Fractures Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

Fracture Treatment During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Types of Fractures

When considering the best way to cure fractures, period surgeons divided them into two types: simple and compound. Compound fractures are those with a wound; simple fractures are those without. This division hearkens back to the works of Hippocrates, whose works were still in print and being used for training young surgeons and physicians.

Artist: Wiki User Saltanat

A Rather Grisly Compound Fracture of the Lower Leg

Hippocrates suggested that simple fractures were easy to cure. "There is no necessity for much study, then, in order to set a broken arm, and in a word, any ordinary physician can perform it"1.

Sea surgeon John Moyle gives a basic outline for the cure. "For if it were a Simple Fracture, having no Wound with it in the Flesh, then it were but only extending of it, and reducing the bones [putting them back into proper alignment], and applying the defensive [medicines] and apparel [bandages], and so the work were done."2

Compound fractures were a bit more complicated because of the wound that accompanied them. Sea surgeon John Atkins suggests there are actually two different types of compound fractures, noting that the term "may signify a double Fracture of the same Bone, or when the Accidents of Inflammation, Erysipelas [infection of the skin], and consequent Apostemation [discharge of pus], has succeeded to a simple Fracture; but Custom has confined the Appellation strictly to such Fractures as are immediate accompanied with a Wound, whether the Bone appear through such Wound, or not."3 Atkins goes on to glibly suggest that compound fractures were just simple fractures with "the additional and indisputable Evidence of Sight [to prove that a fracture existed]."4

The wound created an additional step in healing, mostly consisting of the application of medicines and appropriate bandaging which will be discussed in greater detail later.

1 Hippocrates, Hippocratic Writings, Translated and Edited by Francis Adams, p. 74; 2 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 115-6; 3,4 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 63

Detecting a Broken Bone

Before anything else could be done, the surgeon had to verify that the patient actually had a fracture. Today this is done with X-ray machines, which provide indisputable proof of fracture in most cases. X-ray machines came about almost 200 years after the golden age of piracy, however. Broken bones had to be detected by direct observation at this time. As John Atkins hinted in the previous section, this could more easily be done when the fracture was compound; the wound provided the surgeon visual entry into the body. It was not so easy with a simple fracture.

Ambroise Paré explains that the best way to detect a fracture is "by handling the part which we suspect to be broken, [where] wee feele peeces of the bone severed asunder, and heare a certaine crackling of these peeces under our hands, caused by the attrition [wearing away] of the shattered bones."1 Richard Wiseman similarly notes that when

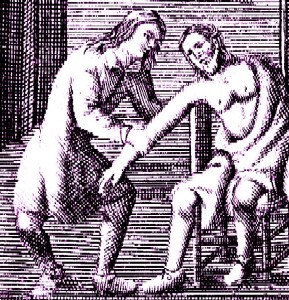

From Medicinesche Chirurgische und Anatomische

Schrifften

by Paul Barbarette

(1692)

"you handle the fractured Member, you shall perceive a crashing of Bones"2 further explaining that you could "feel the pieces of Bones severed asunder, and hear them crackle."3 John Atkins advises that the surgeon can "feel the Ends of the Bone to crush and pass by one another, without Stability to resist any Motion which is made with it; and of this, unless we have lost our Feeling, we can hardly be deceived"4.

Paré goes on to detail what he considers the second best method for detecting a simple fracture. "Another signe is taken from the impotencies of the part, which chiefly betrayes its selfe"5. Richard Wiseman expands upon this 'impotency,' explaining that it is such "that the Patient cannon lean upon it."6 Atkins advises the surgeon that he will note an "Inaptitude of the Limb to move itself, which will immediately succeed a Solution of Unity [follow a breakage]."7 Atkins warns his readers that "it is an Error of those who expect the Parts distant [from the fracture] should be under the same Incapacity; such I mean, as moving the Toes on a Fracture of the Leg or Thigh, or the Fingers in that of the Arm or Cubit; for let those Bones be never so shattered, it will not destroy the Motion of these, because they imply no Disturbance to the Fracture; which, though it affects all the Joints above, does only deprive the next below it."8

