Amputation Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

Amputation During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 8

Stopping Blood Loss: Cautery

"[A]fter [the amputation of Captain John Phillip's leg, carpenter Thomas Fenn] heated his Ax red hot in the Fire, and cauteriz'd the Wound, but not with so much Art as he performed the other Part, for he so burnt his Flesh distant from the Place of Amputation, that it had like to have mortify'd, however nature performed a Cure at last without any other Assistance."(Charles Johnson, A general history of the pyrates, 3rd edition, p. 400-1)

Cauterization is the process of burning flesh to stop the bleeding. Our intrepid pirates apparently recognized this, perhaps after watching real surgeons stop bleeding using cauterization, and proceeded to do likewise, if rather clumsily. It is indeed amazing that their cure worked, given that period surgeons were very concerned about not burning the surrounding flesh with cauteries.

There were two different ways of cauterizing at this time: Potential Cautery - burning with acidic medicines and Actual Cautery - burning with red hot cauterizing irons.

Potential Cautery

Copper Sulfate

Pierre Dionis appears to support of the potential cautery after amputation. He proposes using "the Vitriol Button, which is made of a little bit of broken Vitriol [copper sulfate] wrapt up in a little Cotton. We prepare three or four of these, which we lay on the Orifices, at the Vessels which are cut, one after another: This Vitriol dissolving with the Humidity of the Blood, burns and cauterizes wherever it touches, and by the Scar which it makes stops the Blood".1 John Atkins advises that "If ever you should be engaged to their [potential cautery] Use, the Pul. Vitriol. Roman. [powdered copper sulfate] is the readiest and the best: A thick Pledget or Button is first to be pressed out of warm Ol. Terebinth. [spirit of turpentine] and when sprinkled or dipped in this Powder, applied to the Mouth of the Artery."2

John Atkins quickly dismisses potential cautery "as their Effects are more tragical; they gnaw and corrode on the Ends of the Nerves and Tendons, and so insinuate and spread their Malignity, that you never fail of extreme Pain from them, a large Synovia [release of fluid], and too often Fevers, Convulsions and Death".3 Dionis warns that the "Scar [created by a potential cautery] shares the same Fate with that produced by Fire, for coming to fall off, the Blood may escape out... and the Chirurgeons which make use of this way ought to have these Buttons ready every time they dress the Patient, in order to apply them whenever the Blood issues out."4 Ambroise Paré notes that no "causticke [can] be applied to nervous bodies, but that this horrid impression of the fire will be presently communicated to the inward parts, whence horrid symptomes ensue, and oft times death it selfe."5 Richard Wiseman adds, "To apply Escharoticks [mild caustics] to the ends of the Nerves and Tendons newly incised, causes great pain, weakens the Part, and makes way for Gangrene; it not being likely you can so apply them to the Artery, but that you must burn the Parts about, which are, as I said, the Nerves & c."6

Actual Cautery

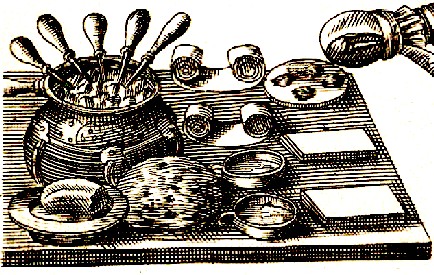

Johannes Scultetus' Amputation Dressings from De L'Arcenal De Chirurgerie, p. 70 (1672)

Actual cautery was a different matter according to some of the period surgeons. Richard Wiseman maintained that when he was "[a]t Sea ... We stopt the Flux of blood by actual Cautery, and the Wound digested and cured without any ill accident."7 Wiseman was a great proponent of using cautery irons following an amputation. He explained that, "in the heat of Fight it will be necessary to have your actual Cautery always ready, so that will secure the bleeding Arteries in a moment, and fortifie the Part against future Putrefaction [decomposition].".8 As you can see in amputation dressing table at right, the irons are sitting ready in a basin of hot coals.

