Animal Bite and Sting Wound Treatment Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

Treating Animal Bites and Stings in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 1

Artist: John Singleton Copley - Watson and the Shark (1778)

There are a variety of animal bites, stings and similar wounds found in golden age of piracy sea accounts. Unlike most wounds, which were often mentioned briefly, animal bites and stings were often described in greater detail. This resulted in there being a number of animal attack accounts being mentioned in sea voyage narratives of pirates and sailors from the period. They comprise the first half of this article.

While a wide variety of animal attacks were given in sailor's accounts from the golden age of piracy, many of the animal attacks were not as interesting to the medical men of the time. This is likely because regular bites would have been treated as broken skin wound, the procedure for which can be found in the surgeon's accounts of simple wound care. It was the 'envenomed' wounds which presented a more challenging opportunity for treatment so that was their focus in the medical texts. Procedures designed to manage the humors (bodily fluids thought to control the health of a patient) and medicines to heal the patient were discussed in some detail, which will be presented in the second half of this article.

Animal Attacks

Sailors traveled the world and, as a result, encountered a variety of animals some of whom attacked them. Many types of animals are only cited as attacking men in one or two accounts,

The bull over-drove or the drivers in danger (political cartoon) (1780)

suggesting their attacks were infrequent, probably being caused by unusual behavior by the men coming in contact with them rather than usual behavior of the animal. For example, William Dampier provided an example of a logwood cutter being gored by a wounded bull during a hunt. Because of the limited facilities in their camps in Honduras, the men took the man to a ship's surgeon "who cured him in a little time."1 Other types of animal attacks had wider support in the period literature, suggesting either that animal's danger to the average sailor or the sailor's fascination with or fear of such an animal.

Before discussing which animals attacked in the sea accounts, it is worth noting which animals did not. For example, in the collection of his works, French surgeon Ambroise Paré mentions a large number of animals which he says are venomous including "Toads, Grashoppers, Caterpillars, Spiders, Waspes, Hornets, Beetles, Snailes, Vipers, Snakes, Lizards, Scorpions and Efts or Nutes"2. While some of these appear in the sea accounts used here, many do not.

Two animals of interest are pointedly missing from the sailor's accounts - one of interest to surgeons of the period and the other of interest to modern pirate aficionados.

The animal attack of interest to the surgeons which is not found in the period

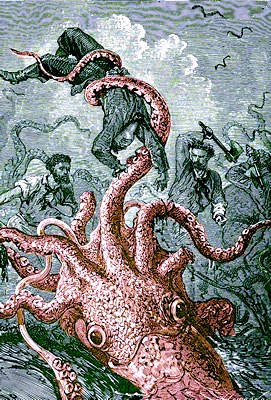

Artist: Alphonse-Marie Adolphe de Neuville

Giant Squid Attacking Sailors, From (Fictional Book)

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870)

sea accounts under study are bites from mad (rabid) dogs. Many surgical writers discuss the cure of rabid dog bites in vivid detail. Paré devotes four chapters of his books to this problem.3 Sea surgeon John Woodall also includes them in his laundry list of animal bites which can cause infection when discussing various treatments for venomous wounds, although he doesn't go into any details specific to or accounts of actual dog bites.4 The fact that this problem is not mentioned in sea-based accounts suggests it was not usually encountered on ships. As a result, the specifics of dog bite cures are not addressed in this article, other than in the generic way they are mentioned by Woodall.

The second type of animal attack not found in the period sea literature are those by giant squids. In fact, trying to find any credible account of an attack on a ship in any period by a giant squid is difficult. (The kraken, an ancient Norse legend, is only mentioned by name in fictional accounts. Some sources point to the first edition of Swedish taxonomist Carl Linneas' book Systema naturae which includes an animal called 'Microcosmus marinus' which might be the same thing, although Linnaes never actually uses the word 'kraken'. Whatever it was, Linnaes must have thought better of including it since that entry was removed in the next edition.5) However, giant squids do exist and legends of their taking ships at sea produced several lurid artists conceptions which make for both good fictional story fodder and exciting images that are placed in the margins of articles on animal attacks at sea.

Having noted the animals not included, let's look at those that were found in the period sea accounts. Among the types of animal wounds mentioned in sailor and pirate narratives are alligator and crocodile bites, different sorts of fish attacks, insect stings, monkey attacks, rat bites, seal bites, shark attacks, snake bites and tiger mauling. The most frequently reported animal attacks by sailors include alligators and crocodiles (which are usually lumped together), sharks, and snakes. Each will be discussed in detail.

