The Politics of Sea Surgery During the GAoP Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Next>>

The Politics of Sea Surgery During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 3

Macro-Politics: The Barbers and the Surgeons

The relationship between barbers and surgeons originally sprang from prohibitions put in place by the Catholic church on the medical work of members of the church.

Dominican Doctor Taking Pulse, From

Medical Miscellanea by Isaac Israeli

U. Penn Rare Books (c. 832 - c. 932)

This began in the 12th century with Pope Alexander III's edict from the Council of Tours in 1163 which stated that the church abhorred bloodshed.1 Pope Innocent III expanded upon this proclamation during the fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215. As a result, the monks who had been performing surgery were directed to stop doing so. In an effort to provide medical services to the poor, they trained their barbers to do surgery since it "did not violate the ecclesiastical prohibition of shedding blood"2. The monks also recognized that the barbers "were clean by trade as well as accustomed to sharp tools, [and so the monks] made use of them when it became necessary to pass on their knowledge of simple surgery along with techniques of letting blood."3

The barbers became more skilled in the art of surgery and "were first organised as a religious guild"4. Theirs was the first medical organization. "The earliest surviving record of their existence is dated 1308, but it has been suggested that there was a guild of barbers in London before 1180".5 A variety of provincial barbers guilds were formed in the fourteenth century in towns such as Exeter, Norwich, Lincoln, Bristol, York, Newcastle, Edinburgh, Dublin, Salisbury, Chester, Durham, Southampton, Ipswich, Hull, Worcester, Reading, Beverley, Oxford, Hereford, St. Albans, Gloucester, Aberdeen and Glasgow, Limerick and Cork.5 The London company eventually divided itself into "two distinct sections, that of the barbers and that of the barber-surgeons, who were only barbers in name and gradually dropped the prefix."6 The barbers were granted a royal charter by King Edward IV in 1462. Their charter of incorporation "regulated the practice of surgery, but apparently said nothing about barbers."7

A group of surgeons banded together in the 1300s. "The guild or Fellowship of Surgeons of London was formed ...probably as an outcome of the Act of Parliament of 1363 which required every man to belong to a guild."8 Theirs was a small, exclusive group, from which royal surgeons were chosen to tend to the King. Members were to be examined by a Master in Surgery. They joined with the physicians to form "a cojoint college in May, 1421."9 However, this College of Medicine and Surgery appears to have ceased to exist by by 1424.

In 1493, the Fellowship of Surgeons was united with the Barber-Surgeons guild.10 "Who initiated the agreement is not known, but an agreement was made ...to control Surgery in London."11 Historian John Keevil says that the merging of the surgeons and barbers was 'inevitable' due to the barber-surgeon's guild's "growing strength [which was such that] it should ultimately draw the Surgeons' Guild into its organization."12

In 1511, the third year of Henry VIII's rule, his 11th Act declared that "surgeons and physicians were obliged to have a licence to practise from the bishop of London or the dean of St.

Paul's"13. However, the barber-surgeons and unlicensed practitioners seem to have had a

Artist: Hans Holbien the Younger -

Henry VIII and the Barber Surgeons in 1540

freer hand; in 1523, the 14th & 15th years of Henry's rule, the 8th act passed which spoke "in favour of men and women who understood the 'nature of herbs, roots,

and waters,' who, it was enacted, were not to be interfered with"14.

The alliance of the Barber-Surgeons guild and the Fellowship of Surgeons was formally recognized when parliament passed the 12th act during Henry's 35th year of reign in 1540, granting a charter to the combined group which then became known as the Company of Barber-Surgeons. Under this act, "No surgeon was permitted to shave and no barber to practice surgery, except tooth-drawing."15 Rory McCreadie says that advantages accrued to both groups. "The advantage for the Company was a matter of prestige, for the Fellowship was a more select group of top-flight surgeons. The Fellowship on the other hand had the advantages of an incorporated livery Company with clout and valuable assets of its own halls."16

However, this Act only extended to London and areas within one mile of it.17 Historian Iris Bruijn comments that "in the countryside, surgeons could practise more generally, together with apothecaries, empirics, and physicians. In fact, according to English common law, anyone could practice medicine as long as the patient consented."18 Sea surgeons obviously fell well outside the jurisdiction of the Act once they left London.

The alliance between the barbers and surgeons was never an easy one. Keevil explains that "conflicts between the rival bodies had been frequent; as a consequence, the Court at Guildhall had in 1376, 1410 and 1424 to confirm the barber-surgeons' right to practise surgery."19 Historians Albert Lions and Joseph Petrucelli divide surgeons into two basic types (and further into various grades within that).

