Cupping Therapy Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 <<First

Cupping Therapy During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Cupping Therapy Procedure

On the surface, the procedure for cupping seems fairly simple; put a match inside of the cupping vessel to burn the oxygen and then place the glass on the patient's body and let nature do her work. For wet cupping, several incisions are made before applying the cupping glass. Naturally it wasn't quite that simple. Audrey Davis and Toby Appel note, "In the hands of an inexperienced physician or surgeon, [wet] cupping could be highly painful to the patient, and yet fail to produce the requisite amount of blood."1 Let's look at how the period surgeons performed cupping therapy.

1 Audrey Davis and Toby Appel, Bloodletting Instruments in the National Museum of History and Technology, p. 24

Cupping Therapy Procedure - Preparation

Photo: Jan Baptist Lambrechts

Assistant Warming Cupping Glasses in Preparation,

From Wellcome Museum, London, (early 17th c.)

As with any medical procedure, preparation was key to a successful cupping. French surgical teacher Pierre Dionis begins his explanation of cupping discussing how the patient should be positioned. He explains,

...we are to seat the Patient in the proper Posture, which depends on the Place where the Application [of the cupping glasses] is to be made: But as we seldom use them to any other Part than the Shoulder, we shall suppose them to be fixed on that Place. If the Patient is in a State fit to rise, we may place him in a Chair, with his Head inclining forwards, and rested on a Pillow laid on the Table before him; if he be in a Lethargy or Apoplexy [unconscious, sometimes due to a stroke], he must be laid on his Belly...1

Sea surgeon John Atkins recommends marking the patient's skin with "the

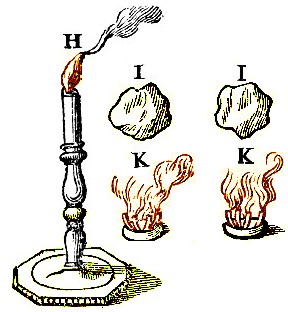

Items Prepared for Cupping, From Cours

d'Operations,

by Pierre Dionis, Fig. LVII, p. 841 (1740)

Diameter of the [Cupping] Glass" before heating the vessel. He then suggests that the surgeon "chaff [chafe] the Skin" before applying the cup.2

Military surgeon William Clowes reveals that before placing cupping vessels on the skin, he "used frications [friction]"3.

Dionis concurs, explaining that the part to be cupped is "to be rubbed hard with several very hot Napkins to warm the Parts and draw the greater Quantity of Blood, where we must not forget before-hand to cause a good clear Fire to be made, in order to the frequent renewal of the Napkins."4 (Napkins here refer to pieces of cloth.)

Sea surgeon John Woodall advised his readers to prepare the skin to be cupped by making sure it was "wet and rubbed well with hot water and a spunge, and the Cupping glasses also wet"5.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 474; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 181; 3 William Clowes, Selected Writings of William Clowes, p. 68; 4 Dionis, p. 474; 5 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 33

Cupping Therapy Procedure - Where Applied

Artist: Thomas Luny

Cupping, From Princely Court Library,

Waldeck Arolsen (1622)

As we have already seen, cupping glasses could be applied to any location on the body where the surgeon wanted to remove blood, provided the glass opening was small enough that it would seal at that site. French surgeon Pierre Dionis reported that in Germany, he saw cupping glasses "applied to almost all Parts of the Body"1. Hippocrates mentions cupping below the knee2, William Clowes talks about using them on the shoulders and hips3 and Woodall mentions placing them on the thighs, arms, hands and feet.4 Sea surgeon John Atkins sums it up nicely, stating that the glasses were "commonly put to Shoulders and Inside of the Thighs; or as other Cases may indicate, immediately to the Part affected."5

Various locations notwithstanding, surgeons during the golden age of piracy often directed that cupping vessels be applied to specific locations on the body based on the end they were meant to achieve.

