Plague Quarantine Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Maritime Quarantine For Plague, Page 3

Bubonic Plague: Mediterranean

Of the three areas of quarantine under study during this period - the Mediterranean, England and the New World - the Mediterranean has the longest history of dealing with quarantine. As a result, it also had the most advanced and well thought-out response to the problem.

Unfortunately, much of documentation of quarantining of the plague in the Mediterranean is written in old Italian and is difficult and time-consuming to try and translate. Fortunately, there is a large body of research on the topic and there are many, many (many) books and articles on the subject. However, these are not original, GAoP documents usually providing brief quotes related the more detailed aspects of quarantine.

For this article, the 1695 lazaretto regulations of Messina - Instruzzioni e governo del lazzaretto di Messina per la scala franca - are used where possible to illustrate and explain the procedures in use by people running the lazarettos during this period. The other Italian lazarettos tended to imitate the regulations established in Venice, so these regulations are a relatively good proxy for what was used throughout Italy. Since the language in the Messina rules is a bit arcane and the copy is not the best (and the author is in no way fluent in old Italian), the 1728 regulations are also used to help interpret the earlier rules when necessary. In using them, it was noticed that the two sets of regulations are remarkably similar to one other, frequently containing only small changes in wording and minor changes to process details between the two periods. There are often no changes at all between sections of the two documents, other than spelling and syntax.

In addition to the Messina rules, accounts given by various English sailors and visitors to Mediterranean ports are used to illustrate the lazaretto experience. Of particular value because of its detailed explanation of the workings of quarantine is the account written by Scottish physician John Howard. Howard made a study of the Mediterranean lazarettos in 1785 and 1786, explaining, "I went abroad for the purpose of visiting the principal lazarettos in France and Italy. To the Physicians employed in them, I proposed a set of queries respecting the nature and prevention of the plague; but their answers not affording satisfactory instruction, I proceeded to Smyrna and Constantinople."1

Artist: Mather Brown - Surgeon John Howard

(1789)

Howard was so interested in understanding the lazaretto experience that he intentionally boarded a ship with a 'foul' bill of health sailing from Smyrna, Greece in 1786 so that he could serve out a full term of quarantine at Venice. Howard provides very detailed descriptions of the process, providing details not found in the Messina regulations. He explains that much of his account is "copied from the sketch of an information sent to our government in 1770... I carefully examined this sketch during my quarantine of forty-two days, and I have here given it with a few corrections and observations."2 Even the original account is about 45 year late for the period of interest. However, Howard also notes that while he was serving his quarantine, he asked the prior (president) at Venice to see the rules for the lazaretto. The prior "presented me with a printed copy, entitled Commissioni in via d'instruzione, al nuovamente eletto Priore del lazarreto. In Venezia 1726, quarto, 48 pages."3 This would have been contemporary to the 1728 Messina regulations which, as noted, are very similar to those printed in 1695. With that in mind, Howard's extensive descriptions are included where they help fill in missing parts of the process, with the caveat that they were written 60 years after the end of the period of interest.

1 John Howard, An Account of the Principal Lazarettos In Europe, 1789, Vol. 1, p. 18; 2 Howard, p. 12; 3 Howard, p. 12

Bubonic Plague: Mediterranean - History of Regulations

Much of the history of preventing the bubonic plague through quarantine is land-based rather than maritime.

Artist: William Brassey Hole - Outcast Biblical Lepers (c. 1925)

Several authors point to the Bible, particularly Moses' command to Aaron to have a priest determine who had leprosy and then "shut up him that hath the plague, seven dayes. And the Priest shall looke on him the seventh day: and beholde, if the plague in his sight be at a stay, and the plague spread not in the skinne, then the Priest shall shut him up seven dayes more."1 If the person still had signs of leprosy after that, they were declared unclean, were to "dwell alone, without the campe shall his habitation be."2 Further instructions to quarantine lepers can be found in the bible in Numbers and the first book of Samuel. However, the Hebrew "lazarettoes, it appears, were little used in connection with foreign trade, leaving out of the question commerce by sea. ...Had the Jews been active in outside commerce, we should probably read in the Old Testament of sanitary laws applicable to caravans and vessels."3 Still, the Mediterranean plague quarantines worked along lines similar to what will be discussed here, although their quarantine period was longer.

