Dealing With the Deceased Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Dealing With the Deceased in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Burial Location

Image Artist: Howard Pyle (1887)

An important facet of how the body was to be prepared and the burial ceremony performed revolved around where the body was to be buried - on land or at sea.

Based on the sea accounts read from around the golden age of piracy (1672 - 1728) which specify a burial location (or from which can be inferred from the context), about half of the bodies of men who died on a ship at sea were buried on land and half were buried at sea. (See the chart for specific numbers and source references.)

it should be noted that this is a small data sample and a large part of the information comes from the account of naval chaplain Henry Teonge. Although the percentages alone suggest neither burial type was preferred, the data must be examined more closely and the context of the voyage must be considered to glean its true meaning.

Burial Location - Land

Historian David J. Stewart states that "sailors generally preferred interment on land to burial in the sea."1 While this may be true, it isn't stated directly in the any of the golden age of piracy period accounts used in the above data analysis.

By way of proof of his assertion, Stewart points to two burials recorded in the journal of Edward Barlow which he feels would have been more easily performed at sea. The first land burial Stewart mentions involves the wife of a captain who died "in the road" (referring to an often-used sea lane) yet was taken on shore to be buried in a churchyard. This is an

Image Artist: Howard Pyle & Mission

Based on Kidd at Garder's Island

(1887)

extraordinary death which may easily have been treated differently because it was the wife of the captain. The second land burial Stewart mentions is for a ship's carpenter who was rowed several miles away from where the ship was anchored to be buried.2

While the carpenter's burial is an interesting example of a burial requiring some extra effort, Barlow doesn't indicate that land burial was preferred. His matter-of-fact prose regarding the burial of the carpenter in 1676 explains that "when he was dead, they would not let us bury him either in or near the city [of Naples, Italy], for the reason that Protestants are not worthy of burial, or at least not worthy to lie near where any Papist is buried; so we carried him five or six miles by water and buried him near the seaside in a place where few come."3

Counter to this, another burial detailed by Barlow in 1672 explains that, "whilst we were in sight of that island [‘Anyam’] died on board of us a merchant, one Master Cook, which we brought from Bantam along with us, having long been sick of a consumption... And he being dead, had a coffin made for him and was thrown overboard"4. Here it is notable that the crew didn't attempt to bury the man on nearby land, choosing instead to put his corpse into the sea, coffin and all.

Most of land burials found in the samples used in the statistical analysis occurred when a ship was in port or anchored near land. This may have occurred because there was a preference for land burial or it may have been due to other factors. For example, there are accounts of bodies floating behind the boat when not being properly weighted5 and sharks eating the corpses on their way down6, which would have been disturbing events for a crew. There is also the utilitarian fact that a crew may not have wanted to waste shot or other items used to weigh down the body, although this runs counter to notion of the respect that was usually accorded to a corpse.

Barlow's account of the Italians turning the English away from Naples does suggest a problem that was sometimes encountered when attempting to bury a sailor in foreign ports - the local residents didn't always want foreigners in their cemeteries. Sailor Francis Rogers mentions how their supercargo (a person employed to watch over the cargo by its owner on a merchant vessel) was buried at "the back of the town among the Jews and Bannians’ burying place, as permitted by the Governor" in Aden, Yemen7. This suggests that the Arabians wouldn't allow the ship's crew to put the supercargo in their burial grounds. Chaplain Henry Teonge likewise tells of a boatswain dying in December 1675 while they were anchored near Aleppo, Syria.

Artist: Richard C. Woodville

William Dampier (1901)

The preacher "buryed him in the Greeks church yard"8. Teonge faced a similar issue in 1678 in Minorca when Lieutenant Will died. His first entry says we "know not when wee shall bury him." The next entry reveals that they asked for permission to bury him on shore. They received permission to bring him "to a small iland lying in the harbor, which is given to the English to bury their dead uppon; and there wee bury him."9 These examples do suggest a pattern of taking extra trouble to bury corpses on land, even when they weren't wanted there.

While burying Captain Cook, who died "of a sudden" when they sighted land, William Dampier tells of "3 Spanish Indians [who] came to the place where our Men were digging the Grave, and demanded what they were, and from whence they came?"10 The crew's response was they "were bound to Ria Lexa, but that the Capt, of one of the Ships dying at Sea, obliged them to come into this place to give him Christian burial."11

In a rare example of a will drawn up in 1698 by a pirate, Joseph Jones explains "my body I comment [commit] to the earth to be buried in Christian burial at ye discretion of Executors hereafter named, nothing doubting but att the General Resurrection I shall receive the same again by the Mighty Power of God."12 Here we have another suggestion that 'Christian burials' required putting the corpse into the ground.