Artist: Gerritt Lunders

From The Surgeon (1649)

Pain is considered another reliable indicator by some period authors. Wiseman considers it fourth among the seven signs his lists for detecting a broken bone. "There will be extraordinary Pain, in regard of the divulsion [tearing apart] of the Nerves, and distortion of the Tendonous bodies; also a pricking in the Fleshy parts by the sharp ends or Shivers [slivers] of some Bone."9 The idea that the bone break causes distortion and pricking is noted by Paré. "Greate paine in the interim torments the patient by reason of the wronged periostium [a tough membrane attached to the bone], and that membrane which involves the marrow and the sympathie of the adjacent parts which are compressed or pricked."10 Atkins dissents, believing that while pain does accompany a fracture, it isn't enough by itself to indicate a fracture.11

Wiseman suggests a couple other methods for detecting fractures. Similar to handling and finding the bones to move beneath the skin, he suggests that the surgeon "shall perceive a Cavity, if you touch the Parts above and under the Fracture."12 He also advises, "Hippocrates bids us compare the sound Parts [non-fractured limb] with the Parts affected, and observe the inequality."13 Wiseman later explains "the fractured [member will be] the shorter [of the two]."14 His seventh suggestion for detecting fracture is that "The asperity [abrasiveness] and inequality or roughness of the Bone [will] manifest it [the fracture] to you: but the search will give you no small assurance."15

Atkins dismisses all of these as reliable indicators, explaining that neither "Tumor, Distortion, Shortness of the Limb, or any Disparity with the sound one [limb], (though reckoned Symptoms of a Fractures, ) are sufficient indications of themselves because they all severally do happen to the Limbs on other Accidents, and, in their Turns, may be separate Distempers of them."16 He has a point.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p.162; 2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 419; 3 Wiseman, p. 465; 4 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 40; 5 Paré, p.162; 6 Wiseman, p. 419; 7,8 Atkins, p. 40; 9 Wiseman, ibid.; `0 Paré, p.162-3; 11 Atkins, p. 40-1; 12, 13 Wiseman, ibid.;14 Wiseman, p. 465; 16 Atkins, p. 40-1

Fracture Repair Theory

Period surgeons suggested a number of steps to follow in their theory of healing broken bones during the golden age of piracy. French surgeon Ambroise Paré proposed three steps that the surgeon must perform to cure a broken bone:

French Surgeon and Author Ambroise Paré

The first is, to restore the bone to its place:

The second is, that he containe or stay it being so restored:

The third is, that he hinder the increase of maligne symptomes and accidents; or else if they doe happen, that then he temper and correct their present malignitie. Such accidents are paine, inflammation, a feaver, abscesse, gangrene and sphacell [death of the part].1

Sea surgeon John Woodall basically recommends the same three steps, possibly having read them in Paré's book. In addition to restoring the bone, he suggests "taking away any loose peeces or fragments of bones if any be."2 Woodall also notes that the third step should include "the curing of the wounds or contusions incident to fractured bones."3

Although he does not list them ordinally, German military surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann recognized the same basic principles. He specifies that containing the fracture (Paré's second step) should be performed by "keeping them [the bones] so [in their proper place] by good Bandages... [and] laying the part in an easy place and a regular Posture"4.

Military surgeon Richard Wiseman also agrees with the Paré's three steps, although he adds two more. His first two steps were setting the bone and making sure it stayed in place and his last step is the same as Paré's third step to prevent accidents. However, he inserts two steps in between securing the bone and correcting accidents. "Thirdly, to preserve the Tone of the Part; Fourthly, to generate Callus"5. These are both useful additions to the theory of repairing broken bones, but they require an explanation.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p.167; 2,3 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 60; 4 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 213;

5 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 465

Fracture Repair Theory: Preserving Tone

Period Medicines - A Part of "Preserving Tone"

Wiseman's third step in repairing fractures is preserving the tone of the part. When we hear "tone" of the body today, we often think of maintaining musculature through physical therapy. This is a relatively modern concept, however. Richard Wiseman is referring to something very different. As he explains in his book, "Natura enim os unire nequit, nisi pars sit sana; Nature cannot knit the Bones while the Parts are under a Distemper"1.

