Cauterizing Procedure Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Next>>

Cauterizing Procedure During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 3

Cauterizing in the Golden Age of Piracy, Pro and Con, Continued

Con: Trying to Maintain the Correct Temperature

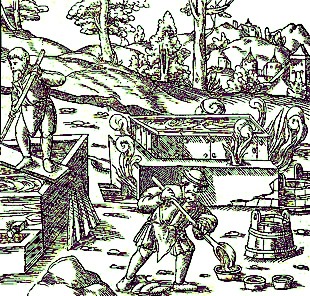

Being able to heat the cautery irons to the proper temperature was also a concern. When discussing the cauterization of a rotten tooth, sea surgeon John Moyle advises the surgeon to

Cautery Irons Heating in Brazier

heat "the small end of your Probe red hot, and so applying it to the hollow of the Tooth to burn or Sear the Nerve"1. Ambroise Paré explains that when a surgeon "should use hot irons, it would be needful to have a forge, and much coales to heat them" to the proper temperature.2

Sea surgeon James Yonge provides the most insight into the problem of maintaining the proper temperature for cauterizing irons. As he notes, "if the Iron be too hot, it either brings off the Eschar [burnt scarred tissue that has sealed the wound] with it, or leaves it loose; if not hot enough, it begets nothing but pain and anguish; these impeachments are so plain, that every one will excuse my Censure. I leave it to the consideration of any ingenious Men, to imagine how difficult it is to heat those dreadful Instruments to the exact degree they ought: and how dangerous when it's time to use them, to delay till they are reduced to it."3

1 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 243; 2 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 20; 3 James Yonge, Currus Triumpalis, é Terebinthô., p. 14

Con: Creating Problems at Sea

Building upon the idea of the problems of heating cautery irons properly for use, Yonge points out that it is a "difficult performance, especially in a Sea-fight"1. Fire was of

Artist: Willem van de Velde the younger

Fireship Attack on the Royal James (1672)

particular concern to those on a wooden sailing vessel. In fact, it was frequently used as a potent weapon against an enemy - entire ships were built to be set fire to and crashed into the opposing ship in a battle. (For more on the dangers of fire on a ship and the treatment of burns, see Treating Burns in the Golden Age of Piracy.) It would be all too easy for an open fire, such as would be lit in a brazier or chafing dish for the heating of cautery irons, to spill and get out of control, especially during the tumultuous environment created by battle.

Sea surgeon John Moyle explains that while cautery at the end of a successful operation might be"a good way were a man on shore... by no means do I like fire on a Platform [the surgeon operated on a lower deck such as the Orlop] in time of Fight; for I remember in one of the last fights we had with the Hollanders, there came a shot in under water, and beat down my Lighter from before me, and battered things on the Platform. And if such a shot should have struck a fire pan [brazier or chafing dish] there it would have hazarded the burning of the Ship."2

When discussing Moyle's surgical techniques, historian John Keevil notes that Moyle may have avoided the use of them due to "[d]ifficulty in heating the irons, except in the galley"3. If they were heated in the galley, it would have been very challenging for the surgeon or his assistants to constantly run back and forth between the surgical platform and the galley in the chaos of battle surgery. They would have little time for that while the wounded piled up around them. This would be further complicated by the irons cooling during their trip.

1 James Yonge, Currus Triumpalis, é Terebinthô., p. 14; 2 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, p. 25-6; 3 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, p. 159

Con: Reopening Wounds

French surgeon Ambroise Paré pointed out another problem with wounds that had been cauterized. "It happeneth that oftentimes the crust being fallen off, the flesh not being well renewed, the blood issueth out as much as it did before."1 He pointed to one of the revered ancient surgical writers, Galen of Pergamon, by way of proof. Paré explained that Galen warned that cauterizing medicines (potential cauteries) "leave the part more bare than the naturall habit requires" when the eschar falls off.2

Artist: Giovanni Battista Crespi

Examining the Bleeding End of An Amputated Leg, From

Miracolo di Aurelia Degli Angeli (1610)