Curiously, Jewish Law does require land burial, stating "One who puts his deceased in a coffin but does not bury him in the ground, transgresses [a negative commandment] of not letting a dead body sit overnight. And if he put the deceased in a coffin and buried him in the ground, he does not transgress the commandment."13This idea may have been carried into Christian theology. Certainly the concept of "consecrated ground" existed in many Christian cultures at this time.

However, as David Stewart explains, “The 1662 edition of the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer (1762)

formalized the structure and wording of the burial at sea service. This version became the standard form used aboard English and American vessels throughout the Age of Sail and remains the basis for the burial at sea ceremony as it is conducted today."14 Based on this, the Anglican Church clearly recognized burial at sea as a valid Christian burial decades before the golden age of the pirates begin around 1690.

Commenting on the procedures layed out in the 1662 edition of the Common Book of Prayer in 1720, Charles Wheatly explained, "We don’t cast it [the corpse] away as a lost and perished Carcass, but carefully lay it in the Ground, as having in it a Seed of Eternity, and in sure and certain Hope of the Resurrection to Eternal Life". He suggests that it is not the literal words that are important, but the "Sense and Meaning of the Words, [which] may be Shewn from the other parallel Form which the Church has appointed to be us’d at the Burial of the Dead at Sea."

Given the small number of burial accounts, it cannot be denied that there are a surprising number that suggest land burial was worth some extra trouble. Another possible reason may have been that the ocean was an inferior gravesite. While a land burial would put the remains in a fixed location, accessible to the survivors, a sea burial would not.

When a rich merchant died on one of the ships where he was serving, Edward Barlow pointed out that he "was thrown overboard, his honor being washed away, and all his riches affording him no better grave than the wide ocean"15. This hints that sea burial did indeed provide an inferior gravesite.

1,2 David J. Stewart, The Sea Their Graves, 2011, p. 108; 3 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 276; 4 Barlow, p. 223; 5 Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, p. 458; 6 Silas Told, An Account of the Life, and Dealings of God with Silas Told &c., 1786, p. 12; 7 Francis Rogers, "The Journal of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce S. Ingram, editor, 1936, p. 169; 8 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679 Teonge, 1825, p. 100-1; 9 Teonge, p. 270; 10,11 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 113; "14. The Will of Joseph Jones, 9 May, 1698, HCA 1/98, f. 108, Pirates in Their Own Words, Editor Ed Fox, p. 72;13 "Translation:Shulchan Aruch/Yoreh Deah/362", Seif 1, wikisource.org, gathered 10/7/15; 14 Stewart, p. 17; 15 Barlow, p. 100

Burial Location - Sea

Whether there was a preference for land burial or not, it cannot be denied that nearly half of the accounts of burials from ships in our study were performed at sea.

Photo: Wiki User Nilfanion - Monument Depicting Burial at Sea of Sir James Hales

Burials at sea had a long pedigree by the beginning of the golden age of piracy. David Stewart notes that the earliest monument he has found recognizing a burial at sea is for Sir James Hales, "who died while returning to England from Portugal in 1589."1 This monument was likely created at the behest of Hale's family, as it was placed in Canterbury Cathedral. In a way, it highlights the problem of not having any remains to inter for the survivors.

Sir Francis Drake was also famously buried at sea near Panama in 1596 in a "cophin of lead."2 It seems to have been a fairly common occurrence amongst mariners; Alexandre Exquemelin says of William Cammock, who was buried in December of 1680, "In the evening we buried him in the sea, according to the usual custom of mariners"3.

Like Exquemelin, when period accounts mention a burial at sea, they simply record the fact that this was done without providing a lot of detail or explaining the reason for choosing to bury a man at sea. Without supporting information, we are left to infer the reason for this choice.

The most obvious reason for burial at sea seem to be the most likely - it was expedient. Refrigeration was not yet known, so a body could not be cooled for transport and would rot if stored on board a ship.

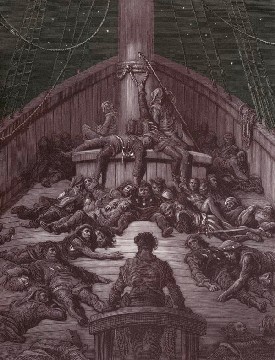

Artist: Gustav Dore

From Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1876)

In addition to problems of smell, putrefying flesh was believed to poison the air and cause illness. As historian Emily Cockayne explains, "Miasmas were thought to drift up from corpses and carcasses, stagnant gutters and ditches, dunghills, privies and any other festering matter."4

When his privateers sacked Guayaquil in 1709, Woodes Rogers noted that his men "would fain have had the boarded Floor of the Church taken up to look amongst the Dead for Treasure, fancying the Spaniards might hide their Money there; but I would not suffer it, because of a contagious Distemper that had swept off a great Number of People here not long before; so that the Church Floor was full of Graves."5 Rogers similarly worried about a hole dug by the Spanish to bury corpses from this outbreak of 'malignant fever'. The hole "was almost fill’d with Corps half putrified. The Mortality was so very great, that many of the People had left the Town, and our lying so long in the Church surrounded with such unhwholsom Scents, was enough to infect us too."6 He believed his fears were realized when later reporting that they had "about 50 men down, and the Dutchess upwards of 70; but I hope the Sea Air (which is very fresh) will make the Climate more healthy."7 This, of course, did not help. More men became ill and at least 12 men were reported dead before the fever had run its course. (Rogers does not detail where they were buried, although it was most likely in Guayaquil. They were left out of my statistical analysis because the men were on land when they died.)

