Cauterizing Tools Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Cauterizing Tools of the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Actual Cauteries

"In persons

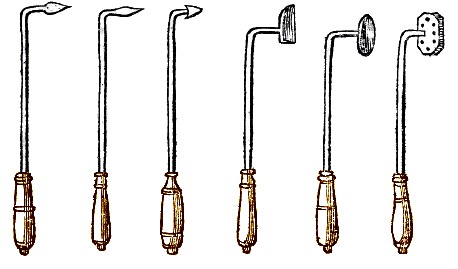

A Set of Actual Cautery Irons, from Cours d'Operatione by Pierre Dionis, p. 466

affected with chronic disease of the hip-joint, if the bone protrude from its socket, the limb becomes wasted and maimed, unless the part can be cauterized." (Hippocrates, Aphorisms, p. 141)

Actual Cauteries were heated metal probes of various shapes and sizes that stop bleeding and the spread of gangrene by burning the patient's skin. They have been around since antiquity, as can be seen in the above quote.

Although there was a decided move away from this harsh form of treatment during the golden age of piracy, cautery irons were still included amongst a sea surgeon's tools. So let's take a look at what might have been included in typical surgeon's kit during this time period. We will begin by looking at some of the properties of cauterizing irons and then examine the specifics of the tools that were actually used.

Actual Cautery Properties

The Author's Cautery Irons and Brazier

"It was then put upon me: and at their desire I undertook it, and gave directions for the making actual Cauteries of various sorts, some Bolt-like, others like Chisels, others of other fashions. ...That done, we met again, and had the Instrument-maker attending to heat the Cauteries, and mend or alter them as occasion should offer." (Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 113)

There were several considerations about the actual cauteries that a surgeon would have included in his tools. Among the things to be considered were the number of cauteries the surgeon was to have avaiable, the size and composition of the tools, the temperature a cautery was to attain and the design of the head for different types of operations.

Actual Cautery Properties - Number of Cauteries

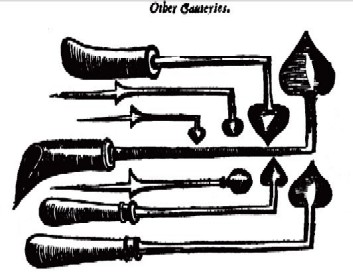

"The

Cautery Irons, Set 1, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgeon

Ambrose Parey, p. 485 (1649)

irons came in all shapes and sizes. If a surgeon had the same type of wound again and again and the cauterising irons he had were not of the right shape, he would get a new one made up." (Rory W. McCreadie, The Barber Surgeon's Mate of the 16th and 17th Century, p. 47)

A surgeon could have a large number of cautery irons in his kit. French surgeon Ambroise Paré revealed that as far as irons were concerned, "their varietie in figure is so great, that it cannot be defined, much less set down in writeing; for they must be varied according to the largeness of the rottenness, and the figure and conformation of the fouled bones."1 Paré was the same surgeon who discovered that a hot oil cautery was inferior to gentler methods, but he did not shy away from the use of the actual cautery, including a wide variety of drawings of them in his Works, as can be seen here.

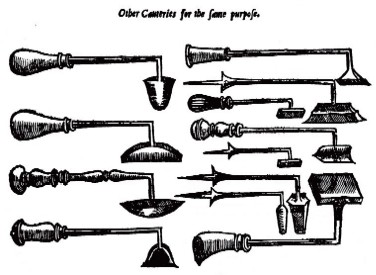

Cautery Irons, Set 2, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgeon

Ambrose Parey, p. 486 (1649)

French surgical teacher Pierre Dionis may have even been referring to Paré's book when he observed that the "first Chirurgeons have left us an infinite variety of these Actual Cauteries; but tho' they have left us a great many, they have yet also left us the liberty of inventing new ones on proper Occasions"2. You may recall that Dionis was not a fan of actual cauteries, so it is not surprising that he only chose to detail six of them in his book.

French surgeon Jacques Guillemeau likewise explains, "It is impossible for the Chyrurgiane to presente in this place all the figures, & portraytures of the Cauteryes, wherewith he must co[n]tente himselfe for he must sometimes cause them to be forgede accordinge to the requiringe of the Operatione, & the parte, where on he intendeth to use the same"3.