It was not until the fourteenth century were that the maritime quarantine still in use during the golden age of piracy appeared. The fairly standard period of quarantine may have begun when "the Knights Hospitallers of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem first adopted a forty-day quarantine after their establishment on the island of Rhodes in 1306."4 Decades later, following an outbreak of bubonic plague in Ragusa (in what is today Dubrovnik, Croatia), "the city’s chief physician, Jacob of Padua, advised establishing a place outside the city walls for treatment of ill townspeople and outsiders who came to town seeking a cure."5 Ragusa initially imposed a thirty day quarantine, which was later expanded to forty days and, in the winter, fifty days.

Artist: Odoardo Fialetti

Unloading a Vessel, From

Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Venice, (ca. 1606)

"During a plague epidemic in 1377, the town council held both foreigners and locals together with their merchandise when they returned from areas considered pestilential. The month-long detention took place on the nearby island of Makan."6 The island location was likely chosen for its isolation rather than its convenience in stopping incoming ships from making port. However, later buffer island-based lazarettos were used in part because they provided a good place to send arriving ships.

The independent city-state of Venice was the first to establish a digest of rules known as the Laws of Quarantine, designed prevent the plague from reaching the city.7 Venice appointed three guardians of public health in 1348 - Nicolaus Venerio, Marinus Querino, and Paulas Belegno - who were charged with inspecting ship's crews for signs of the plague as well as some other diseases. Suspect crews, goods and ships were sent to serve out their quarantine on an island in the lagoon.8 "By 1374, new ordinances forbade the entrance of suspected ships to the harbor altogether, and required custody of their crews for thirty days (the so-called trentina)."9 By 1383, a forty day quarantine was employed at Marseille, France.10

Following a series of plague epidemics around the turn of the fifteenth century,

Artist: Jan Brueghel I -Port Scene in Venice (c. 1600)

the Venetians took an island belonging of the hermit monks of St. Agostino. Eighteen century Venetian Giovanni Tiepolo wrote, "1403. The pest began at Venice. A place for a lazaretto was seized from Friar Gabriel, of the order of Hermits, and Santo Spirito was given to him."11 Here, "Venice established ...a hostel on the island of Santa Maria not just for the detention of travelers, but also for the internment of local plague suspects. …where they were now subjected to a longer isolation period, the forty days or quarantine."12 So this, like most maritime lazarettos, served both sailors and landsman.

Outside of the individual quarantine stations and lazarettos, Italy created what is probably the pinnacle of systems to prevent communicable diseases from this era. The Italian states established special Magistracies who had legislative, judicial and executive powers in public health matters with their prime focus being the prevention of the plague. "By the middle of the sixteenth century, all major cities of northern Italy had permanent Magistracies, reinforced in times of emergency by health boards set up in minor towns and rural areas. All boards were subordinate to and directly answerable to the central Health Magistracies of their respective capital cities."13

Professor Andrew Cliff explains that the Italian plague system which developed from this root had two parts: communication and defensive isolation. To facilitate communication, northern Italian Health Magisteries kept each other informed about the health conditions in places where the plague was most likely to strike

Artist: Giovanni Giacomo di Rossi

'Guarding a River with Ropes to Prevent Boats From Entering Without Notice', From A

Series of

Engravings - 'The Plague in Rome' (1656)

during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries including Italy, Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. "For example, Florence 'corresponded' regularly with Genoa, Venice, Verona, Milan, Mantua, Parma, Modena, Ferrara, Bologna, Ancona, and Lucca. The frequency of the correspondence with each of these places ranged from one letter every two weeks in periods of calm to several letters a week in times of emergency."14

Defensive isolation is where maritime quarantine came to the fore. When the plague or similar communicable disease occurred somewhere, a long-term ban was imposed on trade with that location by the Italian ports without active maritime lazarettos. When communicable diseases were only suspected, a temporary suspension on trade was imposed. "With banishment and suspension, no person, boat, merchandise or letter could enter the state issuing the order except at a few well-specified ports or places of entrance where quarantine stations were set up... [and] were subject to quarantine and disinfection even if they carried health certificates issued at the point of departure."15 If necessary, vessels and people could be refused access to either the port or the quarantine stations, with the threat of execution for those who failed to follow the procedures.

A system of forts, towers and observation posts which were within sight of each other was established to help create a cordon sanitaire (sanitary line) around Italy to enforce such bans and suspensions. Armed vessels in the Adriatic and

Artists: Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg

Port of Messina, Italy - Prospectus Freti Siculi, Vol. 4 (1575)

Mediterranean seas were used to stop unwarranted landing.16 Existing forts built on the coasts during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were employed as part of enforcement, allowing the cordon to be rapidly created. As a result, "the quarantine principles established by the middle of the seventeenth century probably changed little thereafter. The cordon sanitaire approach to controlling the geographical spread of plague which was developed in Italy is still used today"17.