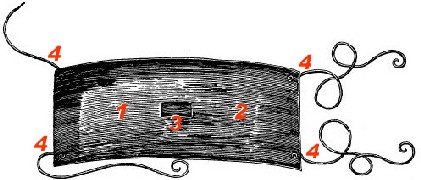

A Cautery Shield taken from Jacques Guillimeau's "The French Chirurgerie", p. 31

The description on page 30 reads: " 1,2 The croockede plate, whihc must be religatede

thwarte over the bodye: the perforation whereof is noted with

3, which must be collocated, on that place where we desire to make an apertione.

4,4,4,4 Little Ligamentes, which houlde faste the plate on that place, &

must be tytede on the bodye ."

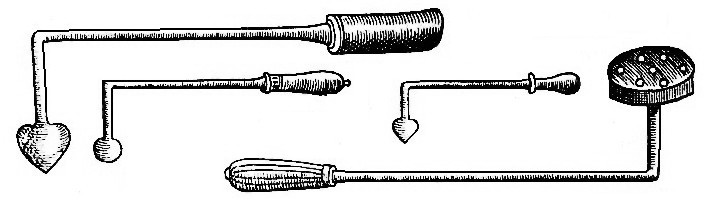

For the cautery irons themselves, Pierre Dionis explained that surgeons "heated red hot their actual Cauteries, of which some were shap’d like a Button, others like an Olive, and a third sort like a Platin; they apply’d them red-hot to the Orifices of the Vessels as soon as the Member was separated".9 The Cautery Irons Mentioned can be seen below. Top left is a large Olive Cautery; directly below it is a Button Cautery; to its right is a small Olive Cautery. The large cautery on the bottom right is a Platin Cautery. John Atkins explains that to "use the Cautery aright, there should be a flat Iron Plate to preserve the adjacent Parts, with a Hole thro' the Middle, made fit to receive the End of the heated Button on the Artery."10 An example of a Cautery Shield from The French Chirurgerie can be found above left with the explanation taken from the book's author.

Several Cautery Irons used in Amputation - including two Olive Cauteries, a button cautery and a Platin Cautery

Several Cautery Irons used in Amputation - including two Olive Cauteries, a button cautery and a Platin Cautery

Taken from

"A Discourse of the Whole Art of Chyrurgerie" by Peter Lowe, p. 92 (1634)

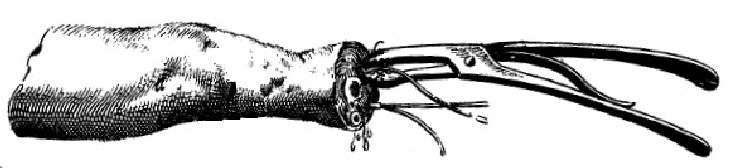

In a case from his memoirs, John Moyle suggests a method for cauterization after amputation. "I took the Cauterizing Button which was made red hot, and touched the ends of the large Arteries, to stop the bleeding, so clapt a dry Dossel of Stupa Sultilis to the end of the Bone, to defend from gleet [running fluid] and keep in the Marrow."11 Wiseman's adds a step, explaining that he after "cauteriz[ing] the Artery, we do

Cautery Irons being heated during an arm amputation. From the book

"De Gangrena et Sphacelo" by Willhem Hildanus (1617)

then touch the end of the Bone, it hastening the Exfoliation [casting off necrotic bone matter].

"12 Atkins warns that if the cautery irons were "not hot enough, it makes no Eschar [dead scarred skin], giving only unnecessary Anguish to the Patient: And on the other Side, if too hot, it then makes an Eschar indeed, but separates and loosens it at the same Time, the Security being intended being either way equally eluded. But this is an Inconvenience that may be obviated by a quick or slow Application, as the Surgeon shall judge to the Degree of Heat in his [cautery] Button."13

Many surgeons during this time period argued against the use of cautery irons after amputation. The first to do so was Ambroise Paré. Paré was largely responsible for revolutionizing this part of amputation. His argument is strong, pointing out several deficiencies with cauterization after amputation.