Guillemeau

Cautery Irons, Set 3, from The Workes of That Famous Chirurgeon

Ambrose Parey, p. 486 (1649)

makes another interesting observation about the number of irons required. "The Cauteryes are alsoe differing, in theire numbre, for at sometimes we applye but one, sometimes two, thre, four, yea alsoe fifteen at one time, as Ætins [Aëtius of Amida, 5th/6th century Byzantine phyisician] co[m]mandeth us, to the curing of the ulcerations of the Brest."4 This suggests that a surgeon could have multiple versions of the same cautery if he felt they were required for particular wounds. Pierre Dionis also explains that it is sometimes necessary to have a second cautery ready and waiting during operations.5

Based on the observations from these three French surgeons, it is understood that a wide variety of cauteries could be included in a surgeon's collection. If he found himself confronted with a wound that required a different size or shape of cautery iron, he would have it made.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p.585; 2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 467; 3 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, p. 23; 4 Guillemeau, , p. 40; 5 Dionis, p. 311;

Actual Cautery Properties - Size and Composition

Only one author addresses the size and composition of cautery irons, which is somewhat astonishing. It may have been that such things were common knowledge, especially since surgeons were required to apprentice themselves to practicing surgeons for seven years. Such an extensive apprenticeship would give the student a good working knowledge of the tools when he was ready to have his own made.

Cautery Size and Depth

Differences

Fortunately for those of us who are hundreds of years away from the actual tools and their use in practice, Jaques Guillemeau gives us some details. He explains that the "essence, & beinge of these Cautereyes, co[n]sisteth in theire forme, & figure, wherefor some ther are which be ...greate, smalle, deepe, or not deep"1. With regard to cautery size, he reveals that he tends to prefer "Cautereyes which be reasonable shorte, because those which are of to greate a longitude, & bignes, doe affrighte the Patient, as allso those which are too longe can not so easilye conductede, & rulede, because they doe most co[m]monly vacillate,& turne this way, & that way in the hande."2 Another factor here would seem to be that longer cauteries would put the surgeon further away from the place he was cauterizing, making accuracy more challenging.

Deepness of the cautery could refer to both the length of the shaft between the cautery head and the instrument handle as well as the depth of the head of the tool. Although Guillemeau does not discuss the length of the shaft, it would again seem to be a practical consideration for the surgeon who wants to be at a distance where he can easily see his work, but not too close to the burning skin. With regard to the depth of the head of the instrument, Guillemeau notes that tools must differ "in theire depthe, or shallowness: for we neede sometimes to cauterize the skinn only"3 as opposed to penetrating deep into ulcers or cauterizing rotting bones in the skin.

A Gold Cautery?

Cauteries could also made from different materials. Elizabeth Bennion, writing about ancient instruments explains, "Most of the cauteries were of iron but a few seem to have been gold"4. Guillemeau explains that ancient surgeons and physician were "of opinion, that the cauteryes of gould caused lesse payne, & weare [were] farre more easyer to be suffered, that alsoe the Cauterized place, shoulde not voyde soe much matter, and the adustio[n] [burning] is not soe daungerouse, because gould amongest all other mettles is the moste temperate, wherfore it burneth not so violently, as Iron, because it is not soe co[n]densated [condensed] of substance"5. He actually has a point here: gold does not hold heat as well as iron, so a gold cautery would not be as hot when applied and would be less painful. One has to wonder if it didn't melt when left in the fire too long, however.

Guillemeau says that some cauteries were also made of silver and copper. He doesn't give further details about silver cauteries, but he explains that the copper tools do "not soe closely burne, or cauterize, as those which are made of Iron, because the copper, is not so solide of matter, wherfore we desireing stro[n]glye, & violentelye to cauterize we must take such cauteryes, which are made of conde[n]st, & most firmest matter, & substance." This again occurs because copper doesn't hold heat as well as gold.

1 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, p. 40; 2 Guillemeau,p. 23; 3 Guillemeau,p. 40; 4 Elizabeth Bennion, Antique Medical Instruments, p. 184; 5 Guillemeau,p. 40; ;

Actual Cautery Properties - Temperature

The temperature of the cautery when it was being applied was also important. As explained in the previous section, the type of metal from which the cautery was made could impact how long it held heat. Jacques Guillemeau recognizing this, further explaining that "amongest the cauteryes, (considering the matter wherof they are composed) ther be some which are quicly heated) and some which continue longer hott, then others"1. As he detailed in the previous section cauteries made from metals like gold and copper would be cooler upon application, all other factors being equal.