Ambroise Paré explained that "when an humor continually flow’s down into the eies, [cupping vessels] may be applied to the shoulders with a great flame, for so they draw more strongly and effectually."6 He advised their use on the stomach "when anie gross or thick windiness [is] shut up in the guts" as well as the hypocondriac region (the

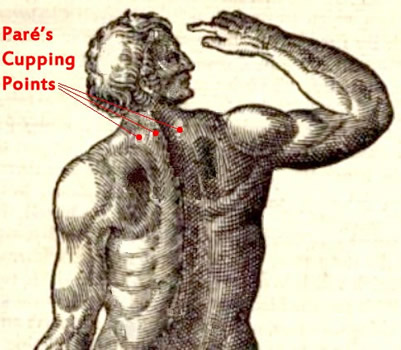

Cupping Points Specified by Ambroise Paré on the Back, From The Workes

of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 66 (1649)

abdomen near the bottom of the rib cage) "when as flatulencie [gas] in the liver, or spleen, swell’s up the entrail lying there under, or in too great a bleeding at the nose."7 He even recommended their application to the nipples for "a bastard pluresie [pleurisy - inflammation of the lungs] [where] cupping-glasses may be fitly applied"8.

The most popular place for cupping appears to have been the neck and shoulders. Although Paré lists a variety of cupping locations for various health issues, when he diagrammed the back of a man, he specifically identifies three spots on the shoulder, advising that this is where "we set the Cupping-glasses"9.

While explaining the cupping procedure, Pierre Dionis matter-of-factly says that "as we seldom use them to any other Part than the Shoulder, we shall suppose them to be fixed on that Place."10

Sea surgeon John Woodall similarly advises placing cupping vessels "on the upper part of the shoulder blades to draw back humours which oppresse the head, the eyes, or teeth."11

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 473; 2 Hippocrates, On Ulcers, p. 148; 3 William Clowes, Selected Writings of William Clowes, p. 68; 4 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 34; 5 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 181; 6 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 116; 7 Paré, p. 443; 1 Paré, p. 116; 9 Paré, p. 66; 10 Dionis, p. 474; 11 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 33

Cupping Therapy Procedure - Number of Cups Applied

The number of cups

Applying Multiple Cups to a Patient at a Public Bath, From Amusemens Des Eaux

De Spa, by Karl Ludwig von Pollnitz (1736)

applied is not usually specified. Pierre Dionis mentions affixing more than one cupping glass on a patient during his description of the procedure without suggesting the total number to be used.1 Sea surgeon John Woodall suggests that his readers should set "as many cupps ...as you see good"2.

In all the books under review, German military surgeon Gottfried Purmann is the only surgeon under study from this period to mention the number of cups to be applied to a patient. He does so when explaining how another surgeon cures wasting limbs. "Dr. Mays has done great Cures in this Nature by application of Cupping Glasses without Scarification [dry cupping]... [using] eight or nine of them for a considerable time"3.

Of course, since this is done by a specific doctor for a specific ailment, it should not be considered applicable outside of this instance. The number of cups a surgeon or physician used was left to the discretion of the surgeon based on the condition of the patient, the illness, the locations to be applied as well as any other factors that experience had taught were important to the procedure.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 474; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 34; 3 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 198

Cupping Therapy Procedure - Dry Cup Application

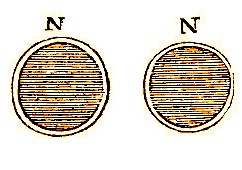

Dry cup application was fairly straightforward. Audrey Davis and Toby Appel explain in their book on bloodletting, "Once the torch was removed, the cup was allowed to sink of its own weight into the skin."1

Dry Cupping Glasses In Place

Surgical instructor Pierre Dionis agrees, noting that once "the Cupping-Glass [is] on the intended Place... it fastens immediately"2.

Sea surgeon John Woodall provides a little bit more insight and instruction on how the cup was to be applied for a dry cupping. He instructs the reader to use "the flame of a great candle... [placing the] candle close to the place where the Cups should bee set... hold your Cupping glasses over the flame a little, and thence clap it quickly on the place whilest yet the steeme of the light is in it, and it will be fast and draw hard… Further when you perceive [the cupping glasses] have drawne well, which by the blacknes and rising of the skin [inside the glass] you may easily see"3 then the procedure has been successful.

To improve the drawing ability of the glasses, a couple period authors advised keeping them warm. Dionis calls for "a very hot Napkin folded several times double" which the readers were ordered "to clap it on the Cupping-glasses, and a little while after we renew the Application of the Napkin, which we continue on till we think it proper to take off the Glasses"4.

