Fluxes/Diarrhea and Related Illnesses Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Next>>

Treating Fluxes in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 7

Treatment of a Flux: Internal Medicines

The vast majority of the prescribed cures of a flux were medicinal. Our period medical authors prescribe a wide variety of medicines for fluxes. As sea surgeon John Woodall explains, "there are innumerable sorts of remedies which wee must so compound [mix], that they may have one similitude [resemblance], or one Analogy [to] the disease"1. Because of the number and variety of medicinal cures, we will spend the next several pages looking at the various types of medicines, examining some of the repeated and familiar cures in detail.

Woodes Rogers and his Men, from A

Universal Collection of Authentic and

Entertaining Voyages and Travels,

p. 86 opp. (1765)

Although Woodall and other period sea surgeons spend a lot of time discussing medicines, surgeons were not usually involved in diagnosing illnesses and prescribing medicines. Prescribing was the purview of physicians. Preparation of prescriptions was handled by the apothecaries. At sea, however, there were usually no physicians on a ship (particularly on a pirate ship.) Even less frequent at sea was the apothecary since his art involved working with things that were found almost entirely on land.

A rather notable exception to this was Woodes Rogers' privateering voyage that took place from 1708 to 1711. That had both a physician and an apothecary. The physician was Dr. Thomas Dover who, despite having a thriving trade as a physician, financed the voyage and insisted upon going. In addition, "Samuel Hopkins, being Dr. Dover's Kinsman and an Apothecary, was both an Assistant to him, and to act as his Lieutenant, if we landed a Party any where under his Command during the Voyage"2. However on most journeys, it was up to the surgeon to prescribe, prepare and administer medicines.

Like today, there were medicines with many different properties which physicians grouped by type. Naval physician Thomas Aubrey explains in his cure for diarrhea, that the physician is to "[b]egin with the general Evacuations, then administer Emulsions, Cardiacks, Diaphoreticks, and Anodynes, as you will see"3. Unlike today, terminology was quite fluid and we find many different terms for medicines that served the same purpose. For example, what Aubrey calls cardiacks, other authors call cordials.

Fortunately, there were two English language Pharmacopeias printed around this time, which agree in many respects on the terminology: John Pechey's The Complete Herbal of Physical Plants, printed in 1694 and Nicolas

Author Nicholas Culpeper

Culpeper's Pharmacopœia Londinesis, the version of which I have was printed in 1720. (It was first printed in 1649 and has been in print in one form or another ever since.) Using these two books where they help and two other post-period pharmacopeias, I have divided the medicines into a couple of categories to make the large number of medicines a bit easier to comprehend.

It should be noted that several medicines had multiple properties and could fit easily into more than one category. Where the pharmacopeia authors have listed the different properties of a medicine in order of importance, I have used that as a guide in placing them into a particular category. Where they have not, I focused here upon the quality of a treatment that would appear most useful in a flux. Any errors in placing a medicine into a particular category are entirely mine, however.

With these caveats in mind, let's look at the medicines for fluxes, divided into Alexipharmics (antidotes), Anodynes (pain killers), Astringents (drying medicines), Cathartics (medicines to increase defecation), Cordials (soothing/warming and stimulating medicines), Diaphoretics (sweat Inducing medicines) and Emetics (purging medicines). We'll also examine William Cockburn's Electuary (a medicinal paste), because it had an important impact on sea medicine for fluxes. Lastly we'll discuss some unusual prescriptions, some of which you may find amusing, if not horrifying.

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 207-8; 2 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, p. 7; 3 Thomas Aubrey, The Sea-Surgeon or the Guinea Man’s Vadé Mecum, p. 77

Treatment of a Flux: Internal Medicines - Alexipharmics (Antidotes)

Photo: Linda Tanner

"Now don't go blaming me for your running bowels, sir!"

(My expert editress tells me that this is a corn snake, which is

not at all venemous. Yet he looks like a velociraptor.)

Alexipharmics seem like an unusual remedy to give to someone with a flux. The Freedictionary defines alexipharmic as being "a remedy for or antidote against poison or infection."1 Based on that definition, it may be that alexipharmics were included to help resist an infection the doctor suspected was causing the flux. Sea surgeon John Woodall, while debating whether to bleed or not, explains that when dysentery "proceedes from contagious and venomous aire, and is fierce, I holed it the safest course to for beare bleeding or purging, for feare of drawing backe the venome to the principall parts, and rather to flie to Alexipharmacons or Preservatives, as Venice Treakell, Mithridate, Diatesseron, London Treakell, or the like"2.