This aside, the general concensous seemed to be that cauteries should be "made hott, & glowinge"2 as Guillemeau explains. Based upon that, It would see that iron cauteries would be most useful during surgery. John Woodall concurs with Guillemeau, advising the surgeon's mate trying to stop a bleeding vein

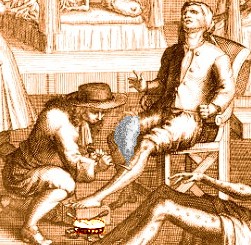

Leg Cauterization from The Martyrdom of

Mercury by J. Sintelaer, p.104 (1709)

to "apply to the end of the Veine an actuall Cautery, a small one will serve, but apply it very hott, and not all over the wound, onely to that Veine if you can which bleedeth"3.

Sea surgeon John Atkins provides more detailed insight into the problem of the temperature of a cautery.

And in applying it, we are to observe, if not hot enough, it makes no Eschar [scar of dead, burned skin], giving only unnecessary Anguish to the Patient: And on the other Side, if too hot, it then makes an Eschar indeed, but separates and loosens it at the same Time, the Security being intended being either way equally eluded. But this is an Inconvenience that may be obviated by a quick or slow Application, as the Surgeon shall judge to the Degree of Heat in his Button [cautery iron].4

Atkins doesn't explain how the reader can accurately 'judge the Degree of Heat'. This is probably also something that would be taught during a surgeon's seven year apprenticeship where he would have been tutored in how to recognize when a cautery iron was ready for application.

1 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, p. 40; 2 Guillemeau, ibid.; 3 John Woodall, Woodalls Viaticum, p. 6; 4 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 122

Actual Cautery Properties - Heating Cauteries: Chafing Dishes

Heating Cautery Irons

from

The Martyrdom of

Mercury

J. Sintelaer, p.104 (1709)

While heating the cautery irons was important, most of the surgeons do not talk about how this was done. If they discuss it at all, they mention it in the context of an operation. When discussing cauterizing iron use in a hernia operation, Richard Wiseman says, "actual Cauteries of different sorts ready heated in some corner of the Chamber"1 without further explaination..

One author does specifically tell us how this was done; our surgical instructor Pierre Dionis. When explaining an operation to cauterize a lachrymal fistula - an fistula of the eye - Dionis says that if the surgeon believes the first cautery iron used doesn't work "we then apply a second Cautery; for which Reason we are always to lay two in the Chafing-dish, full of Fire to be heated."2

According to the Journal of Antiques and Collectibles Website, "Chafing dishes and braziers were made of a thin metal, often brass or copper, spun or pressed or hammered; the pots suspended over them were similarly constructed for lightweight and so as to permit sensitive heat transmission."3

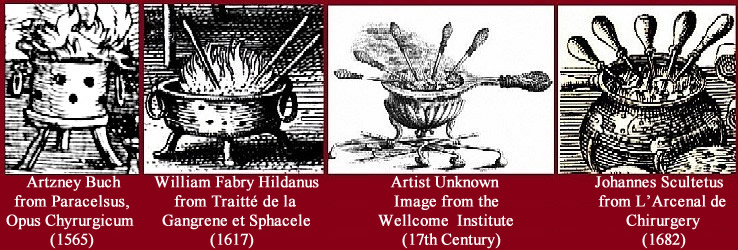

Unfortunately, the surgical texts themselves do not provide information on the chafing dishes used to heat actual cauteries. Fortunately, their illustrations make up for this. Nearly every cauterization drawing or woodcut shows a chafing dish, always three-legged and usually squatting near the feet of the patient with flames shooting out of it as can be seen in the images below. A handful of cautery irons can often be seen nestled in the glowing hot coals resting in the bottom of these braziers.

Dionis' Cautery Heating Chafing Dish, from Cours d'Operations, p. 559 (1733)

This brings us to the primary problem of sea surgeons using actual cauteries. James Yonge explains that it is "difficult, if not impossible [for actual cauteries] to be used in the great fights at Sea; partly from the hazard and inconvenience of fire; partly from the tediousness of heating it, and the aptness

to flame, while so heating, which would be very perilous"3.

Ships in a fight were often bombarded with cannon fire, which could easily upset a chafing dish like the ones seen here. Ships, being made of wood, caulked with cotton and oakum (hemp fiber soaked in pine tar) and having canvas sails, were giant fire hazards. It is unlikely that actual cauteries would be used unless a ship was at rest or sailing in very calm waters, because of the danger of the chafing dish required to heat them being upset.

Some Illustrations of Chafing Dishes Being Used to Heat Cautery Irons |

1 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 104; 2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 311; 3 Alice Ross, Braziers and Chafing Dishes, Journal of Antiques and Collectibles, March 2002, gathered from the internet 8/18/13; 4 James Yonge, Currus Triumpalis, é Terebinthô., p. 51-2