Memento Mori: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Memento Mori in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Memento Mori Jewelry

Photo: Frank Kovalchek

A Modern Pirate Actor with Skull Jewelry

Modern portrayals of pirates often include skull and cross bone jewelry, seen on patches, hats, rings, buckles, buttons, pins and other paraphernalia. Such jewelry is designed to communicate the fact that the wearer is a pirate. Oddly, this is something no 17th or 18th century pirate would have wanted to do in public. (Piracy was a hanging offense, after all.)

The only place a pirate might want to advertise his trade was during the taking

John Paul Jones Pirate Caricature with Skull

Emblems,

British Engraving (19th century)

of a ship, but this was more readily done using the pirate's flag and cannons; actions spoke louder than jewelry ever could.

So it would appear that skull and bones jewelry is just another myth of pirate lore, albeit one with roots going back to the 19th century as seen in the British caricature at left.

Except memento mori jewelry actually did exist in the 17th and 18th centuries, apparently enjoying popularity among the general public. Mourning and memento mori jewelry has an interesting history that includes the entirety of the golden age of piracy. It looked a bit different than what is often seen on pirate costumes today, but skulls and crossed bones did occasionally figure into period jewelry, primarily as a reminder of death or a sign of mourning for a lost friend or loved-one. While memento mori symbols appeared on a variety of different types of jewelry, it is most widely associated with time pieces and rings.

Memento Mori Jewelry: History

Memento Mori Jewelry began appearing as early as the 16th century1,

Charles I Mourning Locket (late 17th c.)

although it didn't really gain widespread acceptance until the mid/late 17th century. Boston-based jeweler and collector Sarah Nehama explains that Memento Mori Jewelry became popular after the beheading of Charles I in 1649. "Royalists, distressed at the loss of their king, took part in a groundswell of public mourning that, albeit necessarily secretive, still led to the commissioning and wearing of rings, lockets, and other jewels on an unprecedented scale."2

This mourning jewelry also expressed loyalty to Charles II, Charles' I's son. When Charles II was crowned in 1660, the Royalists no longer had to hide their emblems under their clothes, so they began bringing memento mori jewelry into the open and thus into popular fashion.3

Mourning and memento mori jewelry took a variety of different forms. These included brooches, pendants, lockets, watches and rings. Nehama explains,

Memento Mori Hair Brooch Featuring Skeleton,

Hourglass and Staff or Dart. Behind the Skeleton

is Woven Hair From the Deceased (1689)

Skulls, skeletons and coffins, often worked in gold and enamel were the predominant motifs vividly illustrating the underlying sentiment of pending mortality. An important part of the memento mori jewelry was the use of text to express thoughts of death, mortality, remembrance and religion. Composed in Latin, French or English they were either engraved or enameled on the outside of a jewel or secretly on the inside, viewable only by the intended recipient.4

Jewelry historian Diana Scarisbrook agrees, explaining that the late 17th century saw "a demand for jewelry and rings decorated with hour-glasses, death's heads and coffins, inscribed in Latin or in English with admonitions such as PREPARE FOR DEATH; LIVE TO DIE; and KNOW THYSELF AND THOU WILL KNOW GOD."5

The fascination with memento mori jewelry continued and built in the early part of 18th century. Melbourne-based jewelry historian Lord Hayden Peters noted that "memento mori motifs [were] in popular format for mainstream jewelry and the industry had appropriated those motifs for death to a higher degree than the previous century."6 Nehama explains that by the end of the 17th century, Memento Mori Jewelry had caught the interest of the American colonies, where several "goldsmiths and jewelers had established their trade in Boston and other cities, including New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, as well as in surrounding towns."7

Coffin & Skeleton Pendant, Victoria & Albert Museum (1540 -50) |

Skeleton & Coffin Pendant Victoria& Albert Museum (1660) |

Memento Mori Skeleton and Coffin Pendant, Wellcome Museum, London (18th century) |

