Plague Quarantine Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Maritime Quarantine For Plague, Page 1

“The distemper [the plague] will not spread at sea, more than on shore, without a concurrent disposition in the air; and, by early precautions in the beginning, its progress may perhaps be stopped more effectually on ship board than on shore.” (Patrick Russell, A Treatise on the Plague, Vol. 2, 1791, p. 350)

Artist: Claude-Joseph Vernet - A Calm at a Mediterranean Port (1770)

Although ships had a great deal more freedom to move between ports during the golden age of piracy than they do today, they also faced the problem of quarantine, a policy which had its roots in the fifteenth century. The practice was particularly popular in ports along the Mediterranean Sea, where the plague was regularly encountered during the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries and, to a lesser extent, in the eighteenth century. As a result of commerce between the eastern coast of France and the Mediterranean, organized quarantine measures were employed there as well. In addition quarantine measures were sporadically taken for ships coming to England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. However, these were nowhere near as well organized or consistent as those used in France and the Mediterranean cities.

This first part of this article examines maritime quarantine, beginning with a look at the terms required to understand it and the disease it was designed to prevent - bubonic plague. It then briefly looks into the rules establishing quarantine, how the lazarettos worked, where maritime quarantine was served, and ways sailors and officials found to cheat on the system. The last section discusses the locations pertinent to maritime quarantine as described by sailor from around the period, including several Mediterranean lazarettos as well as some thoughts on quarantine as used in England. .

Terms

There are a number of terms associated with quarantine during the golden age of piracy, many of which are unfamiliar today and all of which have interesting backgrounds.

The first is the word quarantine, a term which most people associate with a period of

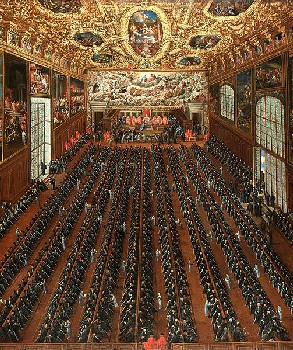

Artist: Joseph Heintz

The Grand Council of Venice (17th c.)

isolation imposed on people with contagious illnesses. However, it had a more specific meaning during this time which is relevant to the way it was usually performed. 'Quarantine' comes from the Italian word quarantino, which is derived quaranta ('forty'). This refers to the 40 day period established in the city-state of Venice in 1403 which was how long people were to be isolated from the local population to make sure they didn't have the plague.1 In establishing quarantine procedures, the Great Council in Venice initially passed a law in 1377 requiring a 30 day period of isolation called a trentino, but it was eventually modified to 40 days. Speculation about the significance of the forty day period usually focuses on the biblical significance of 40 days - the number of days of Lent, how long Moses was on Mount Sinai, Jesus' stay in the wilderness or the length of time in which the great flood occured.2 Some authors disagree, suggesting that the forty day quarantine "probably had a medical origin, which is derivable in part from the doctrine of critical days; for the fortieth day, according to the most ancient notions, has been always regarded as the last of ardent diseases, and the limit of separation between these and those which are chronic."3 Regardless of the reason forty days were chosen, they are at the root of word quarantine.

The structures used to quarantine incoming passengers, sailors and goods were called lazarettos. The Venetian senate first ordered the use of such a structure in August of 1423. They identified a building on the small island of Santa Maria de Nasova (Nazareth) in the Venetian lagoon off the

Artist: Claude-Joseph Vernet

A Calm at a Mediterranean Port (1770)

Lido for this purpose. "Formerly a hospice for pilgrims returning from Nazareth in Palestine, this twenty-bed shelter known as Nazaretto was now to be reserved for the detention of foreign traders who were sick or suspected of carrying pestilence. Here they and their goods were to be kept away from the port for the traditional forty days."4 As the concept of quarantining incoming vessels gained popularity, "similar facilities in fifteenth-century Italy were similarly first known as nazarettos, but the term changed to lazarettos or Lazar houses because their new segregating function was equated with that commonly employed with lepers."5

Of course, quarantining every vessel that came into port was difficult and pointless in cases where a ship had already performed quarantine at another city. To facilitate shipping, a system was set up with this problem in mind. Letters could be issued by a city where a ship had completed its quarantine which could then be used to allow them access to other ports without having to perform a full forty day quarantine. During the golden age of piracy, permission to enter a city was called pratique, an early 17th century French term which comes from the Latin word practica (or practice). John Worlidge defined this in his 1726 dictionary: "PRATIQUE or PRATTICK - a Licence to Traffick or Trade granted to the Master of a Ship, in the Ports of Italy, upon a Bill of Health, i. e. a Certificate that the Place whence he came is not annoy’d with any infectious Disease."6 Such documents have an ancient origin. During the great eastern Roman plague of 541-2, Emperor Justinian allowed people entering Constantinople from infected areas to "be 'purified' in special places arranged for the purpose and afterwards given a ‘health certificate’ (passeport de sante)."7