Alexipharmics may also have been used because period physicians felt that such prescriptions had other properties which were useful to a medicinal concoction. As you will see when we discuss treacles, those were reputed to be useful in many different cases.

It could also be as simple as the surgeon or physician finding an ingredient had worked elsewhere and thought that it might work here. As you will quickly discover, sea surgeon John Woodall and military surgeon Raymund Minderer put anything and everything in their medicinal suggestions for curing a flux.

Treatment of a Flux: Internal Medicines - Alexipharmics -- Treacle

When period medical authors speak of treacle, they are not referring to the syrup that many people think of when they hear the term today. They are referring to complex herbal concoctions often containing dozens of ingredients that were thought to be antidotal for venomous bites.3 In fact, the term 'Treacle' is used almost interchangeably in period documents with the word from which it appears to have been derived: theriac.

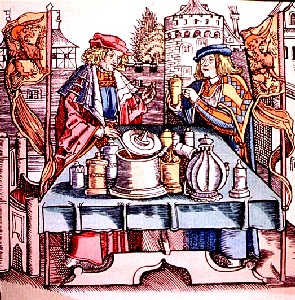

Apothecaries making Theriac in Stuttgart, middle ages

Two primary kinds of treacle were prescribed during this period for fluxes: London Treacle and Venice Treacle. The ingredients were quite different. Of the London Treacle, Culpeper says it "resists poyson, strengthens cold stomachs, helps digestion, [and] crudities of the stomach."4 He gives the Venice Treacle an even more impressive reputation explaining that it

resists poyson, and the bitings of venemous Beasts, inveterate Headach, Vertigo, Deafness, the Falling sickness [epilepsy], Astonishment, Apoplexies, dulness of sight, and want of voice, Asthmaes, old and new Coughs, such as spit or vomit blood, such as can hardly spit or breathe coldness of the stomach, wind, the Cholick and Iliack passions, the yellow Jaundice, hardness of the Spleen, Stone in the Reins and Bladder [kidney stones], difficulty of Urine, Ulcers in the Bladders, Fevers, Dropsies [Edema], Leprosies, it provokes the Terms [menstruation], it brings forth Birth and after-birth, helps pains in the Joynts, it helps not only the Body, but the mind, as vain fears Melancholy, &c and is a good remedy in Pestilential Fevers5

And I'll bet you thought penicillin was an amazing drug!

Photo: Jebulon

Theriac Apothecary Jar in

Pharmacie des Hospices,

Beaune, France

Why a poison remedy would be useful for 'crudities of the stomach' and similar problems, Culpeper doesn't reveal. However, based on his recommendations, you can begin to see why these 'poison remedies' might have been prescribed for fluxes.

Even so, our period surgeons are not always overwhelming in their prescription of theriac. Military surgeon Raymund Minderer gives a tepid prescription for such in cases of flux, telling the surgeon to "give the Patient now and then a little new-made Treacle, or mix with it a few grains of the Confection of Archigenes; for of such Medicamants a Field-Apotheque is not wont to be destitute."6

Sea surgeon John Woodall goes back and forth. For example, he suggested bleeding to be preferable to medicines such as treacles in the previous quote. However, he also suggests giving iron oxide (Crocus Martis - which we'll discuss in a later section) "with Venice Treakell, or London Treakell, or good Mithradate"7. For diarrhea, he explains that "Theriaca andromachi [Venice Treacle], or Theriaca Londini [London Treacle]{half dram} is very good given him upon the point of a knife"8.

1 Alexipharmic, thefreedictionary.com, gathered 3/9/13; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 211; 3 Treacle - Etymology, wikipedia, gathered 3/10/13; 4 Nicholas Culpeper, Pharmacopœia Londinesis, p. 167; 5 Culpeper, p. 166-7; 6 Raymund Minderer, A Body of Military Medicines Experimented, Volume 4 of Paul Barbette's, Thesaurus Chirurgiæ, The Fourth Edition, p. 74; 7 Woodall, p. 213; 8 Woodall, p. 203

Treatment of a Flux: Internal Medicines - Anodynes (Pain-Killers)

"Such Oyles, Ointments, and Plaisters, as ease pain, are called by Physitians (because you should not know what they mean) Anodines." (Nicholas Culpeper, Pharmacopœia Londinesis, p. 204)

An Apothecary at Work from The

Workes of That Famous Chirurgeon

Ambrose Parey, p. 418 (1649)

Anodynes - or pain killers - are another unusual medicine used for treating fluxes. Nicholas Culpeper continues his witty railing against name-dropping writers while explaining that Anodynes are divided into 'proper' and 'improper' medicines. He tells us the 'improper' medicines were translated out of Galen's writings as 'Narcotick', "for I assure you if crabbed words would would cure diseases, our Physitians would come behind none in the world"1.