Sailor Edward Barlow mentions being denied permission to land at Messina, Italy in 1668 while aboard HMS Yarmouth because of the status of their last port of call. He explains that "the inhabitants being Italians and Spaniards, and they hearing that we came from the Turkey coast, the would not give us ‘prodick’ [pratique - permission to come ashore], or suffer us to come in the town."18 Barlow had been pressed out of the merchant ship Reall Ffrenshipe as a before-mast man and was not privy to the communication between his ship's officers and the officials at Messina, but he notes that the officers were eventually allowed ashore four or five days after arriving and then men were allowed two or three days later.

The independent city-state of Venice extended its cordon sanitaire beyond the borders of Italy. Following the Fourth Crusade in 1204, Venice gained control of the Ionian Islands, Crete, and some of the Greek coastal cities. Here, they "established a network of trading posts. The islands of Corfu, Zante (or Zakynthos),

Artist: Michel Serre

Scene de la peste de 1720 a la Tourette (Marseille) (18th c.)

Cephalonia, and Leukada were incorporated into the Venetian State in 1386, 1485, 1502, and 1684, respectively, and remained part of it until its demise in 1797."19 Venice used some of these locations as buffers to help prevent the plague from reaching their city-state. "Archives show that until the end of the Venetian rule on the Ionian Islands, lazzarettos functioned as protective shields for Venice and transferred responsibility of plague control from Venice to peripheral areas. When there was evidence or even suspicion that plague was present on an island, all links to Venice were immediately discontinued for the duration of the threat."20

Still, the rules of quarantine varied to some degree between different lazaretto locations, even within Italy itself. Historian Carlo Cipolla details the activity of two inspectors - a doctor and a gentleman - sent from Florence, Italy to Genoa, Italy to inspect the Genoese quarantine facilities in 1652. The inspection included their lazaretto, hospital and ships in the harbor. During their inspection, they were surprised to learn that people with ordinary fevers were quarantined, which they "took as further evidence that the Genoese Health Magistracy "'abounded'' in precautions."21 Not long after, Genoa and Florence agreed to establish a common set of rules about how quarantine was to be practiced, which the Genoese said would "eliminate the occasion for the complaints we often hear that more leniency is practiced in Leghorn than here."23

1 Leviticus 13:4-5, King James Bible, 1611; 2 Leviticus 13:46, King James Bible, 1611; 3 John Macauley Eager, The early history of quarantine, Yellow Fever Institute Bulletin No12, March, 1903, p. 15; 4 Neville M Goodman, International Health Organizations and Their Work, 1971, p. 31 5 Paul S. Sehdev, “The Origin of Quarantine”, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2002:35, p. 1072; 6 Guenter B Risse, Seventeenth-Century Pest Houses or Lazarettos, Jan. 1999, p. 25; 7 Proceedings and debates of the Third Annual Meeting of the Quarantine and Sanitary Convention, Baltimore, 1858, p. 259; 8 John Keevil, Medicine and Navy, Vol. 1, 1957, p. 84 & Risse, p. 25; 9 Risse, p. 26-7; 10 Keevil, p. 84; 11 Eager, p. 17; 12 Risse, p. 25; 13 Andrew Cliff, Matthew Smallman-Raynor & Peta Steven, Controlling the Geographical Spread of Infectious Disease - Plague in Italy: 1347-1851, 2009,p. 200-1; 14 Cliff, et al., p. 201; 15 Cliff, et al., p. 202; 16 Cliff, et al., p. 208; 17 Cliff, et al., p. 206; 18 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 157; 19 Katerina Konstantinidou et al, Venetian Rule and Control of Plague Epidemics on the Ionian Islands during 17th and 18th Centuries, Emerging Infectious Diseases Vol. 15, No. 1, Jan 2009, p. 40; 20 Konstantinidou et al, p. 42; 22 Carlo M. Cipolla, Fighting the Plague in 17th Century Italy, 1981, p. 40; 23 Cipolla, p. 46

Bubonic Plague: Mediterranean - Medical Men

A medical position at a lazaretto was not a position most physicians wanted to have. When plague struck on land, the wealthy often headed out to the countryside where the air was better and there were less people so that they could avoid contracting the plague. Many physicians depended on the wealthier class for their patronage, so they followed them. The primary reasons a land-based doctor might remain behind was to have mercy on those who couldn't leave or in response to the duty to their profession. Sea surgeon John Woodall commented in his treatise on the plague that based upon his

