairs in the data.7

_Wenceslas_Hollar_17th_c.jpg)

Artist: Wencelas Hollar - Two Dutch East Indamen (17th century)

When this data is collapsed into a single entry, there are really three ships in this category - the Cassandra, John Bowen & Thomas Howard's unnamed 700 ton ship and Thomas White's 1000 ton Malabar. The majority of the East Indies-based pirate ships for which tonnage is mentioned fall into the 100 to 400 ton category, comprising 73% of the data.

In the West Indies, there are no examples in the data of a ship of more than 400 tons. In fact, the only ship to appear in the 300-399 ton category is Samuel Bellamy's slave ship Whydaw, which is rated at the lowest end range at 300 tons. The other seven ships found in the West Indies for which tonnage is known are all less than 250 tons. Curiously, historian Angus Konstam says "the average size of English (from 1707, British) merchant ships coming during the 'golden age' of piracy was between 100 and 200 tons".8 In fact, most of those found in this data are between 200 and 250 tons.

All other things being equal, larger vessels would have been more accommodating to a surgeon than smaller ones because they would have provided him with more space below deck where the operating theater was located. A number of pirate surgeons served on large ships. Robert Hunter was forced aboard George Lowther's 250 ton ship Happy Delivery where he served for about a year.9 Richard Moor was a surgeon's mate aboard the Comrade Galley under Jeremiah Cocklyn.10 Notorious surgeon Peter Scudamore was elected to be the head surgeon in Bartholomew Roberts' fleet of ships, which earned him quarters aboard the fourth Royal Fortune.11 Several unnamed surgeons are mentioned being aboard large pirate ships including Samuel Bellamy's 300 ton Whydah12, John Hoar's 200 ton ship John and Rebecca13 and John Bowen's 100 ton ship Speedy Return14.

1 The London Journal, Saturday, February 24, 1721; 2 The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, 1719, p. 8; 3 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 74; 4 Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, Vol. 2, 1728, p. 68; 5 See Ed Fox, “6. Richard Sievers. Deposition of Richard Sievers, 19 December, 1699. HCA 1/98, ff. 11”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 40-1 & Fox, “63. Adam Baldridge, Deposition of Adam Baldridge, 5 May, 1699. CO 5/1042, no. 30ii. printed in Jameson Privateering and Piracy, pp. 206-212", p. 350; 6 John Franklin Jameson, “76. Narrative of William Kidd. July 7, 1699.”, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period – Illustrative Documents, p. 186; 7 Edward England and Jaspar Seagar: Clement Downing , A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 44, Jaspar Seagar alone: Fox, "44. Richard Moor, from The Examination of Richard Moor, 31 October, 1724. HCA 1/55, ff. 94-97", p. 171, and John (Richard) Taylor: "John Freeman, deposition March 1723 "India Office Miscellaneous Letters Received, Vol 14, No. 162" & "Letter from Jamaica to Humphrey Morrice, Esq., 12 May 1723", The Indian Antiquary, S. Charles Hill, ed., Vol. 49 April 1920, p. 62. In fairness, there were probably only two captains of the Cassandra, Taylor and Seagar, but the data in Downing is not clear on this point, so to preserve the integrity of the information, it is included under three captains; 8 Angus Konstam, The Pirate Ship 1660 -1730, p. 23; 9 Weekly Packet, 12-5-19 - 12-12, Issue 388 & Eric J. Graham, Seawolves: Pirates & the Scots, 2005, p. 108; 10 Fox, "44. Richard Moor, from The Examination of Richard Moor, 31 October, 1724. HCA 1/55, ff. 94-97", p. 207-8; 11 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 275; 12 Jameson, “112. Trial of Simon van Vorst and Others. [October], 1717.”, p. 260; 13 CSPC America and West Indies, Vol. 16, Item 115 & Jameson, "65. Deposition of Samuel Perkins. August 25, 1698", p. 160; 14 Charles Grey, Pirates of the Eastern Seas 1618-1723, 1971, p. 237 & Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 522

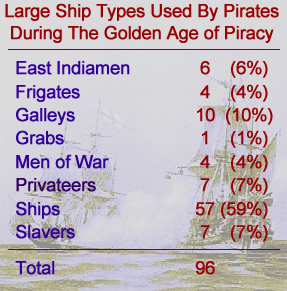

Pirate Vessels: Large Craft Types

Large Pirate Ships By Type, Background Image of

Woodes Rogers' Duke Taking a Man ill a Ship (1889)

The breakdown for the vessel types named is seen in the chart at left. Note that the majority of these large vessels are simply referred to in the data as being 'ships'. This may have been because the observer didn't have the time, knowledge, or familiarity with specific types of ships to give a more accurate name to them, or it may just be that the ship was just a regular three-masted merchant vessel. (Nearly all of the pirate ships were captured vessels, many of which were repurposed merchant vessels.)

Some observers, likely those who were more familiar with different ship types of the time, mentioned the pirates' ships being of more specific types. Among the pirate ships recognized with a more specific function were East Indiamen, Frigates, Galleys, Grabs, Men of War, Privateers and Slavers (also called Guineamen during this time). These names indicate the purpose the ship was either built or used for before the pirate captured her. They are treated in this article as subclasses of the more generic term ship.

Ship types can be classified in several different ways. Period encyclopedist Ephraim Chambers divides ship types into three broad 'classes'

Artist: Abraham Willaerts - A French Galley & Dutch Man of War (17th century)

based on their function: "Ships of War, Merchant Ships, and an intermediate Kind, half War, half Merchant; being such, as tho' built for Merchandise, yet take Commissions for War."1 Chambers chooses to exclude galleys from the definition of ships, suggesting that they were different than ships because they were propelled by oars. Chambers' organization is not the only one proposed for classifying ships. In his book Pirates of the Eastern Seas, Charles Grey suggests that "ships were broadly of two classes, galley built, and frigate built."1 This definition focuses on the structure of the hull of the ship instead of its function. This article begins with a look at Grey's categories of galley and frigate ships and then examine the ship types which fall into the function-oriented classes proposed by Chambers.

Before discussing the individual ship types, it must be mentioned that many ships fit into more than one category. In fact, a several are referred to being different ship types in the period accounts.

Artist: Thomas Luny - Two East India Ships Hove To (1796)

For example, the former East Indiaman Mocha, renamed Resolution by the pirates, was at different times referred to as a privateer2, a frigate3, a ship4 and an East Indiaman5. Appearing in the data under two different ship/captain combinations, it is referred to in this case by its original and most specific type - an East Indiaman.

All of the vessels which have been generically labelled 'ships' by period observers would actually have been better described by Grey's hull type and Chambers' functional type. However, without more information they can only be referred to here generically. In every case where the data provides a more precise term than 'ship' that term is used.

1 Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, Vol. 2, 1728, p. 68; 2 Charles Grey, Pirates of the Eastern Seas 1618-1723, 1971, p. 169; 3 The Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Captain William Kidd, p. 17; 4 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 447 & John Franklin Jameson, “65. Deposition of Samuel Perkins. August 25, 1698.”, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period – Illustrative Documents, p. 159; 5 Jameson, “72. The President and Council of the Leeward Islands to Secretary Vernon. May 18, 1699.”, p. 177