So he is actually referring to ways to heal the wound in compound fractures or the space created inside the body by the broken bone in simple fractures. As Wiseman reveals, "though fractured Bones be very well set, yet there will remain some Cavernulæ [small space], which will be apt to fill with Sanies [serum, blood and/or pus], which the Part through its weakness can neither well assimilate nor expel, and so is like to be burthened with excrementitious Humours."2 The way to remove such problems is through the use of medicines, bleeding and similar methods. This is actually the same thing that John Woodall wanted to add to Paré's third step.

1,2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 469

Fracture Repair Theory: Generating Callus

Richard Wiseman's fourth step is to generate a callus. Callus is the material the forms around or between breaks in the bone. It is initially soft like cartilage, but it gradually converts into bone. Paré notes that it is a "hard substance ...which glues together the fragments thereof, being fitly put together."1 Sea surgeon John Atkins says callus "is a white thick viscous Substance... dispersed through the Substance of the Bone, and is a Juice, that by its being so continually at Hand in Fractures, has probably a constant Circulation through the Bones"2.

Although rather rudimentary in their understanding of how bones are repaired, the period authors were on the right track. When a bone is broken, blood clots form around the break, bringing in white blood cells which remove dead or

Photo: Wiki User SubtleGuest

Bone Construction Assisting Fibroblasts in a Mouse Embryo

dying material from the wound. At the same time, blood clots bring fibroblast cells to the wound site which produce connective collagen fibers. The blood clot is gradually replaced by collagen. The fibroblasts then begin to create a bone matrix into which bone crystals are deposited, strengthening the collagen. This is eventually replaced by a micro-structure of bone.3

The amount of bone that can be regenerated is also discussed by period authors. John Atkins makes some rather extraordinary claims, suggesting that when "a great deal of the Substance of the Bone lost, we are apprehensive that so large an Interval or Space can never fill up with Callus to support the Actions of that Limb"4. However, Atkins explains that he has personally seen regeneration occur when the loss of bone is "above two Inches; but [I] have heard Relations, and seen Instances of greater, particularly at our [Surgeon's] Hall; where a greater Focile [tibia] of the Leg was shewn, from which had been taken away, of the Substance of the Bone, to the Length of five Inches, and that intermedial Space supplied with strong Callus."5

Atkins gives details of the 2 inches of missing bone case he tended.

After having cleared the Wound of Extranea, I found the Ends of the Bone near two Inches asunder: A Distance that surprized me not a little; but having known as large a Void to fill with Callus, I resolved to wait the Event of Nature in it, and preserve the Limb if possible. The Bone I dressed with Tinct. Myrrh. [used to prevent infection] the Wound with Digestive [to cause supperation], and the Fracture with the same Compresses and Bandage as above, taking particular Care in the Situation of it, that the Ends of the Bone pointed to each other, and that the Whole lay smooth.6

It is possible that Atkins is referring to a particular type of fracture known today as a comminuted fracture - one where the bone has broken into mutiple pieces, although his description doesn't hint at this.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 64; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 50; 3 Adapted from "Pathophysiology," Bone fracture, wikipedia, gathered 3/9/14; 4,5 Atkins, p. 63; 6 Atkins, p. 69-70

Fracture Repair Theory: The Four Steps

Author Richard Wiseman

Since Richard Wiseman has given the most complete framework for understanding how fractures are cured, we are going to combine two of his five steps, and slightly restate his original comments to create four steps to repair a fracture during the period:

Step 1: Restore the Bone

Step 2: Maintain the Bone's Position to Generate Callus

Step 3: Preserve Tone

Step 4: Prevent Accidents

Much of the remainder of this document will focus on these steps, looking at each in detail. Before moving on, however, there are a couple of other elements period surgeons and physicians considered in the theory of treating fractures that should be mentioned.