Cupping Therapy Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Cupping Therapy During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Cupping Therapy Tools

Photo: Mission - A Variety of Cupping Glasses and a Scarificator

The tools for cupping were fairly simple. Several military and sea surgeons specify cupping glasses in the list of surgical implements1 and all the sea and military surgeons under study advised their use, so cupping glasses would have been included in a sea surgeon's tool chest.

For dry cupping, the practitioner required only a cupping vessel and a match. Some procedures called for wetting the rim of the glass and the patient's skin with hot water and a sponge2, so those might also be needed.

Wet cupping was a bit more complex, requiring all the tools needed for dry cupping as well as a something to make the incisions. The optimal tool for incising the skin would have been a scarificator, although this was a fairly sophisticated tool for the time and thus more expensive than the alternative - lancets/fleams and possibly a fleam mallet to tap them into the skin. In addition to these items, the surgeon would also want to have cloth to clean the blood and possibly styptic medicines to stop the bleeding.

1 See for example William Clowes, Selected Writings of William Clowes, p. 148 and John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 22; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 33

Cupping Therapy Tools - Cupping Vessel Material

Cupping vessels were made of several different types of material during the golden age of piracy. Medical instrument historian John Kirkup explains that brass and pewter were still in use during the eighteenth century.1 In their review of cupping vessels at the Smithsonian Institute, Audrey Davis and Toby Appel state, "The use of cattle horns for cupping purposes seems to have been prevalent in all periods up to the present."2

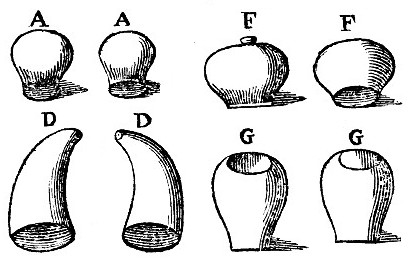

Cupping Vessel of Various Materials - Dionis Explains that A A "are called Cornets,

because made of horn" [used in Italy], D D are Open Ended Animal Horns Used By

the

Practitioner to Physically Suck the Air Out and then Capped with Wax. F F and

G G

Are Various Sized Glass Cupping Vessels Used in France,

From Cours

d'Operations,

by Pierre Dionis, Fig. LVII, p. 841 (1740)

Pierre Dionis explains to his students that brass and pewter cups could be used and shows horns in his cupping tool diagram. However, he also explains that the non-glass vessels were used in other countries European countries.3 He notes, "we at present make use of no other [types of cupping vessels] but those of Glass, because they are most proper, and that being transparent we see what passes in them, and by what means know whether there have issued out a sufficient Quantity of Blood before we take them off."4

Davis and Appel point out that the metal cups' "main virtue was that they did not break and thus could be easily transported. For this reason, metal cups were especially useful to military surgeons. Brass and pewter cups were common in the eighteenth century, and tin cups were sold in the late nineteenth century."5 This sounds logical. However, the surgeon's chest would be filled with glass bottles to hold medicines, so military and sea surgeons would at least be accustomed to dealing with glass and may have agreed with Dionis that glass vessels were useful in monitoring wet cupping. It is notable that cupping vessels are usually called 'cupping glasses' by sea surgeons in the period literature6, suggesting (although not definitively proving) that they were made from glass.

1 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 398; 2 Audrey Davis and Toby Appel, Bloodletting Instruments in the National Museum of History and Technology, p. 17; 3 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 473; 4 Dionis, p. 471; 5 Davis and Appel, p. 19; 6 For examples, see John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 22; John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 33 and John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 181

Cupping Therapy Tools - Cupping Vessel Size

Cupping vessels were produced in a variety of different sizes. Ambroise Paré suggested that the surgeon "make choice of greater and lesser Cupping-glasses according to the condition of the part , and contained matter.

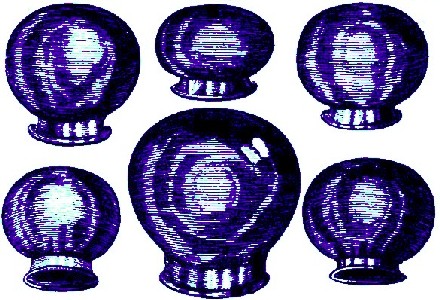

Different Sized Cupping Glasses, From Exercitationes Practicae Circa Medendi

Methodum

by Frederici Dekkers, Table1 (1694)

But to those parts whereto these cannot by reason of their greatness bee applied, you may fit horns for the same purpose."1 Paré seems to be suggesting that the cupping glass be chosen based on the size of the wound it was meant to treat as well as to provide a vessel large enough contain all the 'matter' extracted from the wound during wet cupping.

Sea surgeon John Woodall says that the size of the cupping glass depends on the body part to which the vessel is to be applied. "Large and wide Cupps are fittest on the thighs, lesser on the armes, and the least for the hands or feete."2 Woodall warns that "you must have your Cups fit and not too wide for the place you would set them on, or else they will not take any hold"3.