Sea surgeon John Moyle explains why Anodynes are proper in relieving a flux.

This disease is not without tormenting and vehement pain, therefore you must (when requisite) apply Anodine means, yet such as may have both a Cordial and Astringent quality in them; yea, and that may strengthen the Spirits, and oppose Malignity withal. As,

Rx. Diascord[ium] {1 dram}, Diacoral[lorum - antimony and iron oxide] {half dram} Cons[erve] De Hyacinth. {1 scruple}, misce s. Bolus [mix into a bolus].

This taken is excellent (and especially if there be any thing of a Fever with the Flux) for it cools moderately, strengthens much, binds and stops the Flux powerfully, resists Malignity effectually, and seldom fails to give present ease and rest. It ought to be given at Night last, and Morning first.2

Mandrake Roots

Now you may be wondering what was anodyne about Moyle's prescription. It takes a bit of digging to find out. Diascordium is "a powerful astringent electuary containing opium and having a kaolin-like action through the presence in it of Lemnian sealed earth [or terra sigillata]."3

Kaolin, or china clay, is used in modern medicines to get them through the digestive system so that they do not begin to act until they arrive in the intestines. This, combined with the narcotic opium, explains the anodyne function of Moyle's medicine. It also reveals to us that narcotics were the primary type of anodyne medicines that were used on a flux.

Narcotics, particularly opium and medicines containing it, have wide support for treating fluxes among the period surgeons and physicians. Woodall recommends them, stating that "we must in extreame Disentery for the last remedy indevour to mitigate the pain with narcoticall things, as is the Oleum Insquiami mandragoræ [mandrake oil – the mandrake root contains hallucinogens], the cold seede, the Philonium requies Nicolai [a compounded medicine containing opium], and many other such like compositions which are unto this disease used"4.

Treatment of a Flux: Internal Medicines - Anodynes -- Opium

Photographer: Odedr,

Opium Poppy Seeds

John Pechey noted that opium seed were "used

to stop Spitting of Blood, the Bloody-Flux, the Flux of the Courses, and Hermorrhoids; for the Cholick, for hot Defluxions of the Eyes, and to quiet all Griping Pains."5 Based on his description, opiates would be considered highly appropriate in treating dysentery.

Physician William Cockburn explained that opium was not to be given directly but was to be mixed with "purging and binding Medicines, to strengthen and ascertain their Operation."6 The details of emetics (purges) and astringents (binding medicines) will each be discussed in their place; the important point to be taken from his comment is that opiates were not usually given alone. In fact, concoctions containing opiates such as Laudanum and Philonium were the most popular anodyne medicine prescribed in fluxes at this time.

Photo: Jolly Janner, Red Opium Poppy

Cockburn says that "the most sensible Effect of Opium is its laying Men quiet, and rendring them insensible, or very little sensible, of Pain...

From this its quieting Faculty it follows, that a Diarrhœa, caused by stimulating the Guts, may be cured by Opium, and opiate Medicines. For as we are quieted, by Supposition, with Opium, or that we are rendered insensible of the Stimulus by opiate Medicines, the stimulating Causes work themselves off while our Intestins are not irritated with the Stimulus."7

However, he goes on to say that "Opium does nothing of it self in the curing a Serous, or watry Loosness, and consequently its strengthning [of the stomach] and diaphotetick [sweat-causing] Power is indiscernable, and next to nothing."8 Cockburn is trying to explain why opiates work in some cases and not in others based on his theories about root causes of diarrhea. You will recall that he believed that there was a difference between diarrheas which contained chyle and those that didn't and that lack of sweating was a particular problem in a diarrhea.