1 William Dampier, “Part II: Mr. Dampier's Voyages to the Bay of Campeachy”, Voyages and Descriptions, Vol. II, 1700 p. 100; 2 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 314; 3 Paré, p. 512-5; 4 See John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 45, 71, 84, 120 & 131; 5 "Kraken", wikipedia.com, gathered 10/21/16

Animal Attacks: Alligators & Crocodiles

There are a wide variety of reports found in the sailor's accounts mentioning alligators and crocodiles.

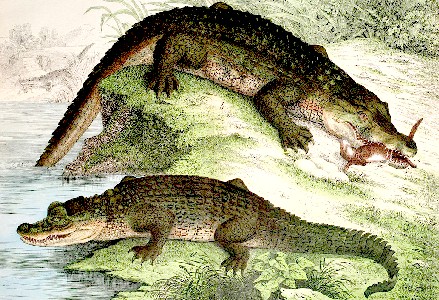

Artist: W.F. Kirby

Crocodile (top) and Alligator (bottom), from Natural history of the animal kingdom

for the use of young people, Plate IV (1889)

Although these are recognized as being different animals, the words for them were sometimes used interchangeably during this period. William Dampier was one of the few sea-authors to explain that they were different creatures, although even he couched some of his comments in such a way that left room for doubt. He noted that crocodiles had slightly longer legs, kept their tail off the ground when it ran "and the Knots on the back are much thicker, higher and firmer than those of the Alligator."1 He also listed several places in the Caribbean where either one or the other were found, but not both.

As for accounts of attacks, we begin with the suspicion of an alligator attack. East India company sailor Edward Barlow reported on a man who had drowned in 1670 off the Malabar coast of India, which occurred "in the beginning of the night and a little dark, he was never seen more, and we judged that some ‘aligator’ had got hold of him when he was in the water, for there are many wild beasts"2.

Several more definite accounts of alligators and crocodiles were reported which usually hinted at their dangerous nature. Sailor Francis Rogers explained that, based on his visit in 1705, alligators could be found in the rivers of Jamaica and were "an amphibious, fierce, and dangerous creature of prey, some 20 feet long or more"3. He further explained, "They will devour a man or take off a limb with ease if in their way. They often go ashore, lurking on the banks of river etc."4 Captain Nathaniel Uring similarly noted that in Honduras, "All their Rivers and Creeks are full of Fish, which also swarm with Allegators, and will seize a Man in the Water."5

While near Java, Captain Alexander Hamilton said there were "many large

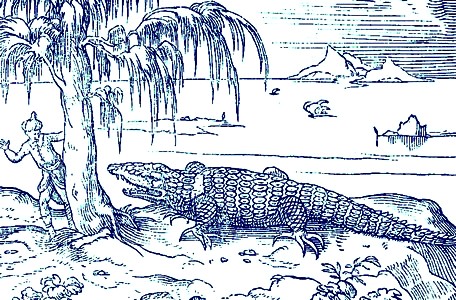

Artist: Andre Thevet -

Alligator Attack, From Cosmographie de Levant, p. 141 (1556)

Crocodiles or Allegators in their Rivers and Marshes, and sometimes they go a Mile or two off to Sea"6. He explained that while he was cleaning his ship, he set up platforms (which he called Stages) for his crew and "when the Water came round the Vessel, and we were plagued with five or six Allegators, which wanted to be on the Stage"7. They fired muskets at them, "but our Ball did them no Harm, because their hard scaly Coat was Shot-proof. At last we contrived to shoot at their Eyes, and we shot at one so."8 As you might imagine, this caused the alligators to leave.

Buccaneer William Dampier warned his readers that the crocodiles at the Isle of Pines (Isla de la Juventud) near Cuba were tricky and "the most daring in all the West Indies."9 He explained that they had a tendency to follow men in canoes and "put their Noses in over the Gunnal [sides], with their Jaws wide open, as if ready to devour the men in it"10. They also 'boldly' came into campsites at night and stole the encamped men's food. "Therefore when Privateers are hunting on this Island, they always keep Sentinels out to watch for these ravenous Creatures, as duly as they do in other Places for fear of Enemies, especially in the Night, for fear of being devoured in their sleep."11

