Animal Bite and Sting Wound Treatment Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

Treating Animal Bites and Stings in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Venomous Animal Wound Treatment: Mechanical Poison Removal

Venomous Animal Wound Treatment: Mechanical Poison Removal - Actual Cautery & Scarification

Actual cauterization involved heating an iron tool red hot and intentionally burning the skin to make a wound that was difficult to heal so that the poison could escape.

The Pain of Cautery, From The Martyrdom of

Mercury, by J. Sintelaer, p. 104-5 (1709)

Physician Stephen Bradwell explained that the surgeon could "burne the wound with a hot Needle or Bodkin: and it is the best way, both to consume the venomous matter before it goes further, and also to keepe the orifice open, which must be so kept, till there be not likelihood of venom left in the affected part."1 However, Ambroise Paré also warned that "this must bee done before the poison enter’s far into the bodie, for otherwise Cauteries will not onely do no good, but further torment the patient, and weaken him to no purpose."2

Both Paré and Bradwell advise scarifying the scab or 'eschar' created by cauterization. This is performed by making several small incisions in it. Bradwell explains this best: "Upon this burning, there will grow a crustie scab, round about which the place must be scarified with the sharp poynt of a Pen-knife, that the corrupted bloud may have issue."3 Paré adds that scarifying will "caus the speedier falling away of the Eschar... thus the poison will the sooner pass forth.”4

Once the wound was scarified, medicines were applied in an effort to keep the wound from closing. Bradwell recommended regularly washing the wound with heated sharp vinegar, white wine or a solution of urine &salt-water to further this end.5

Yellow Basilicon Ointment

He further prescribed that the swollen area around the wound be covered with " a Playster made of Turpentine, Wax, blacke Pitch and Pitch of Burgundie [pine resin]: And into the wound put some Lint dipped in Unguentum Basilicon [an unguent containing oils, resin & lard among other things], mixed with a little burnt Alum, to keepe the wound open."6 Paré instructed the surgeon to "Let drawing plasters bee laid to the wound and neighboring parts, made of Galbanum, turpentine, black pitch, and other gummie and resinous things."7 Notice the similarity of ingredients used.

With an eye towards removing the eschar, Bradwell suggested that "when the scab is growne dry, you must annoynt it with fresh Butter alone, or fresh Hogs grease mixed with it, & having so loosened it, take it off"8.

Once the eschar or scab was removed or fell off, the was to be kept open so that the poison could continue to be drawn out. Paré said that the surgeon should apply to the freshly opened wound basilicon "quickened

Photo: CDC - An Eschar

with a little [Red Mercury] Precipitate, for it is very effectual in these cases, for that it draweth forth the virulent sanies [serum, blood or pus] out of the wound, neither doth it suffer the wound to bee closed speedily."9 Red mercury precipitate was sometimes used in basilicon by physicians specifically to cause a wound to form a scab or eschar.10 Paré adds that the wound can also be kept open using "a piece of spunge, or a root of Gentian or Hermodactyl, or som acrid medicine, as ægyptiacum, or [red mercury] Precipitate mixed with the powder of Alum, or a caustick beaten to powder."11

In a similar vein, Military surgeon James Cooke ordered "the Eschar is presently to be removed, and the Wound to be cured by degrees; which is to be kept open for forty days: to which end, a Pea may be put in, on which lay an attractive [drawing] Plaister.”12 There are some interesting points about Cooke's recommendation. First, the suggestion to place a pea in the wound and leave it there for several weeks was to create a type of fontanel called an issue. Issues were specifically designed to irritate a wound so that it would seep unwanted humors. Second, like Paré and Bradwell, Cooke advises the use of a drawing plaster, such as Paré and Bradwell did, although he does not specify it.

Matthias Gottfried Purmann warns his readers not to use any oily medicines on a venomous wound after the eschar has begun to naturally separate. Instead he recommends his own

Photo: Jimmy Kreislauf

A Scorpion for the OIl (Euscorpius flavicaudis)

plaster to keep the wound open.

Rx. Empl. Stact. Crolles [Crollius’s Stictic Plaster, a compound used when healing wounds], manus Dei [Plaster of God’s Hands, containing a variety of healing ingredients], Diachil c[um]. Gum[mi] [Diachylon Plaster with gum] {of each, 7 ounces} Ceræ [wax] {1/2 pound} [Pine] Resin. {2 ounces} Terebinth. [turpentine] {1/2 ounce} Succin. [amber] {2 ounces} Oliban. [frankincense] Myrrh. Mastich. {of each, ½ ounce} Sal Armoniac {Ammonium Chloride] {1.5 drams} pulv Spinar. Viperar [powdered viper spine] {1 ounce} Malax c. s. q. [mix and cook with a sufficient quantity of] Ol Scorpion. M. f. ad Emplastrum [make into a plaster].13

This prescription is more complex than some of those suggested by the other authors, although it does contain several of the same ingredients including turpentine, wax and resin. Most interesting are the addition of powdered viper spine and oil of scorpions, two venomous creatures noted to cause these wounds. This is essentially the "hair of the dog that bit you" theory of venomous wound care which will be discussed in more detail in the section on medicines.