Treatment of a Flux: Internal Medicines - Anodynes -- Laudanum

"...Laudanum in all Fluxes judiciously administred is the only sure helpe..." (John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 203)

The most frequently mentioned opiate for this illness is Laudanum. This was a liquid composed of various ingredients including opium. Esteemed London physician Thomas Sydenham gave his recipe as:

Photographer: Danny S

Laudanum - Opium Tinctura Take of Spanish Wine, one Pint; of Opium, two Ounces; of Saffron one Ounce; of the Powder of Cinnamon and Cloves, each one Dram: let them be infus'd together in a Bath two or three Days, till the Liquor comes to a due Consistence; strain it, and keep it for use.I do not think this Preparation has more Virtue than the solid Laudanum of the Shops; but I prefer it before that for its more commodious Form, and by reason of the Wine, or into any distill'd Water, or into any other Liquor.9

Military surgeon Raymund Minderer recommended it, stating that "when the pain is very great, you may then add to it [plantain juice or rice broath] some opiat Medicine, as of Trochisques de Garabe, or one only grain of Laudanum Opiatum."10

However, it is sea surgeon John Woodall who waxes eloquent about the use of

Photo: Den Haag

A Sliced Opium Poppy Bulb

Laudanum in fluxes. Building upon the quote that leads this section, he advises that "a dose of Laudanum opiat, is best to finish the worke for that goeth before, are rather exceedeth all other medicines in fluxes, for that swageth all paines and causeth quiet sleep, which often even alone is the true perfection of the cure."11

He first recommends it in the cure of diarrhea. He starts this particular prescription with a purge, followed by covering the patient to keep him warm. After that "you may give him within three houres three of foure graines of Laudanum, and let him againe incline himselfe to rest and by Gods helpe he shall be cured: but if he have a fevor give him an opiate first, I meane the Laudanum."12

He also suggests it for Dysentery, as mentioned in a special section he wrote on Laudanum. Woodall explains that no opiate medicine has "more shewed their admirable vertues, then that noble medicine called Laudanum Opiat Paracelsi [a recipe for Laudanum found in the works of Paracelsus] hath done in the cure of that lamentable disease called Dissenterie, or the bloody fluxe, as witnesseth divers of our nation coming from the East Indies upon good proofe, as also being no lesse approved of, not onely by auncient and moderne writers, but by every expert Surgeon comming from those countries out of their owne, too many experience thereof have bin made."13

His prescription for dysentery is to start with "one dose [of Laudanum]: you may begin in weake bodies first with opiate medicine in that there is most need of ease... if that answer not thy desire, thou

Apothecary Jars and Mortars

mayst returne to Laudanum againe and againe, alwayes remembring, as is sayd, there be foure houres at

the least distance, betwixt each dose"14. He later suggests that the dose be "three or foure graines of Laudanum Paracelsi, then after there may bee given him one scruple of the best Treakle or Mithridate, or London Treakle, or meerely Laudanum alone."15

Still, Woodall did understand that opiates could be dangerous to the patient if not properly handled. He warned that they "may not be administred except great judgement and advise had thereon."16 There is a hint of this in Thomas Sydenham's comments on the topic when Sydenham explains that "he that rightly understands it, will do greater things than can be well hop'd for from one Medicine"17.

However, Sydenham's primary point is that the medicine was good for more than just a practitioner "who only knows how to use it to promote Sleep, to ease Pain, and to stop a Looseness; whereas it may be accomodated, like the Delphick Sword, to many other uses: and it is really a most excellent Cordial Remedy. I had almost said the only one, which has been hitherto found amongst the Things of Nature."18

Of course, Sydenham's had a specific he was trying to sell. As he explained, "indeed I never perceiv'd the least Injury from so frequent a Repetition of the Narcotick Medicine"19.

1 Nicholas Culpeper, Pharmacopœia Londinesis, p. 204; 2 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 176-7; 3 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, p. 290; 4 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 208; 5 John Pechey, The Compleat Herbal of Physical Plants, p. 310-1; 8 William Cockburn, The Nature and Cure of Fluxes, p. 132; 9 Thomas Sydenham, The Whole Works of that Excellent Practical Physician Dr. Thomas Sydenham, 10th Edition, p. 123; 10 Raymund Minderer, A Body of Military Medicines Experimented, Volume 4 of Paul Barbette's, Thesaurus Chirurgiæ, The Fourth Edition, p. 74; 11 Woodall, p. 209; 12 Woodall, p. 204-5; 13 Woodall, p. 224; 14 Woodall, p. 208-9; 15 Woodall, p. 211; 16 Woodall, p. 208; 17 Sydenham, p. 123; 18 Sydenham, p. 123-4; 19 Sydenham, p. 122