Sailor's Diet Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Next>>

The Sailor's Diet During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 1

"Without question, equipping and preserving sufficient food and drink on long-distance voyages was intimately tied with the survival of the crew in terms of morale and nutrition and, ultimately, could determine the success or failure of the voyage." (Cheryl A. Fury, "Health and Health Care at Sea", The Social History of English Seamen, 1485-1649, p. 198)

Pirate Edward Low's Men Dining, From

Historie der Engelsche Zee-Rovers (1725)

Food is a topic of monumental importance to all those who made voyages of any significant duration. It had a direct impact on the health and well-being of a crew and was considered a crucial part of those healing from wounds and surgeries during the golden age of piracy.

There is a wealth of information about some of the elements of feeding sailors during this period, particularly what they ate and how they got it. This information exists partially because the navy was involved with the kinds and procurement of food on long voyages and they kept fairly good records. In addition, as sailors expanded the map, they also expanded their diet with some of them taking notes on what they consumed. However, actual preparation and eating of food were apparently considered so mundane that seamen barely mention them in their accounts. Nor are period cookbooks necessarily a reliable guide to food preparation and consumption by sailors since they were written primarily for the upper classes in England. As nautical food researcher Grace Tsai notes, "Cookbooks were often made by and for the elite, because most people couldn’t even read and write.”1 There is some

Artist: Thomas Luny - East Indiaman Hindostan, (1792)

educated discussion about how many sailors were able to read or write (the two skills were taught separately)2, but the recipes found in a cookbook belie their usefulness at sea, where fresh foods were rarely available on ships making long voyages.

This is the fourth of a series of articles which look at food as used by English sailors during the golden age of piracy (1690-1725), broadly dividing them into navy sailors, merchants, privateers and select buccaneers, and pirates. The first article examines how food was used by the body and looked at the perception of healthiness of food provided to sailors. The second article discusses the many ways sailors obtained food while traveling. The third article is a continuation of ideas about obtaining food while under sail, focusing on several formal and informal 'provisioning stations' which were used by sailors. The people and procedures common to all sailors during this period are discussed in the fifth article including an examination of how food was handled, cooked and eaten shipboard.

1 Tyler Allen, "Dining on the high seas", Spirit Magazine, Texas A&M Foundation Website, gathered 9/4/19; 2 See Ed Fox, Piratical Schemes and Contracts, Thesis, 2013, pp. 90-101

Sailors and Food During the Golden Age of Piracy

This article looks at the food consumed by each of the five different types of long-voyage sailors under consideration: navy, navy officers, merchants, privateers/select buccaneers and pirates. It is broadly divided into two parts: the system and officers involved in the supply of food to the sailor and the food they ate.

Artist: Simon de Vlieger - View of a Beach (mid 17th century)

The second part of this article concerns the diet at sea as well as what is mentioned by sailors eating in port. Regular navy sailors - sometimes called before-the-mast men - had a prescribed diet at sea which consisted of specific foods provided in defined quantities on scheduled days. The bulk of this dietary plan was well-established by 1677, long before the Victualling Board was appointed. Several small modifications were made to it during the golden age of piracy, focusing primarily on the food was supplied when ships were sailing in particular locations as well as the issuance of fresh foods while in port.

Being among the worst paid sailors, both in amount and timeliness, navy men were somewhat hampered by a lack of funds when their ship stopped in a civilized port. However, the 'short money' they received to compensate them for being put on limited rations at sea, and the few accounts we have of foods navy sailors bought in port reflect this. English naval vessels rarely stopped except at established locations, typically keeping their before-mast men aboard when they did, so access to exotic foods was more limited than for other types of sailors.

The diet of navy officers is considered next. Although the navy's rules state that all sailors were equal in terms of types of provision on navy ships, officers typically ate much differently than the before-the-mast men when the ship was at sea. To this end, they purchased and supplied their own food for each voyage, sometimes even employing their own cook. Officers were the sailors most likely to keep live animals shipboard to supply them with fresh meat during meals. Since they usually had more money than the regular sailors (although not always), they were able to eat better.

The article next looks at the merchant sailor's diet from the period accounts. There is less information available about their sea diet in the period accounts, perhaps because it was so similar to what the navy ate.

Artist: Antoine Le Nain - Repas de paysans (1642)

However, several merchant sailors talk about what they ate while in port. Here, their sailors diets appear to have been a little more exotic than that of the navy men. Both navy and merchant ships had a fairly robust foreign support network available to supply them with food on land. When possible, they stopped in locations where there were people and organizations which had established supply networks or where the locals were familiar enough with English sailors to be able to provide them with food.