When discussing amputation, Paré observes that in order to stop the new flow from a reopened wound, people before his discoveries relied on cauterization and were "forced to use other causticke and burning Instruments. Neither did these good men know any other course; so by this repetition there was great losse and waste made of the fleshy and nervous substance of the part."3 As a result, "the bones were laid bare, whence many were out of hope of cicatrisation [regrowth of healthy flesh], being forced for the remainder of their wretched life to carry about an ulcer upon that part which was dismembred; which also tooke away the oportunitie of fitting or putting too of an artificiall legge or arme in stead of that which was taken off."4

Surgeon and historian John Kirkup provides a more modern view of the problem that could occur when cauterizing a wound, explaining that in addition to an incorrectly heated iron creating a poor eschar, "the scar might become infected and subsequently cause secondary hemorrhage"5. Infection was not well understood during Paré's time, which may be why he doesn't recognize the problem.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 7-8; 2 Paré, p. 8; 3,4 Paré, p. 156; 5 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 218

Con: Producing Complications

If

Artist: Marco Aurelio Severino

Treating Complications, From Administration de

Efficaci Medicina Libri Tres (1646)

all the other problems with cauterization weren't enough, period authors frequently reported accompanying complications. While discussing the use of heated cautery irons, French surgeon Ambroise Paré pointed out the procedure was sometimes "the cause of a Convulsion, Feaver, yea oft time of death."1 He later warns his readers that "verily of such as were burnt, the third part scarse ever recovered, and that with much adoe, for that combust wounds difficultly come to cicatrisation [formation of healing flesh]; for by this burning are caused cruell paines, whence a Feaver, Convulsion, and oft times other accidents worse than these [occur]."2

Sea surgeon James Yonge echoes Paré and builds upon the list of complications caused by cauterization in amputation, cautioning that it can result in "Fevers, Mortifications [gangrene], Convulsions, loss of substance, ill-shaped Cicatrices [scars on healed wounds], and stumps, the tedious continuation of Eschars, the the [sic] large, and enervating Synovia's [leakage of clear fluids from the wound]; together with a number of less[er] accidents, that are the common and fatal consequences of the usual and most practical ways"3.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 7; 2 Paré, p. 156; 3 James Yonge, Currus Triumpalis, é Terebinthô., p. 3

Con: Cauterizing Is Not a Sure Remedy

The application of both actual (heated iron) and potential (chemical) cauteries was fraught with problems as has been explained. When discussing amputation, French surgery instructor Pierre Dionis declared that there was "no absolute

Artist: Peter Schmidt

Vitriol Recovery, Used to Make Cautery Stones (1580)

Certainty in either of these", referring to actual and potential cauteries.1 He goes on to explain that ligature - tying a strand around a bleeding vein or artery - was a better method and would "stop the Blood more certainly than with Fire [cautery irons] or Vitriol [potential or chemical cautery agents]"2.

One of the primary substances used for potential cauterization was the cauterizing stone. These were made of substances that could burn the skin that were broken up, sometimes combined with liquids and placed on the area to be cauterized. Dionis warns that if the surgeon is not careful in choosing such a stone, he "cannot answer for their Efficacy and Success, they may eat too deep, or too shallow, which may oblige us to lay on others. But they prove yet worse when they are too moist, and have not been kept in a dry place, when they never perform’d so well."3 Dionis suggested that if the surgeon were going to use them, he should make them himself, "that the Chirurgeon may not be deceiv’d" by unscrupulous sellers of such stones.4

Based on the number of pros and cons considered in this section, it is probably clear to most that cauterization was not preferred by many surgeons, particularly sea surgeons. Some of the most scathing summary on the fickleness and undesirability of cauteries come from James Yonge.

The Summary is this; That considering this operation [cautery] to be always terrible and painful; sometimes needless, frequently mischievous, ever difficult to be done Artificially and exactly, often successless, besides the other Objections to which its liable, in common with Corrosives; and that means more successful, more facilly performed [methods, which are] obnoxious to none of the ill consequences hereby, are to be had; (all which are evident,) it [cauterization] ought to be exploded by every one that valueth either his own reputation, that of his Art, or the good of his Patient.5

Nevertheless, both actual and potential cauteries continued to be used throughout the golden age of piracy and long after, so the procedures were still relevant to time.

1,2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 409; 3,4 Dionis, p. 468; 5 James Yonge, Currus Triumpalis, é Terebinthô., p. 14-5