Eye Wounds and Surgery Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 <<First

Eye Wounds and Surgery During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Pirate Eye Patch History

from wikimedia

If you look up 'pirate' on Google Image Search, you will most likely wind up with several cartoons and images of scruffy men wearing eye patches (in the midst of all those photos of Johnny Depp, of course.)

Like the arm hook and the peg leg (both of which I discuss on this web page), the eye patch has become emblematic of the pirate in our society. Yet, as I mentioned at the end of the previous page, we have no period accounts of pirates or even regular sailors wearing them. How did this come to be?

Pirate Eye Patch History - Pirates Missing Eyes

Although we don't have a record of a golden age of piracy period pirate or sailor with an eye patch, it is

"Edward Low Forces a Captive to Drink" featuring a

pirate with an Eye Patch. From The Pirates Own Book by

Charles Ellms

(1837). This image is completely inaccurate,

reflecting the time period it was drawn rather than the time it is

supposed to represent. In addition, no pirate missing an eye

was

ever

mentioned as being a part of Low's crew.

possible and even likely that anyone missing an eye would have worn one if they were at all concerned about their

appearance. (As was mentioned on the previous page, the function of the eye patch was almost entirely aesthetic. Don't believe any of that stuff about pirates using them to pre-adjust their eyes to darkness. It may or may not work, but if it were common, there would surely be some evidence in the extensive period literature and artwork. So far no one's found any such thing.)

Loss of an eye was clearly a concern for privateers, however. (Privateers were ships that had a Letter of the Marque giving them permission to take ships of nations who were enemies to the nation issuing the Letter on their behalf.) Alexandre Exquemelin's account explains that the English privateers paid for the loss of "an eye, 100 [pieces of eight] or one slave, and the same award was made for the loss of a finger."1 Pere Labat gives us similar information for French corsairs in the Caribbean, allowing "300 écus for the loss of a thumb or the first finger of the right hand, or an eye"2. We also have three different sets of pirate articles, although none of them specifically mention recompense for a lost eye.

We do have several accounts that mention pirates who were missing an eye, even if their articles do not take them into account. Two of them were pirate captains who lost their eyes during the golden age of piracy.

The first is the man who was quoted at the very beginning of this discussion: Pirate Captain Samuel Burgess. Burgess was a member of William Kidd's crew and was active around Madagascar from 1690 to about 1716. Unfortunately, his eye appears to have been lost because of an illness rather than anything as exciting as a cannon ejected splinter or a bullet.

The second pirate captain was Philip Lyne, also discussed on the first page. He was originally Francis Spriggs' quartermaster after Spriggs had split off from Edward Low, but he appears to have deserted Spriggs to go off on

The Explosion of the Spanish Flagship in the Battle of Gibraltar

Artist: Cornelis Claesz van Wieringen, (1622)

his own. Lyne was then "in command of a pirate sloop mounting ten carriage guns and sixteen swivels [swivel guns] and carrying forty men which was making captures off the banks of the Newfoundland coast in the summer of 1725."3 He lost his eye during a battle with "two sloops fitted out at Curacao"4 after which he was captured and hung without the eye or his other wounds being dressed.

There are a few other pirates with missing eyes mentioned in the book Pirates of the New England Coast. Neither of them were captains, so they don't immediately bring to mind the image of our little cartoon pirate, but they are period examples of pirates who lost their eyes, so they are of interest here.

The first was a member of Captain Thomas Pound's crew, who were captured at Tarpaulin Cove in Massachusetts. The sloop Mary captured Pound's pirate ship. "Richard Griffin, of Boston, gunsmith, embarked from Boston in Hawkins' boat; [he was] shot in the ear in the fight at Tarpaulin Cove, the bullet coming out through an eye which he lost".5 Griffen was eventually released, although no more is known about what became of him or his eye.

The second regular pirate with a missing eye was Tee Wetherly, a member of pirate Captain Joseph Bradish's crew. Bradish was another former member of Captain Kidd's crew who was in charge of his own ship. He and his crew were standing off the shore of Massachusetts

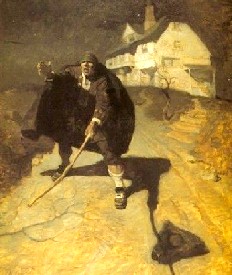

Rahmah ben Jabir from

The Pirates Own Book,

Charles Ellms

(1837)

when they were captured and put in jail. "On the morning of June 25th [1699], [jailer Caleb] Ray found the prison door open and Bradish and Tee Wetherly, one of his company, who had but one eye, were missing."6 Nothing more is known of Wetherly, so we can't even be sure how he lost his eye.