Like other sailors, buccaneers and privateers relied on the same sorts of foods the navy and merchant ships did at sea. They would have a food supply network available when in friendly waters and would probably have had more money to purchase food than merchant or navy sailors, provided they were well sponsored or had been successful in their voyage. There is a marked difference in the food privateers and buccaneers had access to when seeking prey, however. Their operating theaters were in unfriendly waters frequented by the enemy ships they sought and would not have had a dependable food supply. Here, they had to rely on locals in enemy lands willing to supply them, their own success in taking wild game, or the plunder of food from ships and cities they captured. In this way they were like the pirates.

The pirates had more limited access to friendly ports than any other sailor type when they were cruising. A few locations were established either by those seeking to encourage and profit from their marauding or by friendly natives who benefitted from their presence.

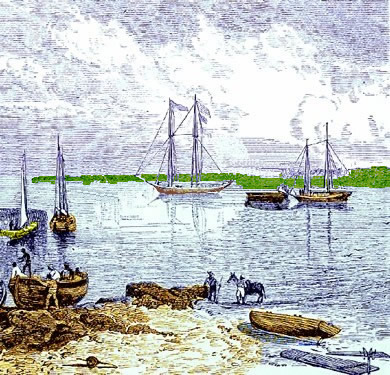

Nassau Harbor, Bahamas, Nassau and West India mail steamship line (1877)

The two main examples from this period were the Bahamas and St Mary's Island in Madagascar. There are also examples of friendly individuals who either sold food or traded it with the pirates, although the pirates would have been at a disadvantage here because they had to trust that the seller would not betray them to local authorities. Still, there are a number of accounts of locals and natives both selling and bartering food with pirates. To discourage this, the monarchy issued an act declaring that those who supported the pirates were "deemed and adjudged to be accessary to such Piracy and Robbery done and adjudged committed ...[and those convicted of such] shall suffer such Pains of Death, Loss of Lands, Goods and Chattels, and in like Manner, as the Principals of such Piracies, Robberies and Felonies ought to suffer"1. So such people risked their lives.

Because of their fear of being caught, pirates sometimes disguised themselves and their ships so that they could land at civilized ports and attempt to procure food. Since many of the pirate accounts focus on their more outlandish and villainous behavior, it is difficult to determine how often such ruses were successful. A few accounts of successful subterfuge exist along with others where local officials caught them at this, details of which can be found here. However, the fact that such things were required indicate how difficult it could be to provision a pirate ship without a structured support network. When pirates did manage to procure a surplus of food from a prize, they often feasted, quickly wasting their bounty.

1 Great Britain and Owen Ruffhead, Statutes at Large, Vol. 4, (1699-1713), 1763, p. 45

Food at Sea During the GAoP

Before going into the details of diets of the different types of sailors, a brief look at what food would survive long-distance voyages is helpful. Looking at each of the five different types of sailors considered here, one might think their diets at sea were as different as the behaviors. Yet, with the exception of naval officers and sick men, nearly all sailors at sea for an extended period had similar diets. Even the officers and sick men were likely to be on this diet after their ship had been on the water for several weeks. This has a great deal to do with the inability to refrigerate foods or gather fresh victuals. Once a ship was a week or two away from land and the fresh foods had been consumed or rotted, the sailor's diet was limited to:

Artist: William Faden (1777)

Dried Foods, such as raisins, beans, peas, maize, rice, flour, oatmeal, pasta and spices.

Preserved Foods, such as those salted or kept in brine (often called 'pickle') including fish, pork, beef, ruminants (particularly goats caught or purchased in foreign ports), and some vegetables.

Long-Lasting Foods, which were somewhat resistant to decay if the ingredients were properly selected, prepared, packed and stowed, including biscuit (very thoroughly-baked hard bread), oil, butter and cheese.

Live food sources including those which could be caught, such as fish, sea birds and turtles, as well as live animals kept penned or stabled shipboard until slaughtered.

The last category sounds like the most appealing source of food, but it was fraught with difficulties. Food caught during the voyage could not be depended upon because the ship to be in a place where there were aquatic animals to catch and the conditions had to be conducive to catching them. These included amenable weather, smooth ship movement and accommodating shipboard activity. Animals brought aboard at the beginning of a journey and penned for slaughter made use of limited space and food on a ship. Officers were given the privilege of keeping livestock on board due to their status, which isn't to say that the regular men couldn't keep them. However, such animals had to be provided with food and water, which, along with space available, were precious while a vessel was at sea for long periods. This was an expense few regular sailors could manage.

Once near land, the variety of foods which could be consumed increased as sailors went ashore for brief periods or were able to buy and trade for food from local vendors in bum boats who came out to meet the ships while close to land. The type of food eaten here depended heavily on how much the sailors could offer in money or trade items to vendors as well as what food was available at the place where the ship had stopped. This would be true for every type of sailor under study.