"Let us come now to Reason

Now so it is, that one cannot apply hot irons but with extreame and vehement paine in a sensible part, void of a Gangreene, which would be the cause of a Convulsion, Feaver, yea oft time of death. Moreover, it would bee a long while

Cautery Irons and a Brazier

from

afterwards before the poore patients were cured, because that by the action of the fire there is

made an eschar, which proceeds from the subject flesh in stead of that which hath beene burned, as also the bone remaines discovered and bare; and by this meanes, for the most part there remaines an Ulcer incurable. Moreover there is yet another accident. It happeneth that oftentimes the crust being fallen off, the flesh not being well renewed, the blood issueth out as much as it did before."14

In a modern day analysis of naval Medicine, John Keevil explains that, "it is indeed hard to find any evidence of that 'searing'… being used in ships. Difficulty in heating the irons, except in the galley, may have contributed to this exclusion, but the close relations between the ship's surgeon and his patients went far to produce a revulsion from an inhuman method. [John] Moyle used two ligatures [the above cauterizing example being from his land practice], depending on tow buttons soaked in styptic and on pressure when the dressings were applied, methods identical with those in use by William Clowes at the time of the Armada."15

So it would appear that neither potential cautery nor actual cautery were preferred post-operative methods to stem bleeding arteries following an amputation while shipboard. This brings us to the third method to stop bleeding after amputation.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 408; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 121; 3 Ibid.; 4 Dionis, p. 408-9; 5 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 156; 6 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 452; 7 Ibid,; 8 Ibid, p. 452-3; 9 Dionis, p. 408; 10 Atkins, p. 122; 11 John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, p. 120; 12 Wiseman, p. 453; 13 Atkins, p. 122; 14 Paré, p. 7; 15 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, p. 159

Stopping Blood Loss: Ligatures

As mentioned, Ambroise Paré was one of the first prominent surgeons to speak against cauterization. Paré also discovered that medicines worked better than cauterization in gunshot wounds and was largely responsible for discovering that they weren't poisonous by nature and thus didn't require cauterization. (You can read about his work on medicines to replace cauterization in gunshot wounds on this page and about his discoveries regarding the lack of inherent poison in such wound here.)

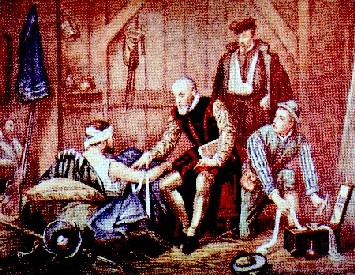

Ambroise Paré Treating the Wounded by Eduoard Hamman

In place of cauterization to stem blood flow, Paré recommended ligatures. These ligatures were not like those used as a tourniquet, but small, often silk, strands that were tied around severed arteries and veins. Paré explained that the "Veines and Arteries [are to] be bound up as speedily and streightly [tightly] as you can; that so the course of the flowing blood may bee stopped and wholly stayed."1

He goes on to explain how this method works. He first suggests "taking hold of the vessels with your Crowes beake [Crow's Bill Forceps]... The ends of the vessells lying hid in the flesh, must be taken hold of & drawn with this instrument forth of the muscles whereinto they presently after the amputation withdrew themselves, as all parts are still used to withdraw themselves towards their originalls. In performance of this worke, you neede take no great care, if you together with the vessells comprehend some portion of the neighboring parts, as of the flesh, for hereof will ensue no harme; but the vessells will so bee consolidated with the more ease, than if they being bloodlesse parts should grow together by themselves. To conclude, when you have so drawne them forth, binde them with a strong double thred."2

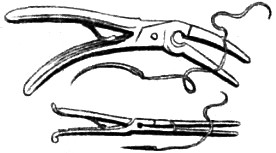

Spring forceps shown with ligature taken from Pierre

Dionis'

A course of chirurgical operations, p. 403

Pierre Dionis refined the explanation, advising the use of forceps with "a pair of Nippers, with a Ring to close them, which we call a Valet á Patin: They slip on the Instrument as far as to the Artery, a thread prepar'd and noos'd and fasten it with a double Knot; and that is may not be shov'd off the end of the Artery by the continual Pulsations of the Arterial Blood, there is to be at one of the ends of the Thread a threaded Needle, which they run through across the Body of the Vessel, after which they secure the Ligature by tying some Knots."3

Based on his instrument drawing (at left), he may have been referring to a spring, not a ring.