Explaining the value of warming the cupping vessels, sea surgeon John Atkins says that "a Sponge of cold Water to the [Cupping] Glass, lessens its Attraction; [while] warm Water or a warm Room encreases it. And by the same Philosophy, a Bottle heated and inverted into Water, will attract above one Third full."5

The actual removal of the glasses after dry cupping was fairly simple. Atkins says "you need only press the Skin with your Finger to let in a little Air"6, something Dionis also recommends, almost word-for-word.7

1 Audrey Davis and Toby Appel, Bloodletting Instruments in the National Museum of History and Technology, p. 24; 2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 474; 3 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 33; 4 Dionis, ibid.; 5,6 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 181; 7 Dionis, p. 475

Cupping Therapy Procedure - Amount of Time Dry Cups are Fastened

Although none of the period authors indicate how long cups

Cupping The Temples, From Exercitationes Practicae Circa Medend

Methodum, by Frederick Dekkers, p. 208 (1694)

were to be left on the skin when dry cupping, some modern authors commenting on the procedure in the past discuss it. Naval historian and surgeon John Kirkup explains, "Professional dry-cuppers usually applied multiple cups at the same time, often left in position for thirty to forty-five minutes."1 When dry cupping the skin in preparation for future wet cupping, Audrey Davis and Tony Appel suggest that the cupping glass was set on the skin for a minute to cause the skin to swell.2

Davis and Appel also give an interesting account of what happened when the cups were left on:

If dry cupping was applied for ten minutes or longer so that the capillaries burst, the action of the cups was said to be that of a counter-irritant. According to ancient medical theory, the counterirritant was a means of relieving an affected part by deliberately setting up a secondary inflammation or a running sore in another part.3

Counter irritation was yet another way to draw the bad humors away from a remote location. The bursting of the capillaries would cause reddening of skin, which might also have been taken as a sign of the bad humors were gathering at the cupped site. Since no period author under study talks about how to measure a successful dry cupping, we can't know for certain.

1 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 399; 2 Audrey Davis and Toby Appel, Bloodletting Instruments in the National Museum of History and Technology, p. 24; 3 Davis and Appel, p. 31

Cupping Therapy Procedure - Wet Cup Application

Wet cupping was a bit trickier, particularly because it usually followed dry cupping almost immediately. Audrey Davis and Toby Appel give the clearest explanation of why this was problematic.

During the minute that the skin was allowed to tumefy [swell] under the cup, the scarificator was warmed in the palm of the hand in preparation for the most difficult part of the operation. It required great skill to manage torch, scarificator, and cups in such a way as to lift the cup, scarify, and recup before the tumefaction had subsided.1

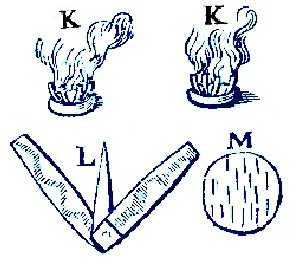

When scarifying the skin, incisions could be made by hand using a fleam/lancet or a multi-bladed scarificator.

Cupping Procedure Tools, The Sketch of 'M' Does Not Seem

to Accurately Reflect Dionis'

Clear Description.

From

Cours

d'Operations,

by Pierre Dionis, Fig. LVII, p. 841 (1740)

French surgeon Pierre Dionis gives a detailed explanation of how the surgeon was to properly puncture the skin by hand.

We then take the Lancet L, with which we make several Scarifications on the Place of the Circle [the round patch of swollen skin created during dry cupping], where we make three Scarifications, we continue mounting upwards, where we make four, then five above them, then four, and end with three, so that they are all interlac’d in one anothers spaces, in manner as represented by the Figures M"2

John Woodall advises the surgeon, "if you hold it fitting you may lightly and quickly scarifie it [the skin] with a fine Lancet, which truly is the best and profitablest instrument of the use"3. Woodall doesn't specify a pattern of incisions like Dionis. He does warn against making the scarifications in the skin too deep, saying that it "is not onely dangerous, but also painefull, and not Art-like"4.

For wet cupping, Dionis integrates burning of the air inside the cup with the placement of the cup, explaining "we light the Wax Candles [the four little sticks shown as K K in the above image] which we place on the scarified Places, and then over them apply the same Cupping-Glass"2. So Dionis advises placing the candle on the patient's body and then placing the cupping glass over it while wet cupping. He notes that some surgeons use burning tow fabric rather than candles, sagely explaining that "'tis much better to make use of the small Wax Candles stuck on a little round piece of Card, [because] they yield a greater Flame than the [burning] Tow, and consequently the Cupping-Glasses draw stronger, and we don't with these ends of Wax Candle run the risque of burning the Patient, as we do with the Tow."4

Artist: Wolf Helmhardt von Hohberg

Cupping The Shoulders (1695)

As the glass formed a seal on the scarified skin, the oxygen would be consumed in the glass by the flame of the candle, causing it to burn itself out. This would hopefully occur quickly enough prevent the burning of the patient's skin while creating as much of a vacuum as possible inside the cup. Such a complete vacuum should result in the maximum amount of drawing power possible.