Embalming was one possible way to preserve a body at sea for later interment in the earth. The resourceful 16th century French surgeon Ambroise Paré gives a detailed procedure for embalming in his book.

He begins by removing the organs, "keeping the heart apart, that it may bee embalmed and kept as the kinsfolks shall think fit. Also the brain, the scull beeing divided with a saw, shall bee

Ancient Embalmers (13th c.)

taken out." Incisions are then made "along the arms, thighs, legs, back, loins and buttocks, especially where the greater veins and arteries run" so that they and the blood can be removed to prevent putrefaction. The body is washed using "a spunge dipped in aqua vitae, and strong vineger, wherein shall bee boiled wormwood, aloes, coloquintida, common salt and alum." The open passages are stuffed with a variety of powdered spices which include mint, dill, lavender, rosemary, marjoram, thyme, absinth (wormwood), gentian root, cinnamon, benjamin, myrrh and aloes. Once stuffed, the incisions are sewn and the body is "annointed with Turpentine dissolved with oil of Roses and Camomil, adding, if you shall think fit some chemical oils of spices and then let it bee again strewed over with the fore-mentioned powder: then wrap it in a linnen-cloth, and then in sear-cloths [cerecloth - waxed cloth]."8

Paré's was a very complex procedure! Having a wider period of history to choose from, David Stewart mentions another recipe for embalming which simply treats the excavated cavities with vinegar and packs them with salt. Yet, even he adroitly notes, "Such extended preparations were not usually possible aboard ships at sea, nor would they have been done for most common sailors."9

This may point to the primary reason that burial at sea was 'the usual custom of mariners': trying to preserve a corpse for land burial simply involved too much expense and trouble. Even when a ship were known to be close enough to land to make port, coming to an unscheduled anchor during a journey could be a difficult proposition. It could involve days or even weeks of delay. As a result, the tendency would be not to do so unless it was absolutely necessary.

1 David J. Stewart, The Sea Their Graves, 2011, p. 106; 2 A Full Relation of Another Voyage into the West Indies made by Sir Francis Drake, Printed at London for Nicholas Bourne, 1652, p. 58; 3 Alexandre Exquemelin, This History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 248; 4 Emily Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England, 1600-1770, p. 212; 5 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, p. 98; 6 Rogers, p. 112; 7 Rogers, p. 114; 8 Stewart, p. 108; 9 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p.760; 9 Stewart, p. 108

Burial Location - Pirates

The burial of four golden age of piracy era pirates on land are mentioned in Captain Johnson's second book on the lives of pirates. All of those mentioned are for pirate captains. The most descriptive of these is the account of the burial of Captain John

Artist: Howard Pyle & Mission

Digging A Pirate's Grave, Based on Who Shall Be Captain (1911)

Halsey, which explains that "His grave was made in a garden of water-melons, and fenced in with pallisades to prevent his being rooted up by wild hogs, of which there are plenty in those parts"1. Two of the others pirate burials mentioned are Captains Thomas White2 and John Cornelius3, who Johnson implies were buried in a manner similar to Halsey, although neither burial is described in any detail. The last burial is that of Captain John Bowen who was interred in Madagascar. Johnson notes that he "was buried in the highway, for the priests would not allow him holy ground, as he was a heretic."4

It is significant that all the pirate burials described took place on land, although it is not necessarily surprising. All are descriptions of the burial of a captain, one of the more powerful officers on a ship who may have rated special consideration. A more significant factor, however, is that pirates spent a lot of their time in and around land, much of which would likely have been uninhabited or at least friendly to them because such places would provide a retreat if one were needed. As suggested in the previous section, many of the burials at sea took place on ships where it was not possible to reach land in a timely manner or not sensible to delay a ship's voyage simply to have a burial. However, since land burial seems to have been the preferred method, its accessibility to pirates combined with the likeliness that they might want to show the respect due a captain may explain why they were all land burials.

1 Captain Charles Johnson, The History of the Pirates, 1826, p. 104; 2 Johnson, p. 122; 3 Johnson, p. 165; 4 Johnson, p. 200