Artist: David Teniers the Younger

Barbers Performing Surgery (17th Century)

‘True’ surgeons concerned themselves with major operations: suture of hole in the intestines, removal of tumors, plastic operations on the lips and nose, repair of rectal fistulas. The barber-surgeons were wound doctors who also performed bloodletting, cupping, the extraction of teeth, and the management of fractures, dislocations, and external ulcers.20

McCreary says the by the English Civil war in the mid 17th century,

the Surgeons and the Barbers were at best ignoring or at worst fighting one another. The standard of surgery was better, but the Surgeon looked down upon the Barbers as poor cousins and as a millstone. The Barbers thought themselves betrayed by the Surgeons of the Barbers’ Company and pushed to one side by the Surgeons of the Fellowship. It was not a happy Guild.21

This was due in part to the serious rift in expectations between the barbers and the surgeons. "All the surgeons’ endeavours to improve their standing, together with the advance in their craft, tended to widen the gap between themselves and the barber members of the guild."22 Things got so bad that "in 1684, a group of surgeons petitioned the king for permission to found a separate company."23 However, the surgeons did not manage to extricate themselves from their relationship with the barbers until after the golden age of piracy in 1745.

1 Gilbert R. Seigworth, "A Brief History of Bloodletting: Bloodletting Over the Centuries", Gilbert R. Seigworth, M.D.PBS.org, gathered 8/24/14; 16 Basil A. Pruitt, Jr., "Combat Casualty Care and Surgical Progress," Annals of Surgery, Vol. 243, Number 6, June 2006. p. 716; 3 Joan Druett, Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail, 2000, p. 134; 4 Iris Bruijn, Ship's Surgeons of the Dutch East India Company, 2009, p. 29; 5 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume I – 1200-1649, 1957, p. 35; 6 Keevil, p. 36; 7 Bernhard Wolf Weinberger, An Introduction to the History of Dentistry, Volume 1, 1948, p. 235; 8 Keevil, Vol. I, p. 35; 9 Keevil, Vol. I, p. 38; 10 Sir Cecil Wakely, Surgeons and the Navy, transcript of Thomas Vicary Lecture delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons in England, 11/14/1957, p. 268; 11 Rory W. McCreadie, The Barber Surgeon's Mate of the 16th and 17th Century, p. 12-3; 12 Keevil, Vol. I, p. 36; 13,14 Charles Knight, Knight's Encyclopædia of London, 1851, p. 363; 15 Weinberger, p. 235; 16 McCreadie, p. 13; 17 McCreadie, p. 14; 18 Bruijn, p. 30;19 Keevil, Vol. I, p. 36; 20 Lyons, Albert S. and Petrucelli, R. Joseph II, Medicine: An Illustrated History, 1997, p. 454-5; 21 McCreadie, p. 27; 22 Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, 1958, p. 153; 23 Keevil, Vol. II, p. 154

Macro-Politics: Making Surgery 'Learned'

“Physic, which included natural philosophy and whose practitioners would have first studied the arts curriculum at university, provided surgery with its theory, whilst unlearned surgery was seen as concerned with practise alone.” (Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, 1992, p. 223)

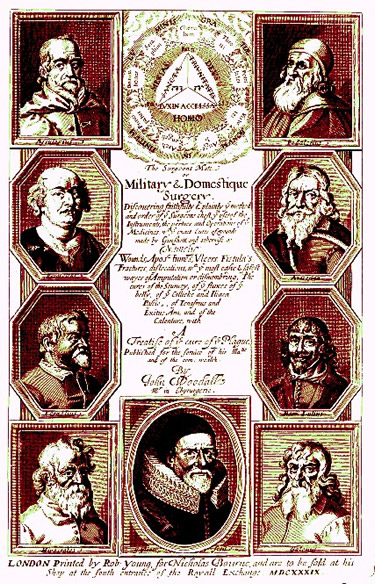

Some surgeons wanted to make their craft worthy of the consideration and prestige which the College of

Frontispiece to John Woodall's the surgions mate, Featuring Many of

the Revered Classical Medical Authors. Clockwise from Top Right:

Mythical Greek Physician Podalirius,

Persian Physician Avicenna.

Majorcan Ramon Llull, Galen of Pergamon, Woodall, Hippocrates,

French Physician Jean Fernel, German Physician Paracelsus

and Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine. (1639)

Physicians enjoyed. As a result of this, historian Andrew Wear explains that during the Renaissance, "there was renewed emphasis on making surgery learned"1. This was done, in part, by surgical authors citing the relevant passages found in the 'classical' medical authors like Hippocrates, Galen and Celsus and others.