John Atkins had a slightly different take on the ligature. He explained that while using ligatures had "Pre-eminence in Practise, neither carrying the Dread a Cautery does, nor the Insecurity mentioned of Astringents: it can only be unsafe, when by a mistaken Method the Knot is slipped over the Forceps, (instead of piercing the circumjacent Flesh,)"4 Atkins had found that the pulsing artery had a tendency to push the ligature off. So he suggested sewing the artery in addition to tying it closed.

Using spring forceps ot extract and artery taken from Jacques Guillemeau's

The French Chirurgerie, p. 29

"First, a loosening of the Turniket being made, and the Artery discovered by its Impetus, you immediately lay hold of it with a Spring Forceps".5 Notice that he is using the pulsing blood to find the Artery, clamping down with the spring forceps once it has been discovered. The spring in spring forceps would force them closed. Atkins goes on, "...having the Arterial Needle ready armed with double Silk, and waxed, you are to pass it round, taking up a small Circle of Flesh [of the artery], nigh [near] the Mouth of the Artery, then comprehending a very small Linnen Compress between that and the Tie, you make fast with a close double Knot."6

Once the ligatures were tied and the wound closed, "the ends of a ligature were left long, protruding out of the wound. After a while the tightly tied end of the artery or vein necrosed and sloughed off from the healthy tissue to be withdrawn with the ligature when it was pulled out of the wound."7

1 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 150-1; 2 Ibid.; 3 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 409; 4 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 122-3; 5 Ibid., p. 123; 6 Ibid.; 7 David MacKenzie, "The History of Sutures," Med Hist. 1973 April; 17(2): p. 166

Stopping Blood Loss: The Cross Stitch

James Handley, a British

Royal Naval Surgeon suggested that there was a better way for ship's surgeons to stop blood loss which would save them a step. He recommended a "cross Stitch be made directly over the Buttons [small round pieces tow or

The Capture of Puerto Bello in 1739, by George Chambers, Sr (1836)

lint soaked in astringents and Spirit of Turpentine] (that are on the ends of the Arteries) and pulled tight and equal, and the Stump also covered with small Pledgets [round lint bandages] armed with Restringents [astringents], and two large ones over all, no Hemorrhage need to be feared, though no Ligature of the Arteries be made at all."1 This cross stitching and bandaging process was widely used to close the stump and begin the healing process as we'll soon see. Handley was using the cross stitch to also press buttons of tow against the ends of the arteries, likely preventing their bleeding though this direct pressure.

He claimed "in all the Sea-Fights which I have been in, (which have been pretty many) I never used any other Method and never had any Hemorrhage attending, nor succeeding it".2

As interesting as his procedure might be to sea surgeons, his reason for doing it was even more telling. While he recognized that using ligatures to tie the arteries off was "a very sure and secure Way, if you have the Time; but in a Sea-Fight, attended with great Confusion and a Multitude of Business, and where you must operate by Candle-light; a Ligature of the Vessels is not so practicable, and takes up too much Time".3 One can readily imagine trying to find the arteries in the dim candle light, keep hold of them as the beating of the heart cause them to pulsate and then tie them off with a thin silk strand. Other sea surgeons mention the need to quickly finish amputations and move on to the next unfortunate victim.4 However, you can't help but wonder how painful it must have been to draw the cross stitch tight enough to hold the buttons of tow material firm against the severed arteries. Perhaps the excitement of battle heightened the patient's adrenaline sufficiently that he didn't notice.

1 James Handley, Colloquia Chirurgica: or The Art of Surgery, p. 142; 2 Ibid. p. 141; 3 Ibid. 4 See John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 55