French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis has a slightly different take on cupping glass size. He advises his readers to "at least have two sorts of Cupping-Glasses of different Sizes; the least F F [see the image in the previous section], for children or those Cases when they would make but a light Attraction, and the larger G G, for grown Persons or those Occasions which require a strong Suction."4 Here, it is the amount of vacuum that can be formed that interests Dionis, suggesting that larger vessels would pull humors more forcefully during cupping.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 443; 2,3 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 34; 4 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 473;

Cupping Therapy Tools - Lancets and Fleams for Scarification

Lancets or fleams were small knives used in cupping therapy for scarification to make incisions in the skin. They could be inserted into the skin by hand or tapped in using a small bat-like fleam mallet. They were fairly popular during this time for sea and military use. Writing in the late 17th century, military surgeon Richard Wiseman mentions their use in conjunction with scarification several times.1 When describing the procedure for wet cupping, sea surgeon John Woodall advises his readers to "lightly and quickly scarifie it [the skin] with a fine Lancet, which truly is the best and profitablest instrument of the use"2.

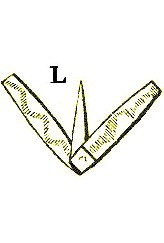

In his procedure for wet cupping, Pierre Dionis advises his readers to "take the Lancet L, with which we make several Scarifications on the Place of the Circle [made by the cupping glass]"3. While explaining a German method for scarification that he witnessed, Dionis gives a rather fascinating description of the use of a fleam/lancet. "[T]hey make the Punctures with a little Phlegm [Fleam], which they hold in one Hand, fillipining [propelling] it with the other, they make these Punctures in what shape they please, ranging them next one another; some of them represent the true Lover's Knot, others a heart, and others the Cyphers of their Mistresses Names, conform to the Desire of the Person cupped."4 Scarifying the skin to create designs is still practised today.

Dionis' Lancet/Fleam, From Cours d'Operations, by Pierre Dionis, Fig. LVII, p. 841 (1740) |

Photo: Mission Photo: MissionThe Author's Lancet/Fleam Set and Case with a Fleam Stick to Tap the Blades Into the Skin |

Artist: Prosperi Alpini Artist: Prosperi Alpini Detail of Scarifying a Man's Legs with a Lancet By Hand, From De Medicinea Aegyptiocum (1719) |

1 See Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 86, 115 & 128; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 34; 3 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 474; 4 Pierre Dionis, p. 473

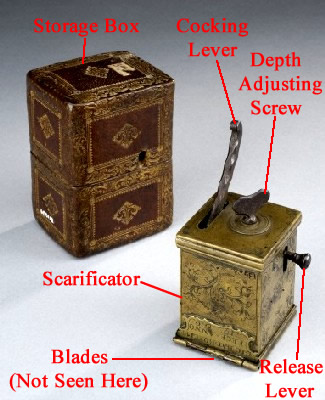

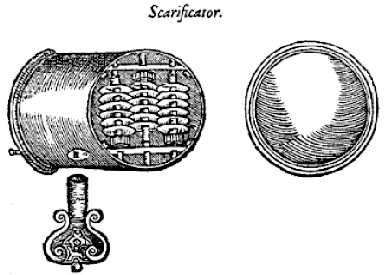

Cupping Therapy Tools - Scarification with the Scarificator

A

Italian Scarificator, From the Wellcome Museum, London (1669)

scarificator was a mechanical device that was used to make multiple incisions at one time, which both saved the surgeon from having to make multiple, painstaking incisions in the patient's skin and saved the patient from the drawn out pain of having repeated cuts made in their skin.

The spring-loaded mechanical workings of a scarificator were fairly sophisticated for the time, suggesting the devices would have been more expensive than lancets.

The operation of the device was fairly simple, however. The surgeon would begin by adjusting the depth of the blades using a depth adjusting screw located on the top of the scarificator. This moved the base of the scarificator up and down, adjusting the depth to which the blades could protrude..

Audrey Davis and

Photo: Mission

The Author's Scarificator With Blades Shown

Tony Appel cite data from Samuel Bayfield's 1823 book, which explained that "the blades of the scarificator were generally set at 1/4" If cupping behind the ears, they should be set at 1/7", if on the temple at 1/8", and if on the scalp at 1/6"."1 (They must have had some interesting rulers.)

Once the depth was set, the surgeon would place the bottom of the scarificator on the patient's skin. Then he would pull cocking lever, causing the multiple blades to rotate 180 degrees. They made a number of incisions in the patient's skin as they rotated through it. The surgeon would then remove the scarificator from the patient's skin press the release lever on the side of the device to reset the blades back to their original position. The scarificator would be stored in it's box when not in use to protect it.