The disease for which the Mediterranean maritime quarantine was created was the bubonic plague often just referred to at this time as 'the plague'. Seventeenth century sea surgeon John Woodall says the word 'plague', "is derived from the Latine word Plaga, which is a wound, a stripe, a stroake or a hurt"8. Just as Woodall notes, one of the definitions of the Latin word plaga is" "A blow, a stroke, a stripe, a wound"9. In a more colorful, modern explanation, Katerina Konstantinidou expands upon this, explaining, "The disease got its name from the deep purple, almost black discoloration of infected persons caused by subcutaneous hemorrhages."10

1 Neville M Goodman, International Health Organizations and Their Work, Ch 2, 1971, p. 29; 2 Paul S. Sehdev, “The Origin of Quarantine”, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2002:35, p. 1072; 3 Justus Friedrich Carl Hecker, The Black Death in the Fourteenth Century, 1833, p. 168; 4,5 Guenter B Russe, Seventeenth-Century Pest Houses or Lazarettos, Jan. 1999, p. 26; 6 John Worlidge & Nathan Bailey, Dictionarium Rusticum, Urbanicum & Botanicum, Vol. 2, 1726, not paginated; 7 Goodman, p. 29; 8 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639, p. 323; 9 C. D. Yonge, Phraseological Latin-English Dictionary, Part II, 1856, p. 395; 10 Katerina Konstantinidou et al, Venetian Rule and Control of Plague Epidemics on the Ionian Islands during 17th and 18th Centuries, Emerging Infectious Diseases Vol. 15, No. 1, Jan 2009, p. 39

Purpose of Maritime Quarantine

The purpose of maritime quarantine in the Mediterranean was to prevent bubonic plague from spreading. This quarantine system initially focused on prevention on land, keeping the ill and anyone living in close proximity to them segregated from the healthy. Beginning in the 14th century, governments began to understand that the bubonic plague was somehow being spread by ships and took steps to establish quarantine stations outside of cities where incoming vessels could be isolated and their men and cargos could be either proved to be healthy or put into quarantine before they were allowed to enter the city and unload their cargos.

Artist: After Allan Ramsey

Physician Richard Mead (18th c)

English physician Richard Mead wrote a widely circulated and respected treatise on the plague which said that "CONTAGION is propagated by three Causes, the Air; Diseased Persons; and Goods transported from infected Places."1 He explained the stopping the plague required two things: "The preventing its being brought into our Island; And, if such a Calamity should happen, The putting a stop to its spreading among us."2 To stop the plague from being brought to England, he recommended a system of quarantine stations and buildings, cleansing of ships and their cargos and even destruction of clothing and cargos suspected of being tainted. To prevent its spread once the plague reached English shores, Mead recommended the same system of isolation used during the Great Plague of London in 1665: "any House [which] was infected, to keep it shut up, with a large red Cross, and Lord have Mercy upon us [posted] on the Door; and Watchmen attending Day and Night to prevent any one's going in or out"3. Although England never built lazarettos like those in Mediterranean ports, they did set up a quarantine system which involved keeping ships at anchor in isolated areas to perform quarantine.

The effectiveness of this system was quite hit-and-miss, although it was believed to be the best defense. Writing in 1791, Scottish surgeon Patrick Russel explained, "Italy has been less frequently visited [by the plague] since the establishment of quarantines and lazarettos in the maritime towns, though from the impossibility of always preventing breach of rules, they have not always proved infallible defences"4. However, as modern author Neville M. Goodman points out, "in the absence of knowledge of the modes of transmission of the pestilential diseases- or even of any clear distinction between them - as well as of rapid and reliable information of their occurrence, successes of the eighteenth century quarantines must have been largely fortuitous."5

1 Richard Mead, A short discourse concerning pestilential contagion, 1720, p. 1; 2 Mead, p. 21; 3 Mead, p. 32; 4 Patrick Russell, A Treatise on the Plague, 1791, p. 327; 5 Neville M Goodman, International Health Organizations and Their Work, Ch 2, 1971, p. 34