It was a bit hard on the candles, however. Dionis explains that if the surgeon wanted to wet cup the location a second time, "we must have other Wax Candles, because the first being wetted with the Blood cannot be lighted again"5.

While putting the flame inside the cupping vessel on the body might have been effective, sea surgeon John Woodall protested against this method in any form. He explains,

Some [surgeons] set them on with [burning] towe, some with a small wax light set under them; some onely with the flame of a great candle, which my selfe use, and is not offensive nor painefull at all. Whereas the other waies the flame excoriateth often the part [damages the skin], and maketh new worke unseemely6.

The unseemly 'new work' Woodall mentions might also require burn treatment, which wouldn't instill confidence in the patient or observers.

Once the cups were on and extracting blood, the surgeon would need to monitor them to determine when they were ready to be removed. Dionis is a bit vague on how to judge this. He simply advised the surgeon to make sure the cups were filling with bloud "and when we judge there is enough, we call'd for a Vessel to put the Blood into, which is contain'd in the Cupping-Glass."7

Modern authors Davis and Appel state, "When the cups were two-thirds full, they were removed and reapplied if necessary."8 It is not clear where they got this measure from, although it makes sense that you wouldn't want the cup to be too full or removal would be messy.

Woodall gives the most explicit instructions for knowing when wet cupping should be stopped, telling his readers to draw "as much bloud as you see good, and when no more bloud will come, and ...you thinke it time to take them away, which is knowne by a yellow water which commeth at the last"9. What this 'yellow water' might be is a mystery.

1 Audrey Davis and Toby Appel, Bloodletting Instruments in the National Museum of History and Technology, p. 24; 2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 474; 3 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 33; 4 Dionis, p. 474; 5 Dionis, p. 475; 6 Woodall, p. 33-4; 4 Dionis, p. 474-5; 8 Davis and Appel, ibid.; 9 Woodall, p. 34;

Cupping Therapy Procedure - Post-Cupping Treatment

Some surgeons recommended post-operative

Photo: Amy Selleck - Post-Operative Cupping Bruises

medicinal treatments for wet cupping. Most of them involve cleansing the site with various liquids and then treating the wounds, often with a healing ointment.

Hippocrates advised, "In all such cases [of scarification] the parts are to be bathed with vinegar, after which they are not to be wetted; neither must the person lie upon the scarifications, but they are to be anointed with some of the medicines for bloody wounds."1

Sea surgeon John Woodall says that after removal of the cups "it is time to wash the places with faire water [clean, pure water2] where the cupps stood, and dry them [the cupping locations on the body] with a spunge or cloth, and onely anoint them with Ung. Album [white unguent] once, and they will bee whole."3

Fellow sea surgeon John Atkins suggests that the surgeon "wash the Scarifications with warm Wine and Water, and apply Ceratum Diapalm.[Ceratum Diapalmae – a drying paste made with wax, oil, hogs-fat, palm oil, litharge, and zinc sulfate.]"4

Post-Operative Cupping Plasters - The Lines

Represent the Plaster on the Bandage,

From

Cours

d'Operations, by Pierre Dionis,

Fig. LVII, p. 841 (1740)

French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis gives the most complete description of post-operative treatment of scarified wounds, advising his students,

The Operation ended, we are to dry up all the Blood very clean, washing the Shoulder with warm Wine, and lay on the two Plaisters N N, on the two Places where we have made the Scarifications. They are of burnt Ceruse [white lead pigment], because nothing is now to be done but dry them up; they [the dressings] are to be renewed some Days after, which is to be done till the Patient is perfectly cured.5

Although the period manuals don't discuss the care of the cupping and scarifying tools post-op, Audrey Davis and Toby Appel do comment on how the care of the scarificator: "Scarificator blades could be used some twenty times. After each use, the scarificator was to be cleaned and greased by springing it through a piece of mutton fat."6 While we cannot be certain period sea surgeons used scarificators for cupping, it is still an interesting insight into the care the tools received.

1 Hippocrates, On Ulcers, p. 148; 2 Thanks to Bryan Chabot for his help determining and proving this; 3 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 34; 4 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 181; 5 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 475;