Photo: Tomás Castelazo

An American Crocodile, Photographed in Mexico

Dampier also explained that alligators were not as likely to attack men as crocodiles based on his experience in the Bay of Campeche, Honduras where he said there were only alligators. "I did never know any Mischief done by them, except by accident Men run themselves into their Jaws."12

Dampier gave an example of this which happened to a group of hunters from the logwood cutters camp. "At length an Irish-man [whom he later calls Daniel] going to the Pond in the Night, stumbled over an Alligator that lay in the Path: The Alligator seized him by the Knee; at which the Man cries out, Help! help!"13 His fellow hunters thought he had been caught by Spaniards, which they wanted to avoid, so they failed to come to his aid. Left to his own devices, the man "waited till the Beast opened his Jaw to take better hold... and then snatch'd away his Knee, and slipt the But-end of his Gun in the room of it, which the Alligator griped so hard, that he pull'd it out of his Hand and so went away."14 Daniel was not able to stand, "his Knee was so torn with the Alligators Teeth". He left Honduras for the colonies in order to be cured, returning to Honduras 9 or 10 months later with a limp.

Although he was a bit further afield than most of the pirates sailed, friar Francisco Navarette supplied a very unfortunate story of an alligator attack on fellow friar Lewis Guitierrez in Manila, Philippines in 1653.

He [Friar Guitierrez] was sailing along a Creek, very dangerous because of Alligators; they observ’d one stirring in some particular place, the Indians in the Boat took heart, and endeavour’d to keep on their way, making a noise with their Oars and shouting; but it avail’d nothing, for at the second terrible stroke that the Alligator gave with his Tail, he overset the Vessel, so that they were all cast in the Water. The Indians being more active, and having less hindrance from Clothes, easily got to shore. The poor Religious loaded with his Habit, and not over skilful in swimming, became a prey to that cruel bloody Monster, who fed on him, and he was bury’d in his Bowels.15

Sea surgeon John Atkins reported on a near-tragedy which occurred in Sierra Leone, West

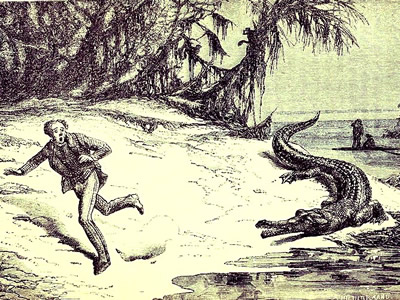

The Englishman and the Caiman, from Reptiles and birds

by Parker Gilmore (1869)

Africa where the pirates often preyed on the slave trade.

[A] Sailor, to avoid walking round a Bay, and being mellow with drinking, would needs cut his way short by wading over a weedy part of it up to his Breast, where the Alligator seized him; and the Fellow having full Courage, ran his Arm down his Throat; Notwithstanding which, the Crocodile loosed, and renewed the Battle two or three times, till a Canoo that saw the Distress, paddled to his Relief, but he was torn unmercifully in his Buttocks, Arms, Shoulders, Thighs and Sides; and had not the Creature been young, must certainly have been killed. The man recovered of his Wounds.16

Atkins doesn't describe the treatment the man received, which is unfortunate. As already noted, non-venomous wounds do not appear to have been of much interest to surgical writers as specific cases at this time, probably because the procedure was similar to any other broken skin wound.

No accounts of pirates being attacked by alligators or crocodiles are recorded (Captain Hook notwithstanding), but Charles Johnson does say in his account of pirate captain Edward England that Madagascar is 'incommodious' due to "the numerous Swarms of Locusts on the Land, and Crocodiles or Alligators in their Rivers."17

1 William Dampier, “Part II: Mr. Dampier's Voyages to the Bay of Campeachy”, Voyages and Descriptions, Vol. II, 1700 p. 75; 2 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 189; 3 Francis Rogers, "The Journal of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce S. Ingram ed., 1936, p. 229; 4 Francis Rogers, p. 229-30; 5 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 242; 6,7,8 Alexander Hamilton, British sea-captain Alexander Hamilton's A new account of the East Indies, 17th-18th century, 2002, p. 421; 9,10,11 Dampier, p. 33; 12,13,14 Dampier, p. 77; 15 Domingo Navarrete, The Travels and Controversies of Friar Domingo Navarrete 1618-1686, 1962, p. 64; 16 John Atkins, A Voyage to New Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 44-5; 17 Captain Charles Johnson, A general history of the pirates, 2nd Edition, 1724, p. 135