While the physicians usually wrote in Latin - the 'learned' language - educated surgeons such as Ambroise Paré, John Woodall, James Cooke, Thomas Brugis, Richard Wiseman and John Atkins wrote in their mother tongue. Many of their books contained explanations of some of the theory behind 'learned' medicine such as the proper uses of surgery, diet and medicine and how the seven natural things in man's body (humors, temperaments, elements, parts, faculties, actions and spirits2) functioned3. These translations made 'learned' medicine available to those surgeons who didn't have a university education and couldn't read Latin fluently. "A grasp of the temperaments, humours, etc. enabled the surgeon to integrate physic with surgery, and allowed him when faced with a particular case to decide on a specific course of action."4

Sea surgeon John Woodall advised his readers

to read much, I mean in Chirurgery and Physick, and well to consider and beare in minde what he reads, that as he hath neede of the helpe of his bookes, he may againe find the thing he once read, which wil turn much to his profit: for otherwise what use hath a man of reading, if he forget it presently?5

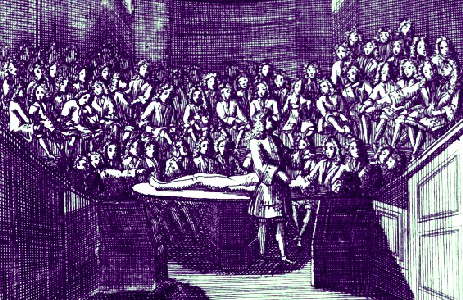

During the 17th century, there weren't university-based surgical programs available in England. "Surgery did not succeed in obtaining a structural place in the curriculum

French Surgeon Pierre Dionis Instructing,. From Cours d'Operations de Chirurgie (1708)

of the universities in northwestern Europe, where it was only occasionally tutored in special courses."6 Some of these surgical courses were added as Physicians became interested in surgery.7

However, it wasn't until the 18th century that qualified surgeons began earning university doctorates. As noted, training before this was provided by apprenticeship. A boy was apprenticed to a master surgeon for seven years to learn the trade. "[I]n theory at least he was required to be articled by his parents to the master’s guild, and might even obtain a licence to practice from the bishop of that diocese, as [sea surgeon James] Yonge did at Exeter."8 Even so, the entirety of Yonge's seven year training actually took place on ships.

In order to provided 'learned' counsel, the surgeons felt they had to be able to access the two techniques of 'learned' medicine outside of surgery: diet and medicine. These areas were regarded by the physicians as their province. Ware notes that "surgeons wanted to offer advice on diet and to prescribe medicines, as the physicians were doing."9 Medicine was a topic of particular importance, particularly

From De Efficaci Medicina Libri Tres,

By Marco Aurelio

Severino, Title Page (1646)

for sea surgeons, and references to prescriptions appropriate to various illnesses are found in their books.

Many surgical authors gave advice on diet. For example, Woodall makes recommendations about the patient's diet for his treatments of animal bites and stings10, wounds of the nerves11, wounds of the head12, apostemes (abscesses)13, amputation14, scurvy15, diarrhea16, iliac passion17, colic18 and callenture [a type of fever]19. When discussing the diet for amputation, he also goes into quite a bit of detail, advising his readers to "appoint him [the patient] a slender diet, namely no flesh: let him have a comfortable Caudle [a gruel of spices and wine] for the first, if you see him weak; and afterwards Broths and Pannadons [another gruel made with bread] and light things, and in small quantity."20

Of course, the surgeons' desire to add the 'learned' aspects of medicine to their regimes was about more than than just improving the prestige of surgery. As Ware explains, "there is no doubt that those who wanted to create a learned surgery believed that this was the way to improve the therapeutic results of surgery."21 Being able to recommend appropriate medicines and a proper diet were seen as ways to better serve their patients.

The surgeons also improved their standing simply improving their own methods. "[T]echnical improvements in surgery elevated the social standing of the profession. Physicians turned to surgery, and some surgeons turned to medicine."22

1 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, 1992, p. 218; 2 See Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, pp. 3 - 20 for a full explanation; 3 For examples, see Thomas Brugis, "To the Young Artist By way of Instituion", Vade mecum: or, A Companion For a Chirurgion", 1689, not paginated, James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiae, 1685, pp. 349 - 408 & Paré, pp. 3 - 40, among others; 4 Wear, p. 223; 5 John Woodall, "The Office and Duty of the Surgeons Mate", the surgions mate, 1639, 3rd page; 6 Iris Bruijn, Ship's Surgeons of the Dutch East India Company, 2009, p. 28; 7 Bruijn, p. 33; 7,8 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640 - 1714, 1958, p. 132; 9 Wear, p. 225; 10 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p, 132; 11 Woodall,1617, p, 133; 12 Woodall,1617, p, 137, 138 & 139; 13 Woodall,1617, p, 149-52; 14 Woodall,1617, p, 175; 15 Woodall,1617, p, 178,179, 183, 186 &189; 16 Woodall,1617, p, 209; 17 Woodall,1617, p, 240-1; 17 Woodall,1617, p, 248-9; 20 Woodall,1617, p, 175; 22 Bruijn, p. 47