1 "The History of Mourning Jewelry, Remembrance Jewelry, Memento mori Jewelry and Cremation/Crematory Remains Jewelry", Ashesthouart.com, gathered 9/21/14; 2 Sarah Nehama, In Death Lamented: The tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, p. 16; 3 Nehama, p. 16-7; 4 Nehama, p. 22; 5 Diana Scarisbrook, Rings: Jewelry of Power, Love and Loyalty, p. 162; 6 Lord Hayden Peters, Spooky! Skeletal Rings, Memento Mori and the Evolution of the Symbol, artofmourning.com, gathered 9/20/14; 7 Nehama, p. 22

Memento Mori Jewelry: Time Pieces

Time pieces with a memento mori theme began to appear in the popular culture in the mid 17th century, although memento mori time pieces date back to at least the 16th century. The connection was an obvious one, with the watch's march of time suggesting that the owner's time on earth grew shorter with each passing tick.

This connection was even found on time pieces on the street. "Public clocks would be decorated with mottoes such as ultima forsan ('perhaps the last' [hour]) or vulnerant omnes, ultima necat ('they all wound, and the last kills')."1 Some of the automated Augsburg clocks even used the figure of Death to strike the hour.

Private citizens carried pocket watches encased in skulls as a reminder of their mortality. There are several examples of 17th and 18th century memento mori skull watches still today, although they are rare. (This is

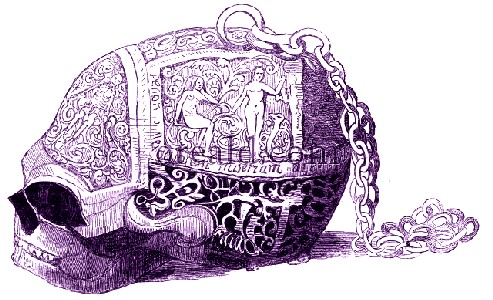

Mary Queen of Scots Skull Watch, Cassell's Illustrated History of England, Vol. 2 (1873)

probably because a typical silver pocket watch would have been worth about 3 months wages for an unskilled laborer.2)

The memento mori design enjoyed some popularity among watch buyers during this time; watchmakers in Switzerland, France, Germany and England all made watches which included skull designs.3

Perhaps the most famous of the skull pocket watches is the silver gilt one commissioned by Mary Queen of Scots shortly before her death in 1587. The back of the skull is ornately decorated, featuring figures of Death with his scythe and hourglass, Adam and Eve, and the Crucifixion. "The case is opened by dropping the under jaw, which turns upon a hinge, while the watchworks occupy the place of the brain. The lower part of the skull is pierced to emit the sound when it strikes... The works occupy the brain's position in the skull fitting into a silver bell which fills the entire hollow of the skull. The hours are struck on this bell by a small hammer on a separate train."4

Other skull pocket watches follow a similar design scheme, often featuring memento mori style designs such as the skull and bone and flower designs on the skull, seen on the 1744 watch below. Note the similarity in design between the 18th and 16th century watches.

Skull Pocket Watch, Verge Fusee Repeater by Joseph Martineau (1744) |

Verge Fusee Repeater Skull Watch Opened (1744) Verge Fusee Repeater Skull Watch Opened (1744)

|

1 "Memento mori", Wikipedia.com, gathered 9/21/14; 2 This number is based on wages from the mid-18th century, found in "The Cost of Living", The First Foot Guards", footguards.tripod.com, gathered 10/13/14; 3 Dahlia Jane, Memento Mori Watches, Upon a Midnight Dreary, uponamidnightdreary.com, gathered 10/13/14; 4 "Haunted Horology Week! Mary Queen of Scots Skull Watch", The Watchismo Times, watchismo.blogspot.com, gathered 10/13/14

Memento Mori Jewelry: Rings

Rings were the most common form of macabre jewelry. There were originally two types of rings related to death: the memento mori ring, a reminder to the wearer of their mortality; and the memorial or mourning ring, which a reminder to the wearer of someone they knew who was deceased. We have discussed the idea of memento mori art styles in some detail, so let's look at memorial rings.