There is one other pirate captain we know of who lost an eye in battle: Rahmah ibn Jabir al-Jalahimah, who was active in the Persian Gulf in the early 1800s. Although he was active 100 years after the golden age of piracy, there are some elements of this one-eyed pirate that are interesting. Wikipedia tells us that he wore an eye-patch after he lost an eye in battle."7 Curiously, the only period reference I have found for him makes no mention of him having an eye-patch. James Buckingham tells us only that Rahmah;s face was "rendered still more [ugly] by several scars there, and by the loss of one eye."8 It is curious that in the contemporary illustration of him from The Pirate's Own Book, he does not appear to have an eye patch. Of course, we can only see one of his eyes.

This list does not suggest that pirates with missing eyes were common, nor does it suggest that they were uncommon. The only conclusion we can draw is that there is definitely proof that pirates lost their eyes during the golden age.

1 Alexandre Exquemelin, The Buccaneers of America, p. 71; 2 Pere Labat, The Memoirs of Pére Labat 1693-1705, p. 37; 3 George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, Pirates of the New England Coast, p. 287; 4 Ibid.; 5 Ibid., p. 70; 6 Ibid., p. 42; 7 wikipedia, Rahmah ibn Jabir al-Jalahimah, gathered from the internet 8/9/2012; 8 James Silk Buckingham, Travels in Assyria, Media, and Persia, 1829, p. 357-8

Pirate Eye Patch History - The Wounded Sailor

So if the period evidence doesn't support the pirate with an eye patch, where did he come from? The wounded sailor sporting artificial limbs and eye patches started to appear in the mid-18th century, about 50 years after the golden age of piracy. This figure frequently appears as a caricature, often in person of pensioners at Greenwich Hospital1, "an ancient Crown charity providing charitable support including annuities, sheltered housing and education, to serving and retired personnel of the Royal Navy and Royal Marines and their dependants."2 You will find several such illustrations below. (A thorough search of the internet will turn up several more.)

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson Vauxhall Gardens (1785) |

Artist: Dighton Greenwich Pensioners (1801) |

Artists: Isaac & George Cruikshank The Old Commodore (mid/late 19th c.) |

Once established, this archetype persisted throughout all of the 19th century and well into the 20th century. It is probably from here that the pirates - being sailors in the roughest part of the profession - first came to be associated with the eye patch. As the tall ships began to fade from the waters of the world, so did the image of the wounded, pensioned sailor. Modern ships were safer in many different ways, making it less likely that a sailor would be wounded at sea.

1 As suggested by David Fictum in Treasure Island, pyracy.com, 7/31/12; 2 www.grenhosp.org.uk, Welcome, gathered from the internet 8/9/2012;

Pirate Eye Patch History - The Wounded Pirate

Artist: N.C. Wyeth, The Blind Pew (1911)

As the pensioned, wounded sailor left the stage, the wounded pirate appears to have taken his place.

Many of the modern pirate tropes can be traced back to Robert Louis Stevenson's book Treasure Island. Pirate lore gained several things from this novel which, while they may have been present in the world of real golden age pirates, were specifically tied to them until that book made the link more definitive. From Stevenson's story pirates became associated with legless men, parrots on their shoulders, treasure maps to buried loot, walking the plank, the sing-songy dialect and the dreaded black spot.

Although the book didn't have any eye-patched pirates, it did have a blind one who may well have inspired some Hollywood movie-makers to add the patch first seen in the caricatured images of the retired and pensioned sailors found in the previous 150 years of imagery.

Joe as a pirate, The Buccaneers, Our Gang (1924)

Eye patched sailors, particularly pirates, began to appear in a medium which was a natural extension of caricatures: the cartoon. Sailors of old shown in cartoons during the 20s, 30s and 40s began to appear sporting the tell-tale black patch that indicated an eye had been lost.

David Fictum pointed me to an old 1934 black and white Mickey Mouse cartoon called Shanghaied in which the entire crew of the villain's ship sported eye patches. David also referred me to a 1924 Our Gang film short called The Buccaneers. Joe, one of the gang, wore a costume which featured a head scarf and the signature black eye patch.1

This emblem of the rough and tumble life of seamen and pirates continued throughout the cartoon world from that time forward. Almost any modern cartoon or kid's show featuring a pirate is sure to include it to help let the audience know what they are seeing.

Whatever the reason for the eye patches' popularity when showing pirates, it appears to have resonated with audiences beginning as far back as the mid/late-1700s. Although I found no proof in the period literature for the eye patch being used on pirates or sailors, it would be an easy and cost-effective way to cover a damaged eye. Since we have period evidence of pirates with missing and damaged eyes, it is likely they wore eye patches, at least when they were on land and didn't want to horrify the local residents. Still, since no proof has yet been produced for it, there is room for doubt.

1 On-line discussion with David Fictum, 8/3/2012