1 Stephen Bradwell, Helps For Suddain Accidents Endangering Life, 1633, p.40; 2 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 511; 3 Bradwell, p. 40; 4 Paré, p. 511; 5 Bradwell, p. 39-40; 6 Bradwell, p. 40-1; 7,8 Paré, p. 511; 9 See John Quincy, Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea, 1722, p. 280; 10 Paré, p. 511; 11 Bradwell, p. 41; 12 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 111; 13 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, 1706, p. 187

Venomous Animal Wound Treatment: Mechanical Poison Removal - Sucking Out Venom

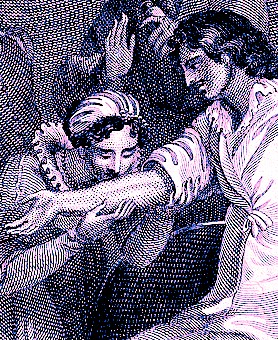

Two authors discuss sucking the venom out of wounds. Stephen Bradwell suggests this method for venomous wounds of the face in preference to cauterizing because it would not leave a large scar. His recommendation is is to "let somebody presently sucke the wound with his mouth: which ...is very good"1. Note that he does not say the surgeon should do this (and never suggests that he himself performed the process in his description.)

Engraving: Joseph Brown

Queen Eleanor Sucking Poison from Edward I's

Arm, From the Wellcome Collection

Bradwell gives a number of warnings to the person withdrawing the poison. "First, the sucker must take heed he have no sore, blister, nor rawnesse in any part of his mouth, tongue, gummes, throat, or lips; for then he endangereth himselfe, by sucking venomous matter into places prepared to entertaine the infection of it."2 Although this sounds like common sense, it is certainly something to take into consideration. "Secondly, before he sucke, he must wash his mouth, first three or foure times with white wine wherein Mithridate or old Andromachus Treacle [Venice Treacle] is dissolved; and after, with sallet-Oyle."3 The prophylactic use of mithridate and treacle, two well-known poison remedies during this period, again suggests Bradwell's concern for the person administering the cure. The salad dressing would contain olive oil and vinegar, both of which were reputed to have value in resisting poisons. Bradwell then advises the person sucking the poison out of the wound to be sure they spit everything out and avoid swallowing any of it. "Lastly when he hath sucked out all the venom; let him againe wash his mouth three or foure times with the like washing, as before he sucked. And to conclude, let him drinke a little draught of the same, to prevent all evill chances."4

Ambroise Paré also suggests this method, although he doesn't provide nearly as much detail. He simply says, "sucking [out the poison] is good, the mouth beeing first washed in wine where in some treacle is dissolved, and with oil, lest any thing should adhere thereto, for it will hinder it, if so bee the mouth bee no where ulcerated."5

1 Stephen Bradwell, Helps For Suddain Accidents Endangering Life, 1633, p. 41; 2 Bradwell, p. 41-2; 3,4 Bradwell, p. 42; 5 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 511

Venomous Animal Wound Treatment: Mechanical Poison Removal - Using Animals to Draw Poison

Perhaps the most unusual method for treating

Photo: Holger Krisp -

Horse Leech (Haemopis sanguisuga pferdeegel)

venomous wounds to modern readers was the use of live animals. The most straightforward example of this is the attach leeches to the wound. Both French surgeon Ambroise Paré and English physician Stephen Bradwell suggest the use of horse leeches to draw the poison from such injuries. Paré mentions it as a 'good' practice1, while Bradwell's recommendation is a bit more circumspect: "Some apply Horse leeches to the wound, if it be very small."2

Both also suggest a more bizarre treatment - rubbing the anus of a hen or female turkey on the wound. Paré specifies that they must be "hens or turkies that lay egs, for that such are opener behind."3

Both describe the process in a similar way. First, salt is rubbed on the animal's anus, "that they may gape the wider"4. The bird's beak is then to be held closed, "giving him [actually, her] breath but now and then, onely to keepe him [her] alive"5. The anus is then placed on the wound, "for thus it is

Photo: Ben Scicluna -

"Run that by me again?" Columbian Colored Hen

thought the poison drawn forth, and passeth into the bird by the fundament [anus]."6 Bradwell adds, "If one die, take another; and so continue till one of the creatures outlive the labour. Then may you bee sure the venom is cleane drawne out."7

If that sounds a bit drastic, Bradwell's final suggestion will really give pause. Here, the envenomed wound is to be scarified by making small incisions in and around it. The surgeon is then to "take a Pullet [hen] or a Pigeon, and divide it alive, and apply it (while it is full of lifes heat) upon the wounded and grieved place ...[so] that the vitall heate of that creature may draw the venom through the scarifications."8 The divided animal is to be bound to the would and left there "till it be even cold; and then apply another, and so another; till (by asswaging of all paines, and swelling without, as also by the quietnesse and quicknesse of the spirits within) the patient appeare freed from all poysonous offence."9 It seems that in order to make an omelette, the surgeons had to break a few eggs. (Sorry.) The last avian corpse being removed, garlic fried in butter or olive oil was to be placed on the wound "to make sure that no remainder of mischeife be behinde: for it is an excellent outward Medicine against all Stingings and Biting that are venomous."10

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 511; 2 Stephen Bradwell, Helps For Suddain Accidents Endangering Life, 1633, p. 43; 3,,4 Paré, p. 511; 5 Bradwell, p. 43; 6 Paré, p. 511; 7 Bradwell, p. 43; 8 Bradwell, p. 43-4; 9,10 Bradwell, p. 44