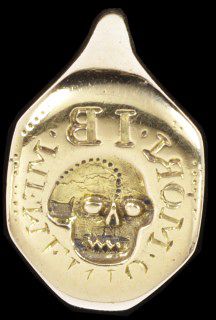

A Simple Memorial or Mourning Ring with a Death's Head on the

Outside and an Inscription on the Inside

- From the

Trustees

of the British Museum (1673)

Memorial rings were made and given out to friends and family following a death. The decedent's will specified money which was to be used to create mourning rings for a particular list of mourners. This practice began to gain in popularity in the 16th century, originally in the form of plain bands which were engraved with a references to the deceased on the ring.1

These rings were given out at the funeral "to clergymen, pallbearers, family and close friends, and other mourners.... [R]ings of varying quality [were sometimes] made, specifying the amount allotted for each type, with the more expensive items reserved for close family and socially prominent individuals."2 While such memorial rings could be worn on the finger, they were also hung around the neck or from ribbons at the wrist and arm.3

Memento Mori Ring Design by Pierre Woeiriot,

from Livre d'Aneaux d'Orfeverie (1561)

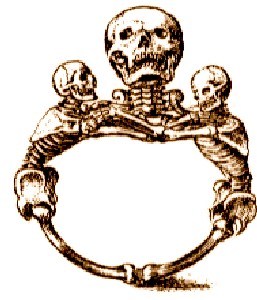

In the 17th century, memorial rings gradually merged with memento mori rings. The inscription, which might include dates, initials and other inscriptions, was moved from the outside of the ring to the interior, allowing memento mori symbols to be engraved on the outer surface.4 Such rings incorporated some of the same symbols seen in other memento mori art forms including skeletons, skulls, wings, coffins, laurels, grave digger tools (such as spades and picks5) and hourglasses.

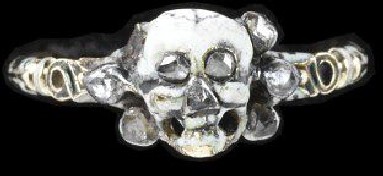

Memento mori symbols also began to appear on ring signets, which were engraved with a death's head or a skeleton holding the symbols of dart and hourglass. [See the example below left.] The skull was not always centered in the bezel; sometimes it appeared on the shoulders, resting on crossbones.6 Rings might also incorporate engraved gems, with emblems such as "skeletons, skulls, butterflies representing the souls of the dead to Charon who will ferry them across the Styx, and philosophers either meditating alone or lecturing on the mystery of life and death."7

Memento Mori Signet Ring,

From

the

Victoria and Albert Museum,

London (17th c.)

By the end of the 17th century, memento mori/memorial rings had become an industry.8 Such rings were made by jewelers specializing in this style of jewelry, who usually focused on the popular mournings rings. Jewelry historian Diana Scarisbrick explains that while such rings were not all the same in the late 17th century9. By the early/mid 18th century,

Designs [of memento mori/mourning rings] usually conform to a standard pattern. The bezel is set with either a slab of crystal or a coloured gem, with or without [the decedent's] hair below, supported on a hoop subdivided into five scrolls, inscribed with the name and date of death, [with the ring being] enameled white for the unmarried and black for the married.10

The distribution of memorial items at funerals became so widespread that socially prominent individuals were able to collect a great many of them. In his personal diary of events from 1674-1729 puritan judge Samuel Sewall of Massachusetts mentions "hundreds of burials he attended over some five decades and notes dozens of mourning rings he received, as well as other gifts such as gloves and scarves."11 In fact, the custom become so widespread, that in 1741 the Massachusetts provincial government outlawed the giving of mourning rings, 'upon penalty of 50 pounds.'"12

Below are a couple other samples of rings featuring memento mori symbols from the golden age of piracy.