Sea Surgeon John Woodall (1639)

experience in the curing of the diseased of the Plague, that it is generally the ungratefullest recompenced of all other diseases, to the poor and hardie Surgeon: Namely, for that hee, when hee hath recovered his Patient, for the most part is loathed, shunned, and avoided, not only of his Friends and Patients, but for his hazard, cost, and care, is so under-valued, that sometimes, but for the persuming to tell his Patient, after hee hath recovered them, that they had the Plauge, hee hazardeth the future losse of their favours, yea, and sometime, under favour, hath his owne house shut up, to make him amends withal.1

However, Woodall went on to say, "I neither can nor will refraine in one good way, or another, to be doing good in my Calling, by Medicines or Advice, both in generall and particular, in that or any other disease, so long as God doth give me life and health, with strength thereunto, maugre [in spite of] the ingratitude of the unworthiest sort of men."2 He goes on by stating that "the excellencie of the Calling of Surgeons should incite them to zeale where they can, as well without reward as for reward, where povertie is, and need requireth."3 Whether this was meant as an indictment of those medical men who left cities undergoing a plague epidemic rather than remaining behind is not mentioned.

Medical historian Guenter B. Risse explains that their "activity made plague doctors de facto 'unclean' and a feared source of contagion. Forced to display a cross that revealed their sospetti [suspect] status, the men remained under constant scrutiny throughout the epidemic, unable to mingle with the rest of the population."4 Risse also points out that many of the plague doctors "were accused of spreading the plague to further their own interests. They also took bribes for non-reporting of cases, trafficked in herbal remedies, and were accused of stealing valuables."5

John Woodall, for all his high-minded call to the nobility of the doctor's profession, didn't exactly write his treatise on the virus without reason. Although he discusses an extensive number of medicines said to be good for treating the plague, providing recipes and recommendations, he

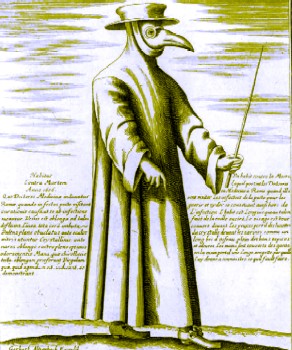

Artist: Gerhart Altzenbach - Plague Doctor (17th century)

also mentions a medicine of his own creation called aurum vitae in many places without explaining how it is made. Lest the reader miss the virtue of his medicine, he ends his treatise by extolling the virtues of the medicine and providing several certificates testifying to its efficacy.6 He indeed worked 'without reward as for reward'.

However, as Risse points out, many of these surgeons "paid with their lives for providing services, while their senior colleagues, on private retainers, left the city for safer and more salubrious [healthy] environments."7 In fact, "their willingness of to assume the considerable risks associated with their professional functions earned them the respect of the authorities who often awarded them citizenship, a coveted recompense to launch a private practice after the epidemic ended."8

Of course, it wouldn't be right to discuss the 17th century plague doctor without at least mentioning the infamous plague doctor costume. "The most striking part of the costume of these plague doctors was the beak mask. The mask had two glass openings for the eyes and a long hollow mouth. In this hollow beak certain herbs (such as mint), dried flowers (roses) and other substances (ambergris, camphor, vinegar) were made, probably to prevent contamination with the plague and to reduce the stench."9 The herbs were designed to perfume and purify the air believed by some to be the cause of the plague and so prevent the doctor from contracting the illness. Modern historian Carlo Cippolla explains that the robe was originally French, being "made of toile-cirée, that is fine linen cloath coated with a paste made of wax mixed with some aromatic substances. 'The sinister costume became very popular, especially in Italy" in the early 1630s and 1656-7.10 However, the author found no evidence of this costume being used after the seventeenth century.

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639, p. 318-9; 2,3 Woodall, p. 319; 4,5 Guenter B Risse, Seventeenth-Century Pest Houses or Lazarettos, Jan. 1999, p. 34; 6 Woodall, p. 367-76; 7 Risse, p. 34; 8 Risse, p. 34-5; 9 Dr. Erwin JO Kompanje, "Plague doctors masks", erwinkompanje.wordpress.com, translated by the author, gathered 10/7/18; 10 Carlo M. Cipolla, Fighting Plague in Seventeeth-Century Italy, 1981, p. 9-11