Spring Fleam Set - Wellcome Museum, London (1701-18)

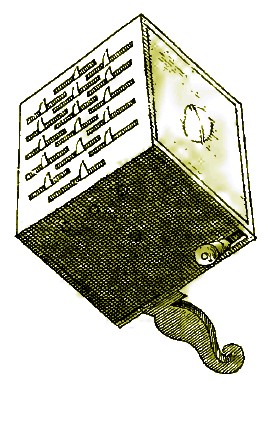

Surgical tools were designed by various small shops , so there was a great deal of variance in design and style of scarificators. The first devices appear to have been round based on a sketch of one in Ambroise Paré's book. Round scarificators continued to be produced well into the 19th century and possibly even the 20th centuries.2 A round scarificator had the advantage of being the same shape as the the area that would have been raised by a cupping glass when dry cupping before scarification. However, by the 17th century and into the 18th century, square scarificators seemed to have gained in popularity.

The number of blades on a scarificator varied widely. Writing for the New York State Journal of Medicine, Gilbert R. Seigworth says that scarificators had from 1 to 20 blades, although the 12 blades seems to have been the most common.3 A one bladed scarificator was also known as a spring fleam and should probably be considered in a class of its own since it was usually described as being used for opening a vein. Excluding it, the minimum number of blades in a true scarificator appears to have been four.4

There is some confusion as to when the scarificator came to be used in cupping. In their book on bloodletting instruments in the Smithsonian Institute, Davis and Appel reason

Ambroise Paré's Scarificator, From Opera Ambrosii Paraei Regis Primarii et

Parisiensis Chirurgi, p. 365, (1582)

that scarificators was not used until near the end of the golden age of piracy. "The instrument was not found in Dionis (1708), but it did appear in Heister (1719) and in Garengeot (1725). Thus it appears that the scarificator was invented between 1708 and 1719."5

In fact, the device appears in Ambroise Paré's book Opera Ambrosii Paraei Regis Primarii et Parisiensis Chirurgi, published in 1582. (An image of which Davis and Appel show in their book!6) Paré does not suggest the use of the scarificator in cupping therapy, however. He suggested it for treating gangrene, although he does mention scarifying in conjunction with with cupping.7

The scarificator shown in the photo seen above from the Wellcome Museum in London is of an Italian scarificator that the museum has dated to 1669. (The date is actually inscribed on the casing.) So the scarificator definitely existed before 1708. They may have meant to say that the scarificator was not provably used for scarification until Heister noted it in 1719.

Even this is open to debate, however. In his book The History and Evolution of Surgical Instruments, Charles John Samuel Thompson explains,

In Bagnios of London much frequented in the 17th century, a cupper was generally in attendance, who according to the bills of the time would perform the operation for '2/6 [2 shillings and six pence] by the old, or the new way.' The latter referred to bleeding with the scarificator, the box-shaped instrument with many short blades that came into use towards the end of the seventeenth century.8

A Square Scarificator, From

A General System of

Surgery, Plate 12, by Lorenz Heister (1759)

Based on this, it is the scarificator was most likely in use as a wet cupping device throughout the golden age of piracy (defined here as 1690 - 1725).

This does not mean it would have been used on ships. Many of the surgeons serving at sea would be young and newly trained and would most likely have relied on the stipend they received from the ship to purchase of tools. Although cupping was performed on ships at this time, the cost of the scarificator would would make it less desirable for a man with a budget than lancets. Other tools such as a good amputation set and a skull trepanning kit would have been of greater use to sea surgeon than the scarificator.

Of the surgical authors who had served at sea during this period, only one of them suggests the use of the scarificator at sea. The rest discussed lancets/fleams. Sea surgeon John Woodall advised the use of a fleam/lancet for scarification.9 Although John Moyle does not identify the tool he used for scarifying, he includes lancets in the same lists as cupping glasses when listing tools the sea surgeon should bring with him.10 Other military surgeons also advise the surgeon to have lancets/fleams in the surgical tool kits.11

The lone sea-surgeon who talks about scarificators is John Atkins, who, although he served in the Royal Navy during the golden age of piracy, wrote his book after it had ended. Still, his recommendation is most hearty. "The Scarificator is best reckoned for this Work, because it makes all the Wounds at once, and with less Apprehension than our common Method at Sea, by a single Lancet."12 Yet the weight of period evidence favors lancets or fleams for scarifying at sea during this period. Some sea surgeons may have had a scarificator, but most probably would not.

1 Audrey Davis and Toby Appel, Bloodletting Instruments in the National Museum of History and Technology, p. 24;2 "19th C French Round 10 Bladed Scarificator", Physick.com, gathered 11/16/14; 3 Gilbert R. Seigworth, "A Brief History of Bloodletting", PBS.org, gathered 11/16/14; 4 "Scarificators", Phisik.org, Published 11/14/11, Gathered 11/17/14; 5 Davis and Appel, p. 22; 6 Davis and Appel, p. 78; 7 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 233; 8 Dr. Charles John Samuel Thompson, The History and Evolution of Surgical Instruments, p. 81-2; 9 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 34; 10 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 22; 11 For example, See Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 86 and Guliielm. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, p. 22; 12 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 181