Black Enamelled Skeleton Mourning Ring , From the Trustees of the British Museum (1679) |

Second Black Enamelled Skeleton Mourning Ring, From Second Black Enamelled Skeleton Mourning Ring, From the Trustees of the British Museum (1714) |

Memento Mori Skull and Bones Ring, From the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (1680 - 1720) |

Skeletons Holding Coffin Container Mourning Ring, Skeletons Holding Coffin Container Mourning Ring, From the Trustees of the British Museum (17th c.) |

1 "Memento Mori", langantiuques.com, gathered 9/21/14; 2 Sarah Nehama, In Death Lamented: The tradition of Anglo-American Mourning Jewelry, p. 16; 3 Diana Scarisbrick, Rings: Jewelry of Power, Love and Loyalty, p. 166; 4 Nehama, p. 16; 5 Margriet Sopers, "Memento Mori and Mourning jewelry", February 29, 2012, gathered 9/21/14; 6 Scarisbrick, p. 166; 7 Scarisbrick, p. 161-2; 8 Nehama, p. 16; 9 Scarisbrick, p. 170; 10 Scarisbrick, p. 172; 11 Nehama, p. 23; 12 "Death Parts United Hearts", The Recovering Protestant, gathered 10/14/14

Memento Mori Jewelry: Did Pirates Wear Them?

Having seen some of the jewelry that was around during the golden age of the pirates in Europe and the American Colonies, a natural question might be, "Wouldn't pirates have worn such things?"

The answer is somewhat complex, lying in the nature of the pirate

.jpg)

Artist: Howard Pyle -

So the Treasure Was Divided (1905)

community. Many pirate groups were organized around a set of rules called articles (sometimes erroneously referred to as 'Pirates Code' thanks to a certain movie.) These articles spelled the rules of the group, including each man's share of what was taken off a prize.

Typically each man got one share with some of the officers getting extra shares. For example, the captains and quartermasters in Bartholomew Roberts' fleet each received two shares while the Masters, Boatswains and Gunners got 1-1/2 shares and the rest of the officers got a share and a quarter.1 Other crews divided their take somewhat differently, but the idea that the officers received slightly more than the rest of the men was normal.

At the same time, the pirate's articles also detailed the punishment that would be doled out to anyone caught stealing from the communal chest before the spoils were divided among the crew. In Captain John Phillip's articles, Article 3 states, "If any Man shall steal any Thing in the Company, or

game [gamble], to the Value of a Piece of Eight, he shall be marroon'd

or shot."2

Artist: Howard Pyle

Some Things Are Not Easily Forgiven,

Colonel Rhett and the Pirate (1901)

So even if a man were inclined to carry off a piece of jewelry that caught his fancy, he wouldn't be likely to actually wear it and risk being shot or marooned.

The rules applied to everyone; even the captain could get into trouble borrowing from the community prizes. After taking William Snelgrave's slave ship, pirate Captains Levasseur, Cocklyn and Davis decided to 'borrow' some of Snelgrave's coats which had been captured so that they could go into town and look good for the local women. The crew was not pleased.

"The Pirate Captains having taken these Cloaths without leave [permission] from the Quarter-master, it gave great offence to all the Crew; who alledg'd, 'If they suffered such things, the Captains would for the future assume a Power, to take whatever they liked for themselves.' So upon their returning on board next Morning, the Coats were taken from them, and put into the common Chest, to be sold at the Mast."3

This means the only way a pirate might end up with a piece of Memento Mori Jewelry was if the crew had agreed to give it to him. Sometimes extra gifts were awarded to the first man to spot a ship that produced plunder or to the men who actually boarded a ship, but the items that we know about only include guns and clothing4, not jewelry.

A pirate might also end up with such jewelry as part of his share of the prize money, but it seems doubtful that most pirates would keep such jewelry rather than sell it. The money a piece of jewelry would fetch could be used to purchase alcohol and women, which would be far more appealing than something that would be difficult to explain if a pirate were caught with it. So it is unlikely that a pirate stole and wore or kept Memento Mori Jewelry purely for aesthetic purposes.

1 Captain Charles Johnson, A general history of the pirates, 3rd Edition, p. 232; 2 Johnson, general history, 3rd Edition, p. 398; 3 Captain William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave Trade, p. 257; 4 Johnson, general history, 3rd Edition, p. 230